Staying till death do us apart

Updated: 2014-04-11 08:08

By Luo Wangshu and Zhou Wenting (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

|

A man visits the grave of a family member at Beijing Expatriates Cemetery, which used to host many foreigners who died in China but now serves mostly Chinese. Wang Jing / China Daily |

While expats are coming to China in ever-greater numbers for work, only a few plan and are able to spend eternity here

Fallen leaves return to their roots, according to an old Chinese saying, referring to most people's wish to be buried in their place of origin.

Regardless of how far one may have wandered, it's much easier to achieve that wish these days than, say, a century ago because of the vast improvements in transport and logistics.

Years ago, China had cemeteries that were exclusively for foreigners, mainly in cities that had foreign concessions, areas ceded by China and administered by foreign powers.

But that's history. In recent years, China has restricted the burial of foreigners. Simultaneously, cremation has become the more common option, and international shipping of bodies has become more practical.

Cemeteries that were formerly for foreigners only are now open to Chinese people who wish to find eternal rest in an international community.

Beijing Expatriates Cemetery, formerly the capital's largest cemetery for expatriates only, has interred nearly 5,000 Chinese since 1996.

Shanghai Wanguo Cemetery, which holds the graves of more than 600 foreigners, is now part of the Soong Ching-ling Mausoleum Park, where Soong Ching-ling, whose husband Dr Sun Yat-sen was the founding father of the first republic of China, lies buried with other notable Chinese.

"It is nearly impossible for a foreigner who has no relative in China to have a body buried here now," says Wilfried Verbruggen, who operates a body repatriation service in Beijing.

In 2008, the Ministry of Civil Affairs released a regulation on the management of foreigners' funerals and interment that largely banned their being buried in China.

But there are exceptions.

Xiao Chenglong, deputy director of a center that studies funeral development and interment, says, "It looks like more foreigners want to be buried in China.

"Some of them may have strong emotional ties to the country or make a great contribution to China. We should give them access if that is what they hope for," says Xiao, of the 101 Research Institute under the Ministry of Civil Affairs.

Shanghai Wanguo Cemetery accepts applications for the burial of foreigners, but the criteria are high, says Li Chuntao, director of cultural relics preservation of the Soong Ching-ling Mausoleum's administration.

"The people buried here have to have made exceptional contributions to society. The applications must be approved by the municipal government," he says.

As cremation becomes more the norm and logistics improve, foreigners increasingly choose to have their ashes or bodies shipped home.

The National Funeral Association has set up a nationwide network for international body repatriation and transports about 1,800 remains a year.

According to the Ministry of Civil Affairs, the number is six times the average in the early 1990s.

Verbruggen, who has been involved with body repatriation for nearly eight years, says his business is increasing by 15 to 20 percent annually. On a personal note, he says he would like to return home after death.

"My wish is that my body will be buried in Belgium, my native country; very simple, and I hope my family and friends will make it into a party! It's no big deal, no need for grief. We are born to die."

The cemeteries for foreigners that have survived over the past century serve as witnesses to China's transformation, testimony to history and a bond of international friendship.

After China signed a treaty with Great Britain in 1842, the ports of five cities, including Shanghai and Fuzhou, were opened to Western merchants. Foreigners moved there with their families. When some countries were granted concessions, they built cemeteries in them for foreigners.

In Shanghai, Huaihai Park and Jing'an Park used to be cemeteries in the International Settlement, and more than 4,300 people were buried there, 93 percent of them foreigners.

Beijing had cemeteries for the French, British, Russians, Japanese and Portuguese in 1929, as well as an international cemetery.

A number of famous foreigners - such as Shafick George Hatem (1910-88), a doctor from the United States who became a Chinese citizen - are buried in Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery.

Edgar Snow (1905-72), a US journalist and the author of Red Star over China, is buried on the campus of Peking University.

The capital also held tombs of missionaries, such as Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) and Johann Adam Schall von Bell (1592-1666). But most of these have been removed in the waves of urban development over the past decades.

