Mission possible: to untie tongues

Updated: 2014-03-21 08:19

By Mike Peters (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

|

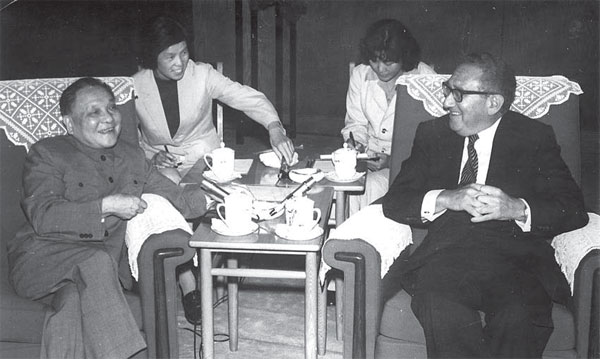

Shi Yanhua (left) interprets for Deng Xiaoping and former US secretary of State Henry Kissinger in 1982. Provided to China Daily |

They are the people who always hover, almost imperceptibly, in the background, but from there they have a front row as spectators of history

Today, a well-educated young person in Beijing will have plenty of chances to meet people from outside the country.

The first American Shi Yanhua ever spoke to, in the 1970s, was Walter Cronkite, the famous TV news presenter.

"When I entered the foreign ministry," says the retired translator for former leader Deng Xiaoping and other Chinese leaders, "there were only 49 countries that had diplomatic relations with China. During the 'cultural revolution' (1966-76) there was chaos, very few diplomatic functions and so on. You didn't have much work. You didn't learn much."

But China's seat in the United Nations was restored in 1971.

"It happened that my husband and I were sent with the first group to New York. He was a French interpreter; I was an English interpreter," she says.

"At that time there was no direct flight between China and the United States. We had only two foreign airlines, Pakistan's and Air France, so we took Air France from Shanghai to Burma to Karachi - I think then to Teheran and then Cairo - and then finally to Paris. We went around the biggest circle on the Earth."

Back then, she says, Western airlines could not fly over Soviet territory.

When they boarded the flight to New York, there were Americans on board, including two cameramen and a tall man who went up to the first-class seats to sit near the chairman of the Chinese delegation, Qiao Guanhua, vice-foreign minister.

"It was Walter Cronkite, from CBS," Shi says.

"The American journalists had checked to find out what flight the Chinese delegation would take, and they booked the same ticket. That impressed me very much."

After Shi left high school in Shanghai, she was recruited when the foreign ministry went looking for bright young people to study at what was then its Foreign Languages Institute.

The political environment was very different then. In high school she had studied Russian.

"China was secluded and didn't have many relations with Western countries," she says.

"But I thought English was the language of the future. So at university we just learned English from our lecturers, who were very good, but they had learned from books, and we didn't have much chance to listen to native speakers or to read newspapers. We read classic English literature. I liked Charles Dickens best. But I also read Jane Austen and other writers."

While she was taking post-graduate courses in English in 1964, China and France established diplomatic relations.

"France was the first major Western country to do that, and the late premier Zhou Enlai thought there would be an opening-up of our diplomacy. We would need more interpreters."

She soon found herself in the foreign ministry's translation department.

"What I had learned (before) was just language, but there you had to learn foreign affairs, foreign relations. For instance, when I was asked to translate a diplomatic note, I didn't know the formula and the style."

She also had to learn to type.

"You couldn't afford to make mistakes. In the translation department, if there were three mistyped letters, you had to retype the whole letter."

After the numbing period of the "cultural revolution" came the surprise opportunity to go to New York.

"As the plane was approaching New York, I saw all of the parked cars at JFK airport -they looked like toys in the sunshine. I was amazed. So many cars. In Beijing at that time, we didn't have any private cars."

When they arrived, about 200 journalists were waiting for them on the runway ramps. But United Nations officials quickly ushered the delegation past them and into the terminal building.

For the first few weeks, Shi felt like she was in a zoo.

"We were followed by everyone. Every day on the TV screen you could see the Chinese delegation."

Reporters asked the same questions: Where have you been? What did you eat? Did you like American food?

"Actually, we didn't," says Shi, chuckling.

"We had never had any Western food, so it was strange for us. In the Chinese diet, at lunch or dinner we would have a soup. But there was no soup. Then we asked for soup, and they made a very good consomme of chicken soup. Otherwise, for vegetables, they just boiled them. Many of my colleagues were not used to it. Fortunately, they had brought some cans of Chinese pickles and sour cucumbers and chilies. That is how they survived."

She was quickly learning how to deal with cultural challenges as she coped with language.

"One day there was a middle-aged lady who ran after me and asked, 'Are you from Red China?'" she says.

"I wasn't very happy, because I thought in her vocabulary "red" did not mean a very good thing - it means revolutionary and violence and so on. But I saw her expression - it was very friendly - and so I said, 'Yes, but my country is called the People's Republic of China, not Red China'. And she said, "Oh it doesn't matter. Anyway, you are from China. That's good. It's overdue. Welcome to New York."

Many Americans who lived through World War II welcomed her and her colleagues, recalling the days China and the US fought side-by-side.

"So this brought our two peoples closer," she says.

"One American man told me: 'You know, in my younger days in primary school, my teacher told me that if you want to go to China, dig a hole and, underneath, it's Shanghai.' Later president Reagan, when I accompanied him, told me the same story, and I told him: 'What a coincidence: We were told in primary school that if we dig a hole, we would reach New York'."

Being an interpreter in New York was not easy at first.

"I wasn't used to the American accent. We had been taught the Queen's English."

Translating over the phone, she says, required particular care.

"But I considered this my chance to study the language, because I never had the chance to study abroad. It was equivalent to going to university again. I could watch television. I took part in diplomatic talks and so on."

Among those she interpreted for was Henry Kissinger, the former US national security adviser and later secretary of state.

Interpreting for Kissinger was difficult, she says, because of his strong, throaty voice and German accent.

"In addition, he was a professor of philosophy. He was used to using big terms - and Latin words - and once he said something about 'hiatus'. I will never forget this. Many new words I could guess from the context, but when he said there was a hiatus in relations between the then Soviet Union and the United States, I was thinking 'What is hiatus?' I didn't know.

"So I had to ask: 'What is hiatus?'"

He looked at me and said: "Pause."

In 1975 she was called back to Beijing to act as interpreter for Chinese leaders, mainly for talks between them and Americans.

In 1977, when Deng Xiaoping assumed official duties for the third time, she says, she gradually became his interpreter.

"He was a man who looked very serious. He was hard of hearing, so he didn't say much, but sometimes he would be very humorous.

"For instance, in Singapore, once we had a meal together - not a banquet - before we left. He asked for some chilies, very small chilies, very hot, and then he said he would like to give me some. I said no, I couldn't eat chilies; they are too hot, not good for my throat or my voice.

"Then he teased me. He said: 'You must eat some chilies, some hot things - otherwise you are not a revolutionary.'"

michaelpeters@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 03/21/2014 page25)

Today's Top News

China, the Netherlands seek closer co-op

Crimea is part of Russia

Images may help solve jet mystery

Obamas wowed by China

Xi leaves Beijing for first trip to Europe

Beijing beefs up hunt for missing jet

Putin signs law on Crimea accession

Australia to resume ocean search for missing jet

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|