The language instinct

Updated: 2014-05-02 07:50

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

|

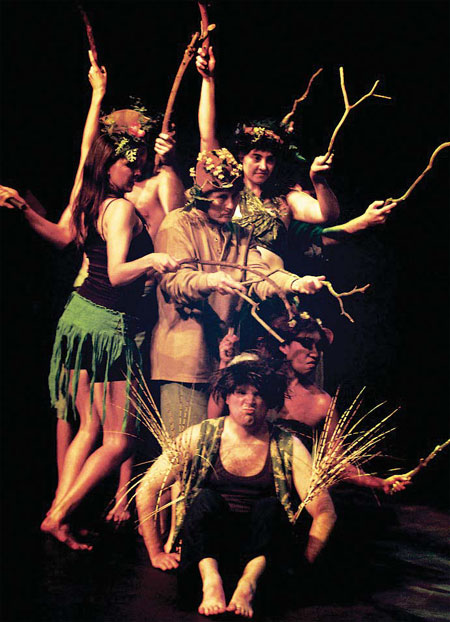

Touring productions such as A Midsummer Night's Dream will have a subtle impact on Chinese perceptions of the Bard. Provided to China Daily |

Keeping the literary legacy alive

Chinese people with no knowledge of the English language found initial access to the Bard through Charles and Mary Lamb's Tales from Shakespeare.

In 1903, 10 of the stories appeared in a Chinese version re-titled Strange Tales from Overseas. The translator was Lin Shu (1852-1924), who knew no foreign languages but, with the cooperation of bilingual talents, was able to wield wide influence by producing top-rated Chinese translations of many Western literary classics. The following year, Lin completed the entire collection and republished it under the title The Mysterious Stories of the English Poet. Two years on, in 1906, Lin tackled five of the history plays from the root source, but again as freeform fiction rather than plays for staging.

Lin used a style of written Chinese that had been accepted by men of letters down the centuries, but sounded archaic to people on the street. It took a playwright to take up the gauntlet of translating Shakespeare as it is intended that is, as a language spoken by actors in a theater. In 1921, Tian Han (1898-1968), who later emerged as a major figure in Chinese theater and film, launched an ambitious project to translate 10 of the Bard's works, but only managed to finish Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet. These were the first complete Chinese translations and employed a dramatic form similar to the original.

Since then, Shakespeare has been translated and retranslated each version with its own merits and foibles. According to Lu Gusun, a professor of English literature in Shanghai, as many as three Chinese versions of Hamlet appeared before 1949, and at least five more were published afterward, two of them in verse form.

English and Chinese are very different languages, so many of the problems that arise are common to all literary translations. However, there are issues unique to Shakespeare, the most prominent being poetry versus prose. Many Chinese translators chose prose mainly because they wanted to better preserve the flow of the sentences, which tend to go across lines in English. For rhyming couplets, they usually stuck to the verse form. Maintaining the original structure of the verse, on the other hand, dramatically increases the level of difficulty of simultaneously retaining lucidity and loyalty to the original meaning.

Dramatic flair

Another complication lies in the vast vocabulary employed by Shakespeare. The Chinese translator has to possess a similar word horde in the Chinese language, or more accurately, he or she had better be armed with an even larger reserve to find the best equivalent for a certain expression. That's why the best translators tend to be those from the older generation, because they grew up at a time when Chinese classics were drummed into them from an early age and both the archaic written and the new vernacular styles were in use.

The best translators also need dramatic flair. They have to render each character in a linguistic style befitting that person. The way a king speaks should be distinct from that of a court jester. Overall, Shakespeare in Chinese translations could come over as highly literary and even pompous, with never-ending sentences and modifiers heaped upon modifiers, useful for putting the Bard on a pedestal, but detrimental to bringing him closer to the public. Because most translations were made by those who study Shakespeare rather than those who present him on a stage, theatrical adaptors and directors sometimes have to tweak existing translations to make the lines more colloquial.

Then there is the stylistic quagmire. Because of cultural differences, the early versions toned down the raunchy content by expunging references to sexual organs and other "unsavory" subjects. This is more a result of a different mentality, because Chinese classics may also contain such descriptions, but somehow people familiar with the Bard's name but not his texts often assume he was a pristine, preaching icon, or would like to shape him in this moral configuration.

Some of Shakespeare's lines are open to debate. That ambiguity is hard to reproduce in a different language. You have to pick one of the interpretations. Moreover, it takes a literary genius to even attempt puns and jokes in a totally different language with dramatic constraints. I still remember my joyous laughter when I first came across one example in A Midsummer Night's Dream when Quince uses "paramour" when he means "paragon". I read the Chinese first and then searched for the original. The resemblance, in effect, is uncanny.

Notable translators

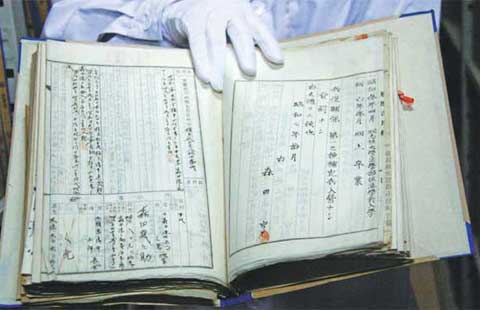

The translator of that pun was Zhu Shenghao (1911-44). He was a titan among those who made Shakespeare accessible to a quarter of the world's population. Zhu's life story is worthy of a Hollywood biopic. In 1935, he launched a personal undertaking to translate all of Shakespeare's plays in two years a plan derailed by poverty, illness and the Japanese invasion of China.

In 1936, Japanese planes bombed Shanghai, destroying many copies of the comedies Zhu had already translated. In 1941, when Japanese soldiers marched into the newsroom where Zhu worked, he again lost many of the manuscripts he had been working on.

By the time he died of tuberculosis at the tender age of 32, Zhu had translated 31 (and a half!) of the plays. Of those, 27 were published posthumously in 1947 in three volumes that form the backbone of later complete editions.

Taiwan's World Publishing House came out with The Complete Plays of Shakespeare in 1957. Zhu's 27 posthumously published translations were supplemented by Yu Erchang's 10 history plays. In 1978, the Beijing-based People's Literature Press published The Complete Works of Shakespeare, using Zhu's 31 plays as the foundation, meticulously edited. The other works, including all of the poems, were translated by a number of distinguished scholars.

Despite being in prose, Zhu's translations stand out for their exceedingly high quality. Considering his age, his mastery of both English and Chinese can only be described as genius. His version of the Bard's works is widely acclaimed as the one that best preserves the essence of Shakespeare.

Compared with Zhu, Liang Shiqiu (1902-87) had the advantages of longevity and name recognition. Liang is the only Chinese so far who has singlehandedly translated every piece Shakespeare is known to have written. He started in 1931 at the urging of Hu Shi, a leader of the "New Literature" movement. By the time he completed this mammoth project, in 1967, Liang had long established himself as a prominent essayist in his own right.

Because Liang moved to Taiwan with the Kuomintang, his versions were not published in the mainland until 1996. He used an approach similar to Zhu's, namely, prose for blank verse in the original.

(China Daily European Weekly 05/02/2014 page25)

Today's Top News

EU: No armed intervention in Ukraine

Chinese premier visits Nigeria

Court to rule on Yingluck in Thailand

Travellers to Malaysia drop

Chinese to US grad schools drop

Ukraine moves special forces to Odessa

Slovenian PM resigns

Disclosure of military secrets becoming bigger risk

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|