To clear cemeteries and tombs from the city center for municipal development, the Beijing government established an expats' cemetery in the northeast outskirts of the city in 1952. It is now known as Beijing Expatriate Cemetery, funeral and burial expert Zhou Ji-ping wrote in his book History of Beijing Funeral and Interment.

Foreigners' remains were moved from old gravesites to the new cemetery or returned to their native countries.

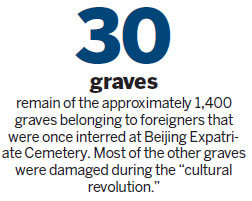

At one time, about 1,400 foreigners lay buried at Beijing Expatriate Cemetery, but now there are only about 30 most of the other graves were damaged during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76).

Shanghai Wanguo Cemetery, on Hongqiao Road in Changning district, holds the graves of more than 600 foreigners from 26 Western and Asian countries.

A business couple from Zhejiang province bought the 37,000-square-meter tract of land in 1917 and built the cemetery for locals and foreigners without restrictions of nationality, race or family background.

Nearly 5,000 Chinese and prominent foreigners were buried in coffins, as cremation had not become widely accepted, and many of them were notable figures from cultural, artistic, political or economic circles.

But all of the graves were destroyed during the "cultural revolution" except the two for the parents of Soong Ching-ling.

"Some foreigners' graves escaped being destroyed by being moved out before the 'cultural revolution'," Li says.

After Soong died in 1981 and was buried there, the cemetery became Soong Ching-ling Mausoleum in 1984, and the Wanguo Cemetery, which existed before the "cultural revolution", became part of it. All foreigners' graves in the city were moved to the cemetery.

"These people include sailors, chefs, photographers, bank clerks, and any other identity and profession you can imagine. They would all be over 100 years old if they were alive," says Li, of the mausoleum's administration.

The graves, now totaling nearly 600, are marked by small stone squares lined up in the grass with names engraved on them. Some are engraved only with Chinese names, while others have the Chinese names and abbreviations of the people's names in their mother tongues.

"The engravings were based on the limited data available when the tombs were moved, and that also makes it hard for us to help descendants of these people to find their ancestors' graves," Li says.

A man in his 40s once came to inquire about his great-grandfather's grave, says a woman named Qin in the administrative office of the mausoleum.

"We were unable to find who he was looking for because he couldn't clarify the ancestor's identity and our information was incomplete," Qin says.

But these searches are not always in vain.

The grandchild of a German family in Shanghai came to the cemetery three years ago and finally found the tombs of his grandmother and one of his uncles. Qin learned some stories about the German family from him.

"He told us his grandfather moved with his wife and son to Shanghai in the 1900s and worked in a bank. They had another son in Shanghai. The older son opened a clinic and lived until the 1940s," she says.

Every year, Li says, three to five people ask for help in finding their ancestors.

In December, they found the graves of four Britons who were among the first British troops sent to defend the international settlement in Shanghai during Japan's invasion of China in 1937, Li says.

"The men were members of the Royal Ulster Rifles, and a senior officer from HMS Daring laid a wreath at the soldiers' graves," he says.

Few descendants of these foreigners come to visit, Li says.

Cemetery workers keep the graves tidy, and on special days, such as Tomb Sweeping Day April 5, this year flowers are placed on each grave.

"A memorial hall for these people is in the works to commemorate their dedication," Li says.

Contact the writers at luowangshu@chinadaily.com.cn and zhouwenting@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Shanghai Wanguo Cemetery, on Hongqiao Road in Changning district, holds the graves of more than 600 foreigners from 26 Western and Asian countries and many Chinese too. Gao Erqiang / China Daily |

(China Daily European Weekly 04/11/2014 page24)

Today's Top News

Violence may escalate tensions with Moscow

After Crimea won, Putin tries not to lose Ukraine

Foreign investment law to be revised

Recorder may have gone silent

Enemies share eternity together

Response to tainted water raises concerns

Anti-graft rules made by local governments

Crucial Snowden questions loom over Pulitzers

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|