Power shift will fuel IMF restructuring

Updated: 2014-04-18 07:53

By Giles Chance (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Washington cannot stand in the way of changes to rules that were set 70 years ago

As China has started to fulfill its economic potential of the past 20 years, it has become one of the key global economic players. Its first big global contribution occurred as an exporter of manufactured products to developed countries. From the mid-1990s, the impact of China's huge, low-cost labor force provided global consumers with a wide range of everyday items, at much lower prices. From early this century, China's global impact increased, as its demand for commodities to build its infrastructure drove large increases in raw material prices. Higher commodity prices made an enormous difference to the external finances and wealth of many emerging countries, from Chile in South America, to Zaire in southern Africa. After the financial crisis in 2008, China's huge economic stimulus plan became the main economic factor preventing a global depression.

Led by China, the emerging world has come to play an ever larger role in the world economy.

It is unsurprising then that the International Monetary Fund predicts that by 2020 the emerging countries, of which China is easily the largest, will contribute almost the same to global growth as the advanced global economies, 42 percent of global GDP against 44 percent. The comparison is striking if GDP is adjusted for widely different price levels. Using purchasing power parity, in 2020 the emerging world will account for 55 percent of global GDP, while the advanced economies will contribute only 34 percent.

But the influence of the emerging world on global governance will have to increase substantially if international organizations like the IMF and the G7, now dominated by the advanced nations, are not to subside into irrelevance, says a report issued last month by Jim O'Neill, former chief economist of Goldman Sachs, and Alessio Terzi, of the Breughel Institute in Brussels.

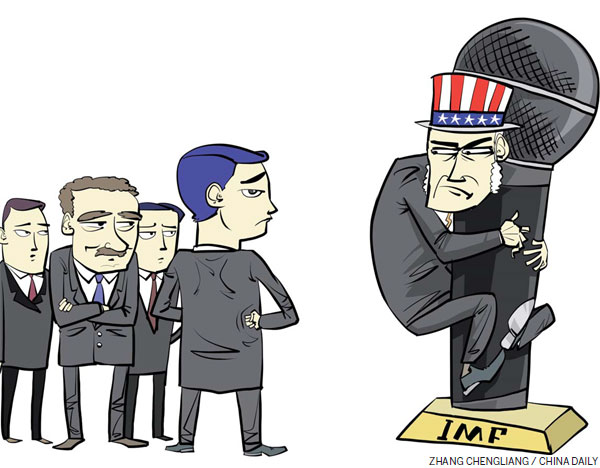

So it was a shock when in January and again in March, the US Congress did not support a 6 percent increase in the voting power at the IMF of emerging countries, along with a doubling of the IMF's capital, which the IMF board authorized in 2010. This was even though the proposed change would not alter the US's position in terms of votes, because all votes gained by the emerging countries would be taken from Europe, which under the proposed changes would lose representation in the IMF in line with its declining economic significance.

When the 188 member countries of the IMF gathered in Washington from April 11 to 13 to hold its spring meeting, the question was: Will the US be able, on its own, to prevent change at the IMF? Or will change happen anyway, despite the US? Has a dramatic power shift in global affairs begun?

The idea of forming the IMF immediately after World War II came from the British economist John Maynard Keynes. His view was that the IMF should be a global organization that would co-ordinate growth by managing the international monetary framework. But this idea ran counter to the wish by the Americans to have the world economy run from Washington by the US Government, with the US dollar as the world currency. Instead, the IMF has become the lender of last resort to troubled economies around the world and a vital actor in economic crises, from Asia in 1997-98 to Europe in 2010-13. It remains a vital instrument of global governance, perhaps the one, with its focus on global money and global growth, to which China pays the most attention.

Today the IMF is based in Washington and is staffed with economists from around the world, but the US still controls it with an effective veto, holding 16.75 percent of the voting power, with an 85 percent voting majority required to approve important proposals and changes. The US joined Britain as a cornerstone founder in 1945. As a result, important proposals requiring additional commitments from the US to the IMF have to be passed by the US Congress. The IMF voting structure, dating back 70 years, allows a fundamental change agreed on by all the IMF members except the US to be denied by a relatively small number of conservative US politicians. Yet, of course, the world is very different to what it was in 1945. Shouldn't the IMF's structure reflect that changed reality?

A recent article by James Roberts, an economist working at the right-wing US institution The Heritage Foundation, underlines the reasons for conservative Republicans in Congress to withhold their support for the IMF changes. He argues that the proposals would turn the 24-person executive committee of the IMF into an elected body. At present the US has the right to appoint one member of this powerful committee. If the committee was an elected one, it is possible the US would not have any representation in the top echelons. In addition, the US now controls the allocation of $63 billion of extra funds available to the IMF for lending in a crisis, because it contributed $18 billion to this pool. The proposed change would give authority of this supplemental lending to the executive board.

The US is scared of losing important influence over the IMF, a powerful and influential global organization. Roberts suggests that Congress should send the reform proposal back to the IMF to be amended. He does not even think that change is necessary, because countries should look after their own affairs, and money from the IMF can make things worse for poor countries by removing the need to take hard, but beneficial economic decisions.

A letter to the Financial Times of London on April 10 from two influential US economists, both former senior US Treasury officials, recommends that the IMF go ahead with the changes, without the US. At the G20 meeting held at the same time as the IMF meeting, the members decided to give the US Congress until the end of 2014 to approve the change. Otherwise the IMF will have to go forward without the US. If Washington continues to hold out, its refusal to accept inevitable change could start a slide in the global authority of the US, as the IMF restructures itself to reduce US influence.

China is a committed partner of the US, but is also the largest emerging economy and stands to become the IMF's third-largest voting shareholder from the change in voting power, after the US and Japan, overtaking Germany and founder members France and Britain. But whatever the outcome of this particular affair, there is no doubt that the huge changes in the global economy will be reflected in institutions like the IMF and the G7, which take the important global decisions. In a decade, Europe's participation in the G7 may have shrunk to one or two countries, while China and India may both have become members. Whatever the US does, big changes in the institutions that govern the globe are on the way.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily European Weekly 04/18/2014 page13)

Today's Top News

EU hopes to strengthen climate co-op with China

64 dead in Korean ferry sinking

Nuclear plants to get the nod

No naval meet with Japan

Putin makes overture to incoming NATO chief

China on frontlines of cyber threat

China raises alert against cancer

William, Kate visit Australian air force base

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|