The revival of Chinese tea

Updated: 2014-05-02 07:49

By David Gosset (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

It's time the beverage, eulogized in art and literature, regained its pride of place

Ubiquitous yet enveloped by a flavor of gentle mystery, tea is one of China's most extraordinary gifts to mankind. Its trade determined the fate of some of the earliest multinational companies such as the East India Company. It is a part, with the 1773 Boston Tea Party or the 19th century Sino-British wars, of the world's political history.

But, above all, it stands as a living symbol of civilization. From the materiality of its green leaves to the infinite nuances of its warm perfumes it is an endless conversation between nature and culture.

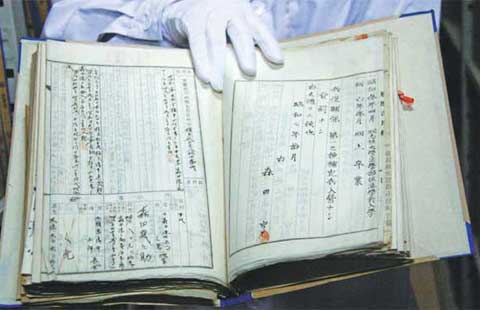

Its origin goes back to the dawn of China's history. The 10 chapters of the Classic of Tea, the first monograph on the evergreen plant, were composed by Lu Yu at the end of the 8th century, but tea drinking was customary during the Shang Dynasty (1600 BC-1046 BC) when the Camellia sinensis was valued for its medicinal properties, a discovery often attributed to the legendary ruler Shennong, the "Divine Farmer".

What evolved into the world's most widely-consumed beverage after water has been a theme of Chinese literature and art for centuries. Tang Dynasty (618-907) poet Lu Tong shared his tea sensations in the Seven Bowls of Tea; Song Dynasty (960-1279) Confucian thinker Zhu Xi, also known by his pseudonym "Tea Immortal", imagined Tea Stove while boating on the Nine Bends Creek in the Wuyi Mountain; and Fan Zeng, born in 1938, painted Appreciation of Tea.

Following its arrival on the European continent in the 17th century, the drink became also "the Muse's friend" for Edmund Waller (1606-1687) and Peter Anthony Motteux (1663-1718) composed A Poem In Praise of Tea (1701) in which he evokes his passion for the "crystal stream":

Tea, whose fame should over all plants be raised

None, says the God, shall with that tree compare

Health, Vigor, Pleasure bloom for ever there

Sense for the learned and beauty for the fair.

Silk, porcelain or jade have adorned Chinese interior spaces for millennia but tea has marked the Middle Kingdom even more profoundly; it both nourished the bodies and nurtured the minds. Despite these vital connections, one often associates tea culture today with Japan, a phenomenon explained by the relative decline of the Chinese power in the 19th century but which is also the effect of a Japanese effort to articulate a tea narrative eloquently presented to the Western public.

Okakura Kakuzo, in The Book of Tea (1906), proudly affirmed: "Tea began as a medicine and grew into a beverage The 15th century saw Japan ennoble it into a religion of aestheticism - teaism." Kakuzo codified an attractive modern discourse and some Japanese tea masters - like Sen Soshitsu XV and Sen Soshitsu XVI of the Urasenke family for example - maintained the tradition, explained and exported teaism to the world in one of Japan's manifestations of soft power.

The result is striking. While Japan is only the world's 10th-biggest tea producer - in 2010 Argentina produced more - the tea ceremonies evoke the temples and gardens of Kyoto than the shores of Hangzhou's West Lake.

But as the reinterpretation of the Chinese tea culture is one of the elements of the Chinese renaissance, the perception of the Chinese green leaves might enter a new phase in the 21st century.

At least three conditions are needed for China's liquid gold to regain its historical prestige. First, the country is the world's top tea producer but its highly fragmented domestic market where 70,000 producers compete is in need of consolidation. In Yunnan province, famous for its tea farms, only 20 tea companies show yearly revenue of at least 100 million yuan ($16 million), a situation which explains the remark often heard in the Chinese tea business circles: "70,000 equal one Lipton!"

Second, the reinvention of Chinese tea and its global projection will develop in tandem with the maturity and sophistication of the domestic market. The opening of elegant tea houses across the country is an important step for the transformation of the industry but in fine dining restaurants, the tea list should be as complete as the wine list. White, green, Oolong, black or Pu'er teas have to be presented, at the very least, with the exact zones of production, time of harvest and the name of the producers. During the Tang Dynasty the connoisseurs, always in quest of superior refinement, expected the specification of the different waters used for brewing tea.

Third, a long-term strategy of branding has to be formulated. The worldwide success of the French wines of Champagne has its source in the 19th century marketing genius of Laurent-Perrier or Veuve Clicquot. In the contemporary universe of Chinese tea, only a very small group is aware of the necessity to have a long-term vision focused on uncompromising quality and style. Among that pioneering few, the ideals of Wu Rongshan, whose exquisite Anxi Tieguanyin, the Floral Fragrance No 1, offers the most delicate sensations, could become a new point of reference.

It is Wu who created a special tea named "The Perpetual Friendship" to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Sino-French diplomatic relations, and on March 27 this tea was presented, in a highly significant gesture, to French President Francois Hollande and Chinese President Xi Jinping in Paris.

Wu also established Fuzhou's Salon des cultures, a new concept of tea house where people gather around cups of tea to discuss art, fashion, design and aesthetics, with the aim to spark "creativi-teas".

At a time of mistrust, misunderstanding and ecological disorder, the Tao of tea is a transformative path toward harmony. As Lu Tong wrote more than 10 centuries ago, at the fifth cup, our "flesh and bones will be purified"; after the sixth, "one communicates with the Immortals".

The author is director of the Academia Sinica Europaea at China Europe International Business School, Shanghai, Beijing & Accra; and founder of the Euro-China Forum. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily European Weekly 05/02/2014 page12)

Today's Top News

EU: No armed intervention in Ukraine

Chinese premier visits Nigeria

Court to rule on Yingluck in Thailand

Travellers to Malaysia drop

Chinese to US grad schools drop

Ukraine moves special forces to Odessa

Slovenian PM resigns

Disclosure of military secrets becoming bigger risk

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|