The might of copyright

Updated: 2013-10-04 08:57

By Todd Balazovic and Chen Yingqun (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Respect for intellectual property rights in China has led to deals that publishers everywhere are benefiting from

As book publishers grapple with ways to adapt from print to new media, buying and selling copyright has become the lifeblood of an industry in transition. When the audio file-sharing program Napster was introduced in the late 1990s, it shook the copyright world and sent record executives scrambling.

A decade after a legal tussle that eventually forced Napster into bankruptcy, book publishers are facing challenges similar to those of the music industry then - working in an industry where output is increasingly in digital format, and where abundant, cheap content is exchanged online.

"We really are facing the same challenges of the music industry 10 years ago," says Scott Beatty, chief content officer for Trajectory Inc, a US digital distribution company that works closely with Chinese authors.

"The key for the big publishers is to figure out how to move beyond bricks and mortar retail shops and figure out new distribution channels and new distribution methods."

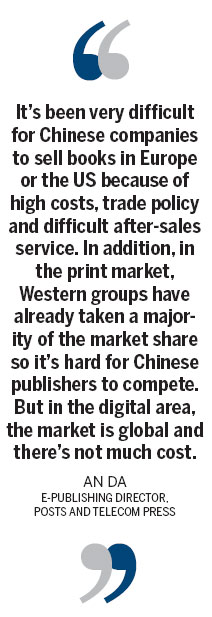

China, the most populous country, provides the perfect opportunity, he says.

"Think about it: there are more children in China than citizens in the US and a lot of them are looking for English books.

"China is the single most important publishing market on the planet."

Working with Chinese publishers to buy and sell copyright, publishing houses such as Penguin and McGraw-Hill are taking advantage of the country's insatiable thirst for literature, in whatever form it comes.

"Copyright trading is and will be the main trading form of the publishing industry, covering the biggest scale and making the most profit," says Tan Yue, president of China Publishing Group Corp, the country's largest publishing house.

The record for copyright agreements reached between Chinese and foreign publishers in a year has already been broken this year. At the 20th Beijing International Book Fair late in August, more than 3,600 copyright deals were signed, a double-digit growth from the previous year.

|

In transactions dominated by business, education and children's books, 650 publishers from more than 76 countries bought and sold copyrights from and to Chinese publishing houses.

Lax policing of intellectual property laws was once a huge cause of concern for foreign publishers, but as the number of copyright sales has risen, so too has confidence in China's book market.

Five years ago street vendors peddling low-quality prints of foreign and domestic books put a spoke in the efforts by overseas publishers to make inroads into China with English-language books.

Malleza Fan, senior publishing manager of higher education for McGraw-Hill, recalls walking outside the company's office in Beijing to see a vendor selling pirated copies of its books at one-tenth the normal price.

There was a marked difference between the genuine product and what was being sold on the street, which was often downloaded from the Internet and mass printed at rock bottom prices, she says.

"The quality was so low. People would pick a book out of the stand and the cover would fall off."

But as Chinese publishers trying to market their wares overseas have worked more closely with companies in the West, there has been recognition that the regulators need to do something, and action has ensued.

In June the National Copyright Association launched a campaign called Sword Net aimed at finding and shutting down those uploading literary works illegitimately online.

The authorities are promising more investigations and harsher penalties for illegal books, music, games and software found on the Internet, and more than 2,000 people were arrested for copyright infringement in the first half of the year.

A previous campaign against copyright and trademark pirates began in October 2010 and lasted eight months, and more than 3,000 people were arrested.

"We're still cautious about it, but it has got better," says Annie Oswald, director of media publishing and rights manager for Franklin Covey, a US business publisher that focuses on self-improvement titles.

Oswald, visiting Beijing to meet the company's Chinese publishing partners, says that by signing copyright agreements with local publishers the company has been able to securely expand its reach into China.

But even with less competition from knock-off books, prices for books in China, print or digital, are often half the price overseas, she says.

"The model here is that you can have cheaper products because you have larger volumes," she says, adding that domestic publishers set the price for content to match local markets.

Frog, by the Nobel Prize winner Mo Yan, which was at the top of China's best-seller list at the end of last year, is being sold for 35 yuan ($5.7; 4.2 euros), compared with the average price of a hardback from the New York Times best-seller list retailing at 183 yuan.

Franklin Covey's international reach is reflected in the number of languages in which its books are published, 30; and 20 percent of its international copyright agreements have been signed with partners in China, Oswald says.

For foreign publishers, navigating China's complex copyright laws can be daunting. One publisher has responded to the need to better understand the laws by working with the central government to translate and disseminate information on intellectual property rights.

Dutch information giant Wolters Kluwer signed an agreement with China Commercial Press at the beginning of last month to translate a series of reference books on patent cases in China.

The series, titled Selective Reading of Chinese Patent Cases, will include English translations of some of China's most complex and earliest intellectual property cases, many involving foreign companies.

Kevin Entricken, chief financial officer of Wolters Kluwer, who signed the agreement with Yu Dianli, general manager of China Commercial Press, says: "You have a lot of interest in the growth in China. You have a lot of companies entering into this market that want to understand what the IP law is and want to understand what the patent law is.

"The fact that businesses in China want to tell the world, 'This is what we're doing; this is how our copyright is evolving,' is a very positive sign."

The companies are also working on translating a series of international law books into Mandarin aimed at guiding Chinese businesses looking at going global.

The Wolters Kluwer Legal Translation Series has received the imprimatur of the central government and is part of China's 12th National Five-Year Important Books Plan. This aims to bring high-quality translations of business, law and health materials in and out of China.

Related Stories

Injections of ink for improved well-being 2013-10-04 08:57

Tongue-tied no more 2013-10-04 08:57

Digital revolution has a long way to go 2013-10-04 08:57

Price control a must for Chinese publishing 2013-10-04 08:57

Today's Top News

China, Russia co-work for security in Asia-Pacific: Xi

Animal welfare to be added in training

Talks 'can help Chinese banks' in UK

Robust home sales during holiday

APEC 'should take lead' in FTA talks

Beijing targets polluting cars

China warns US, Japan, Australia over sea issues

US on path to default if Obama won't negotiate

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|