Companies in the East 'think long term'

Updated: 2014-03-28 08:45

By Cecily Liu (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

|

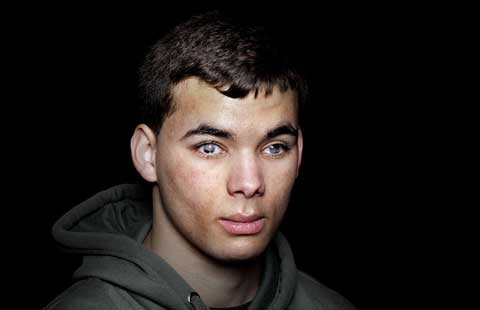

Daniel Pinto, co-founder and CEO of Stanhope Capital, says Chinese executives are able to make decisions that promote the long-term growth of their companies. Provided to China Daily |

Western bosses have lost their touch in driving entrepreneurship, says investment expert

The West has lost the spirit of entrepreneurial capitalism and needs to relearn lessons from the East, says Daniel Pinto, co-founder and CEO of investment firm Stanhope Capital.

Pinto, 47, says the long-term thinking of some executives from the East is driving their companies to become global industrial leaders, as more executives in the West are becoming "administrators-in-chief" because of the inefficient way in which incentives work.

China, for example, has an economy fuelled by state-owned enterprises that focus on long-term investment, and a private sector led by CEOs who also take a long-term view, as they are mostly founders of their businesses, or the founder's family members, Pinto says.

He cites the carmaker Geely and the computer-maker Lenovo, both of whose founders, Li Shufu and Liu Chuanzhi, remain key driving forces in their firms.

Unlike their Western counterparts, who make short-term decisions to please analysts and shareholders, Chinese executives like Li and Liu are able to make decisions that promote the long-term growth of their companies, Pinto says.

"We have killed the entrepreneurial drive of the West. At the very same time the East has done the exact opposite," Pinto says, pointing out the irony that capitalism was invented in the West.

Western entrepreneurs used to be captains of their industries when their companies were owner-controlled, he says, but they have now become short-term thinkers, no longer investing in research and development or capital projects.

The problem lies in the incentive system, Pinto says. CEOs of Western-listed companies are often paid bonuses that are linked to their companies' share prices over three years or less, which he says is outrageous, considering it takes about five years to build a car production line and 10-15 years to develop a new drug.

Investors also take a short-term approach, particularly fund managers, who must demonstrate good returns to investors to maintain their confidence at frequent intervals, he says. This further encourages CEOs to aim for short-term results.

Having seen the problems Western companies have, Pinto warns Chinese companies not to copy them. Going public has become so popular among small Chinese businesses that stock exchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen can typically have prospective IPO candidates waiting in line for several years, and Pinto cautions against the trend.

"They should think twice. When you go public, you have currency as a weapon to grow more rapidly. But the danger is that you have less flexibility as a shareholder; you take longer to make decisions. All sorts of people dream about the public market and don't see the other side of the coin."

Pinto says that he does not agree with the view of some economists that all businesses should go public once they reach a certain size. He says a good example is the British construction equipment manufacturer JCB, whose owner Anthony Bamford once considered taking the company public, but decided not to.

The company was badly hit by the financial crisis, as sales collapsed from 72,000 machines in 2007 to 36,000 in 2009. Such a spectacular fall would generally prompt a listed company to cut investment, but JCB kept up its production capacity investment, which allowed it to stay prepared for the recovery in more recent years.

For this reason, Pinto says, Chinese companies should not irrationally rush into listings without first understanding the implications. Chinese companies venturing into overseas markets should not succumb to pressure from financial commentators to go public just to increase transparency.

The argument that China's largest telecommunications company Huawei should go public to improve transparency has attracted increasing attention in recent years, but Pinto believes it is "a mistake to respond to these concerns".

"They are saying, if you are bidding for contracts in the public sector, and if some Western governments become clients of yours, we need to know who you are as a firm."

