Rate ceiling has no reason to stay

Updated: 2013-10-04 08:58

By Zhou Feng (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Liquidity and debt crisis hitting eastern China highlights need for reform

Last week I had dinner with a long-time friend, a senior manager at the Wuxi branch of a national bank.

She had a lot to complain about. "Life's tough," she said, referring to what she called the worst time since she joined the bank more than 13 years ago.

Bad debts were snowballing because of a combination of factors such as solar giant Suntech Power's bankruptcy, steel trading firms' liquidity crisis and the massive breakdown of reciprocal loan guarantees among small and medium-sized enterprises in eastern China.

Wuxi, an industrial city and solar technology hub in Jiangsu province close to Shanghai, turned out to be the eye of this "perfect financial storm", and there is no way that her bank can achieve any of its yearly goals, she said.

"By the end of the third quarter, my department's revenue was less than half the yearly target," she said. She heads the bank's foreign exchange department.

"I have heard we will not get our third-quarter bonus due to poor performance."

I offered my sympathy, and said the worst is probably over, but in my heart I knew that the same crisis will be repeated if these state banks' financing costs remain artificially low.

On the surface, the financial storm hitting lenders hard in the eastern provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangsu is a result of many problems unexpectedly converging. But at its root, the crisis is a punishment for those banks which have indulged in an unreasonable lending spree by taking advantage of their cheap and large capital base.

To solve the problem, the deposit rate must be liberalized so that banks will learn to lend with caution, and improve relations with customers and quality of service.

In China, the deposit rate is set by the People's Bank of China, the central bank, with commercial banks given leeway to float the rate at a premium of 10 percent maximum. This remains the last barrier to China's full liberalization of interest rates.

The benchmark one-year deposit rate now stands at 3 percent, meaning that banks can attract depositors with the highest rate of 3.3 percent.

This rate is apparently below market cost, given that the consumer inflation rate stands at about 3 percent, and one-year government bonds yield 4 percent. If you consider the rate fund managers in Zhejiang and Jiangsu pay to get financed, which now stands at more than 11 percent on a yearly basis, the 3.3 percent deposit rate ceiling can never be regarded as high cost.

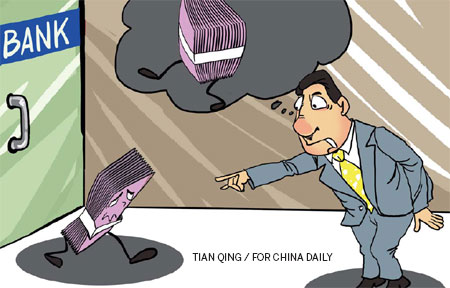

Since banks can easily get cheap capital, they do not carefully manage the money. After all, it is human nature that people will not cherish things that they are given easily.

With that mentality, Chinese banks traditionally are not good at loan management. They have a habit of reducing the non-performing loan ratio simply by boosting the base of total loans instead of improving loan quality.

The situation was made worse by the 4-trillion-yuan ($653 billion) stimulus package released by the government to solve the 2008-09 financial crisis.

Banks were given a large amount of money, and they were asked to lend it out to propel economic growth. To achieve the lending goal, banks frantically handed out loans to shadow bankers and small companies, other than to their traditional customers - big companies.

But the truth is, the banks significantly but unduly loosened qualification and asset scrutiny. They used to take tangible properties as a guarantee, but during those years, futures contracts, third-party collateral and reciprocal loan guarantees were excessively used.

So when the stimulus came to an end, with liquidity tightened and economic growth slowing, high leverage rates bit into companies, resulting in an increasing number of defaults and bankruptcies.

Banks then became worried and started to call in outstanding loans from small companies, even though the loans were not mature. That aggravated the financial difficulties of these companies and caused more defaults and bankruptcies. A vicious circle took shape and evolved into the current crisis in coastal China.

The mess may not have happened if the deposit rate had been fully liberalized.

Clearly, if deregulation takes place, the deposit rate will go up, with smaller banks, pressured by having a slim capital base, taking the lead.

That will ultimately add to the financing cost for all banks. With rising costs, banks will have to focus more on risk management, qualification checks and service improvement to make sure interest income is stable and safe. If that happens, the lending spree may be averted.

This is just like the case of Chinese manufacturers, which used to bask in cheap costs thanks largely to the demographic dividend. As money could easily be made with cost advantage, they did not bother to build brands, improve services or strengthen internal controls. But when costs go up, as we see now, they have to upgrade and be cautious in making decisions.

Similarly, scrapping the deposit rate ceiling can help improve the overall quality of Chinese banks.

Full liberalization of rates can lead to more competition and narrow profit margins for banks, but they will be pushed to adjust to new challenges by changing their business model and become more efficient.

China should accelerate liberalization of deposit rates also because the artificially low rate is choking the country's already tough endeavor to become a consumption-driven economy.

Chinese people are the world's most enthusiastic savers. By August, savings of the Chinese exceeded 43 trillion yuan, a historic high and the world's largest. That figure translated into 30,000 yuan per capita and meant that the public's saving ratio vaulted over the 50 percent mark, beating by far that of any other country, according to the People's Bank of China. The world average saving rate is 20 percent.

The Chinese have a habit of saving every penny they can for a rainy day, and they tend to spend big only after they feel they have saved enough for uncertainties.

But the ceiling on deposit rates, coupled with high inflation, force many of them to save more before they dare dig deeper into their pockets.

China experienced negative real interest rates for most of the past 20 years. In such a situation, the deposit return on one's savings is lower than the inflation rate, which means the value of savings depreciates. As Chinese people tend to spend big only after they save a target amount as a life reserve, the deprecation will only make them feel the need to save more.

According to a study by the Research Center for International Finance at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the real interest rate and saving rate are negatively correlated in China. The negative correlation stays even after researchers singled out all other factors that can potentially affect people's saving habits.

In this sense, the government's reluctance to allow banks to set deposit rates distorts the value of people's savings, reduces family wealth in real terms and prevents the Chinese economy from transforming into a consumption-led one.

The deposit rate ceiling must be scrapped, but the liberalization must come with a measured approach.

Banks, companies and consumer need time to adjust to changes. Financial infrastructure, supervision and regulation all need time to be put in place to ensure a smooth transition.

A deposit insurance system ought to be established first before significant deposit rate reforms are made.

The liberalization should start with long-term and large deposits, and banks should be allowed first to issue negotiable certificates of deposit.

But for the good of the banks and China's sustainable growth, it would be best if full liberalization can be achieved within three years.

The author is a Shanghai-based financial analyst. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily European Weekly 10/04/2013 page11)

Today's Top News

China, Russia co-work for security in Asia-Pacific: Xi

Animal welfare to be added in training

Talks 'can help Chinese banks' in UK

Robust home sales during holiday

APEC 'should take lead' in FTA talks

Beijing targets polluting cars

China warns US, Japan, Australia over sea issues

US on path to default if Obama won't negotiate

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|