A stitch according to the times

Updated: 2014-04-25 07:28

By Joseph Catanzaro and Cai Muyuan (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

|

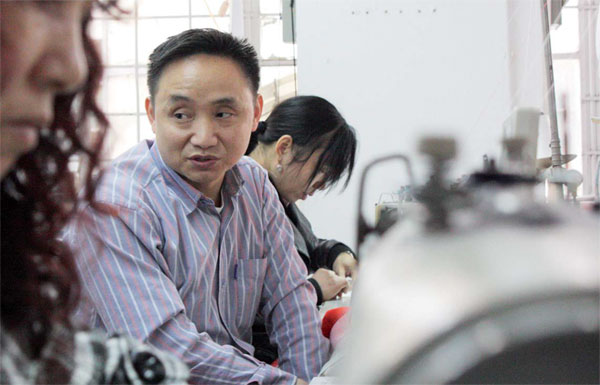

Lu Keqin, a sewing workshop owner, says he is struggling to survive as overseas orders have fallen sharply. Photos by Joseph Catanzaro / China Daily |

|

Workers are busy making garments in Lu's workshop. |

The tailor

The elderly women sit on a step by the side of the road and sew by hand. Their weathered faces are maps of smile lines and crow's feet, their hands and chatter lightning quick.

A small mountain of denim jackets teeters precariously in front of them, piled up right out on the street. The hole-in-the-wall workshop behind them is crammed with sewing machines and workers and material.

On either side of the narrow thoroughfare where the women stitch, big old factories tower like rust and ruin reefs.

No one seems to remember the original purpose for the long, multi-level structures. Every nook and cranny of both buildings is now occupied by tiny factories and workshops, organic growth on the skeleton of a failed big business, teeming pockets of industry separated by thrown-up partitions.

In one of those small spaces, Lu Keqin sits at a sewing machine with about half a dozen others, deftly making women's business shirts. The 44-year-old has been at it since 8 am, and he won't finish until midnight. It's a work routine he follows every day, seven days a week.

Unlike the others, Lu is not an average sewing workshop employee, although that is how he started out. He's the boss, this is his business, and it's struggling.

A few seats up from Lu, an older woman sits and stares at a faded bit of graffiti on her machine while she works, humming to herself.

It's a love heart and some initials.

"I don't know who put that there," she says. "It was from before my time."

Across from her, Zhao Shuang, 30, works in silence.

Her fingers deftly run the beginnings of a lacy top under the insistent stab of the needle, her tiny feet work the pedals.

A migrant worker from Hubei province, Zhao came to Shenzhen about a decade ago chasing a higher pay packet in the city. The mother of one says wages and conditions have improved dramatically in the past few years. She makes about 4,000 to 5000 yuan ($641 to $801 , 464 to 580 euros) per month, on par with the average wage for a university graduate in Beijing.

It's good news for her family back home.

Even though she only gets to see them twice a year, she says she and her construction-worker husband are saving to send their 5-year-old daughter to university when she grows up.

Lu doesn't resent paying his workers more, but it is one part of the multifaceted problem facing his business.

Back in 2008, Lu owned a 1,000-square-meter factory and had 70 employees. For a migrant worker from Jiangsu province, the enterprise was the culmination of years of hard work at a sewing machine, of scrimping and saving.

Business was booming, foreign orders from Europe and the United States were rolling in.

"I was making about 1 million yuan a year," he says.

In 2009, things changed after the global financial crisis. Overseas orders suddenly slowed down, then stopped almost entirely.

"It's a manufacturing transformation," Lu says. "More and more orders go to Southeast Asia where they work hard and are paid less. Other orders are going to inland China where the price is also lower."

Last year, Lu says he made no profit at all. He now rents this 200 sq m workspace and has a roster of about six employees working the machines.

He concedes the ailing state of his business, and the relatively improved lot for his employees, represent a changing China.

All is not lost, Lu says, because he's changing with it.

Back in China's textile industry heyday, Lu made silk business shirts for American professionals and nightgowns and evening wear for women in Europe.

The textile industry, once the economic fabric of many regions in China, is now fraying.

Lu is stitching his business back together by focusing on making high-end, quality products for domestic buyers. That he's able to do this at all speaks of the rising demand in the Chinese consumer market.

"Each of my workers makes about 200 items per day if it's simple (clothing)," he says. "If it's a harder piece, they maybe only make 10 or 20 items."

Lu is blunt about the nature of the work, but resents the sweatshop stereotype.

"Our workers work long hours," he says. "They are busy and it's hard work. But the situation for workers is better than it was a few years ago. They make more money.

"One reason for that is the law. Back in the 1990s, there wasn't much to protect workers' rights and they got paid less. Also, now more workers know what their rights are. They demand more, and they want benefits."

Lu says the more clothing workers make, the more they get paid. Each worker chooses how many hours they want to put in.

"When business is good and there's lots of work, they can make 10,000 yuan per month," he says. "Some of them don't take lunch or don't take days off. They choose their hours, it's very flexible."

And no one works longer hours at a machine than him.

"I don't have time to have fun," he says. "I start work at 8 am and go until midnight. I go to sleep at 2 am, seven days a week. I never take weekends off."

Lu's wife sells cosmetics. They have settled in Shenzhen, and now consider it home. Their 6-year-old daughter is the joy of Lu's life.

She is the only reason why he breaks his demanding, self-imposed work schedule.

"I never miss my daughter's dance recitals," he says. "I watch every one."

From basic worker to business owner, Lu's progression is a snapshot of the changing lot for many Chinese. Like Zhao, he doesn't want his child to follow him into his profession.

"I don't want that," he says. "I want my girl to go to college, I want her to be a doctor or a teacher. But in the end, I'll support her decision about what she wants to do in life."

At her sewing machine, Zhao says she misses her husband and her little girl. She hopes that she can see them more than twice a year. But right now, she needs to stay in Shenzhen, where she can earn double what she can make back in her home province.

She says what drives her is the same thing motivating all Chinese workers.

"Chinese people do everything for their children, and I'm no exception.

"My parents are farmers. It's tiring work and you can't make much money. My family mostly grows food to eat, not to sell. I want to make more money in the future for my daughter's education. I want the best for her."

Zhou says she doesn't think much about where her cloth creations go, or who will wear them. Neither does Lu.

The clothes they put together might be worn by hip, young professionals, but that's not who they say they are making them for.

They turn back to their sewing machines, piecing together brighter futures for their children, one stitch at a time.

(China Daily European Weekly 04/25/2014 page12)

Today's Top News

EU: No armed intervention in Ukraine

Chinese premier visits Nigeria

Court to rule on Yingluck in Thailand

Travellers to Malaysia drop

Chinese to US grad schools drop

Ukraine moves special forces to Odessa

Slovenian PM resigns

Disclosure of military secrets becoming bigger risk

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|