Such demands are irrelevant, he says, because Western governments that buy products and services from Chinese companies like Huawei should ask for the information they require, and the Chinese company can supply this information if they want to.

"They don't have to go public to supply it."

While pointing to the shortfalls of listing, Pinto says there are many advantages to being a public company, a model that may suit some Chinese companies. But Chinese companies' founders or their families should retain a strong influence in the company after the IPO, he says.

This is crucial because many of China's first-generation entrepreneurs are reaching retirement age and can no longer firmly guide their businesses through future challenges, Pinto says.

"You have to define the role of the family in the business. If the children of the founder cannot become the new CEO, then they can still maintain a tremendous amount of influence on the board. In the day-to-day decision-making process, they have to give the CEO a sense that they don't care so much about quarterly earnings, but the long term."

Pinto cites the Italian carmaker Fiat, which belongs to the Agnelli family. Although current CEO Sergio Marchionne is not a member of the family, John Elkann, great-great-grandson of Fiat's founder Giovanni Agnelli, is the chairman.

Pinto believes Chinese companies could learn from firms like Fiat on how to maintain this family influence. When there is a younger-generation family member who is willing and able to take on the business, he or she should be given training on how to become the leader.

On the other hand, if no younger family member can take on the role and outside professionals are taken on as managers, the family should retain its influence, perhaps by becoming a large minority shareholder.

In Pinto's analysis, the West's problems started in recent decades when many former family-owned businesses went public and diluted their shares.

In Britain many family business owners took their businesses public in the 1970s under the pressure of high inflation and high taxes. Pension funds, insurance companies and fund managers were the three dominant types of shareholders in Western-listed companies until the 1990s, when the percentage share holding by fund managers rapidly increased.

This fund-manager growth had dire consequences because fund managers who needed to demonstrate short-term returns to investors urged executives to reduce long-term thinking.

Pinto says those wishing to re-create entrepreneurship in the West can learn two important lessons from the East: accept conglomerates and keep an open mind to investment opportunities that produce good returns, but not necessarily extraordinary ones.

"The West believes it is poor business thinking to have conglomerates, and you should break up conglomerates," Pinto says. "But the East experience proves that our convention in the West is wrong."

A good model of a successful Eastern conglomerate is Tata Group of India, Pinto says, which leads in many industries: communications and information technology, engineering, materials, services, energy, consumer products and chemicals. It is good leadership that holds each part together for the benefit of the group.

"Secondly, we have a convention in the West that if the return on capital of a project is less than 15 percent, the project is turned down. In the East, there is no preconceived threshold. They think, 'OK, if I get a 9-10 percent return, then it is more than (the return from) savings in a bank'."

As a consequence, Eastern businesses are busily investing in capital projects, while Western businesses keep on accumulating cash, which is then used to pay special dividends to shareholders or buy back shares, he says.

Other suggestions Pinto has for Western companies include expanding the assessment period for executives before giving them financial rewards, and for government to reduce capital gains tax for money made by shareholders over the long term, to encourage long-term thinking by executives and shareholders.

To drive these changes, in 2010 Pinto founded the think tank New City Initiative, which brings together many asset managers who believe in the power of long-term business decisions and wish to promote this business model.

Pinto says this change of mindset by Western companies will not be easy, but he feels encouraged that Western governments and businesses have been going through a "soul- searching" process since the global financial crisis.

"At the end of the day, the real issue is, are we (the West) doomed to have GDP growth of 1 percent a year, or shall we return to a model that we can generate 3-5 percent. The response is not a welfare estate, but entrepreneurial capitalism."

cecily.liu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 03/28/2014 page32)

Today's Top News

Partnership with Belgium, EU highlighted

Turkish PM wins local elections

Monday's search for MH 370 resumes: AMSA

Families of flight MH370 passengers 'need closure'

Greece passes new reform bill

Dobass demonstrators demand referendum

MH370 relatives demand answers

Turkey starts local elections

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|