Abe leads march to a new constitution

Updated: 2014-07-04 08:09

By Cai Hong (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Reinterpretation of Japan's collective self-defense law flies in the face of public opinion

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has finally got his wish, even though some of his comrades in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party are rebelling and the public protesting.

On July 1, his cabinet decided to reinterpret Japan's constitution, allowing the country to exercise the right to collective self-defense.

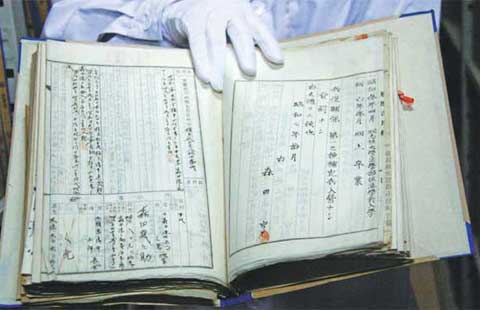

To be exact, it is a new interpretation of the supreme law's Article 9, which renounces war and prohibits Japan's use of force for purposes of engaging in collective self-defense actions and participating in United Nations collective security operations.

In the words of the Abe cabinet, the constitution allows Japan to use force at a minimum level when a country with which it has close ties comes under attack and there is a clear danger that threatens to fundamentally undermine the rights of the Japanese people.

The reinterpretation is being seen as a precedent for more stretching in the future. "The government could do whatever it wanted to, whenever it wanted to, and under ambiguous standards," warned an editorial in the Mainichi Shimbun. The Abe administration "has an obvious and expansive disrespect for the constitution and public opinion".

Members from different parties in Japan's local assemblies are mending fences and standing together against Abe's move.

By June 27, some 139 local councils across Japan had passed motions criticizing of the reinterpretation and submitted them to the lower house of Japan's parliament.

The municipal assembly in Aomori, in the north of Japan's main island, criticized the Abe cabinet for constitutional reinterpretation based on its own opinion. It said its decision is unacceptable because it is "an outrage that destroys the foundation of modern constitutionalism".

The Social Democratic Party and Japanese Communist Party, which are the minority in the assembly, were joined by the LDP members on the issue of collective self-defense.

The mutiny also took place in the ranks of the LDP. Its chapter from Gifu prefecture complained about Abe's haste and the lack of public discussion, in a rare dressing down that suggests even his own base of support is ambivalent.

Many Japanese, especially those in their senior years, are still haunted by the memories of World War II. This is just one of their reasons for supporting the policy of no more use of force abroad.

Haruo Yamamoto, 57, an LDP member, opposed the right to collective self-defense because of his father's war experiences. Yamamoto senior was enlisted by the Japanese imperial army as a kamikaze, or suicide pilot. He was on the waiting list for attacks on Japanese enemies' ships before the war ended.

Today, few Japanese elites want to remember the war and the tragedies it caused.

Abe is the first Japanese prime minister born after the war. His grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, was arrested as a Class A war criminal but escaped charges and went on to serve as prime minister.

Abe has inherited his grandfather's dream of rewriting Japan's constitution, which, in their eyes, was imposed by the United States.

Abe knows that the hurdles for constitutional revision are too high. The procedures laid out in the constitution require two-thirds approval in both houses of parliament and a majority of voters in a national referendum.

He is ramming through a reinterpretation of the constitution, circumventing the constitutional amendment procedure.

A Mainichi Shimbun poll on June 27-28 found that 58 percent of Japanese people opposed their government's move to lift a self-imposed ban on exercising the right to collective self-defense.

The approval rating for the Abe cabinet slipped from 54.7 percent in May to 52.1 percent in June, according the agency Kyodo News.

But the prime minister is not ready to heed public opinion.

A Japanese man in his 60s went so far as to set himself on fire in Tokyo's downtown on June 30 in protest at the Abe administration's resolve to allow Japan to exercise the right to collective self-defense.

No single Japanese soldier has been killed in battlefields overseas since the end of World War II, thanks to the post-war constitution.

Successive Japanese governments, including LDP-led cabinets, had interpreted the constitution in a way that collective self-defense was banned.

In an interview with Japan's Jiji Press agency, Kazutoshi Hando, an expert on the Showa era (1926-1989), warned that the reinterpretation will "completely nullify Article 9 of the constitution".

He forecast that Abe would seek to make a law to transform Japan's self-defense forces into a national military force. "That would be a point of no return. Japan would become a 'normal' country that is prepared for war," Hando said.

In a discussion organized by Japan's Social Democratic Party in Tokyo recently, Toru Hayano, a professor at the Tokyo-based Oberlin University, told a story that may illustrate the public concern in Japan.

The other day, Yoko Kitamura, a student at Oberlin University, asked in Hayano's class who Abe was.

"It is ironic that these young people may be sent by a person, they have no idea of to battlefields abroad," Hayano said.

The author is China Daily's Tokyo bureau chief. Contact the writer at caihong@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 07/04/2014 page11)

Today's Top News

Gambling costs World Cup fans their lives

US supports Ukraine's decision to suspend ceasefire

It's all about making a spectacle

China likely to see 7.5% growth in second quarter

Palace Museum feeling the squeeze of visitors

Myanmar pagoda replica given to China

US sends 300 more troops to Iraq over concerns

Hong Kong at the crossroads

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|