Chinese system in its own context

Updated: 2013-08-16 09:07

By Andrew Moody (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

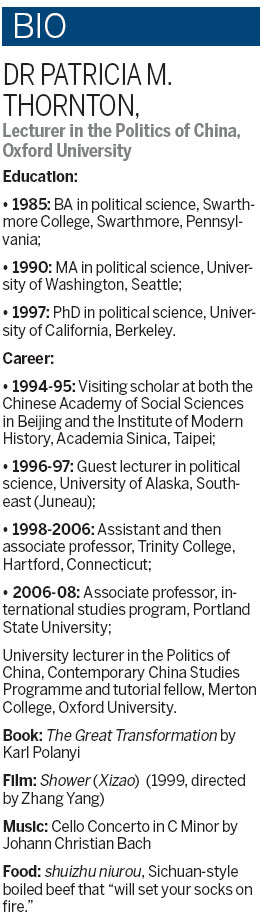

Patricia Thornton says Western political science generally uses research models that often do not work well in the Chinese context. Nick J. B. Moore / For China Daily |

Country is no more or less stable than any other system, says academic

Patricia Thornton believes many make the mistake of viewing China through a Western prism.

The lecturer in Chinese politics at Oxford University says it is important, instead, to see the world's second-largest economy on its own terms.

"Western political science generally uses research models that derive from Western experience and they often don't really map well in the Chinese context."

The American academic says it is often assumed China will evolve from its Communist state-planned system to a Western liberal democracy as though this was a naturally ordained trajectory.

"For someone who studies Chinese politics you often feel you are trying to explain away that gap and you can then find yourself tangled up in some esoteric debates trying to explain why China's different," she says.

Thornton, a sunny personality with an impressive academic reputation, says that China's differences are at least recognized at Oxford, where she has been for the past five years.

"What I found really refreshing about coming here to Oxford is the way the discipline of politics is constructed in the UK - and in Europe too - is different from the way it is constructed in the US.

"Studying China here is connected to Oriential studies, focusing around a very intensive study of language, culture and philosophy as against the US, where it comes out of a social science tradition."

Thornton was speaking in her study accessed by a narrow spiral wooden staircase in one of Merton College's ancient buildings.

A popular figure at the college and known as Tia by everyone, Thornton says she is constructing a program at Oxford that assesses the Chinese system in its own context.

"What I am trying to do is build a program for students to study Chinese politics. Most political science starts with basically a deductive model, which is drawn largely from Western experience, and when you plump it down really inelegantly in the Chinese case, China does not seem to measure up. It becomes either an imperfect or an outlying case."

Building such a program means staying away from presumptions that the Chinese government just resembles other Communist systems, she says.

"It is about discovering what Chinese intellectuals, Chinese scholars and, indeed, Chinese people say about themselves. This way you can begin to build up a more generalized understanding of certain mechanisms, goals and processes that exist within China. Ultimately the goal is then to reverse the position and say why the West differs from the Chinese example," she says.

Thornton, who is originally from New York, says her fascination with China dates back to her childhood in the US.

"We moved to New Jersey when I was 4 and I liked to read a lot about China. It seemed interesting and exotic to me at the time. I read anything I could get my hands on.

"By the time I reached my early teenage years it was the 'cultural revolution' (1966-76) and there were some interesting reports coming out of China but little was actually known then."

She avidly read the dispatches of the legendary New York Times correspondent Fox Butterfield, who was then posted in Beijing.

"He wrote a series of articles, some of them that appeared on the front cover of the (New York) Sunday Times magazine. I just found what the images of what life was like in Beijing in the 1970s and early 1980s absolutely captivating."

She studied the Chinese language majoring in Sino Soviet studies for her undergraduate degree at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania; and went on to do a master's at the University of Washington and then a PhD at Berkeley - at both universities studying under Elizabeth Perry, the Sinologist who now holds the Henry Rosovsky chair in Chinese politics at Harvard.

Thornton made her first trip to China in 1985 when her uncle, who worked on the New York subway system, gave her $500 when she graduated.

"I came from a working-class background so that was an unimaginable sum of money for me," she says.

After paying for her round-trip ticket to Beijing she had $100 when she arrived and it was more than enough to travel extensively for four months, taking in Xi'an, Hunan and the Three Gorges.

Thornton embarked on an academic career and had spells at both the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing and at Academia Sinica, Taipei. She progressed to become associate professor at Portland State University, Oregon, before moving to Oxford in 2008.

With her academic work she has examined more recently the legacy of the "cultural revolution" in China today but her main focus has been state-society relations since the birth of New China in 1949.

Thornton says people often make the presumption about China that what exists now is not the finished article and major adjustments have to be made.

"I wouldn't necessarily presume that any country has to do anything. I would say that China is no more or less stable than any other system and that all systems we are looking at are very much in a state of flux," she says.

"China is rapidly developing, moving so quickly along so many different registers, it is very often hard to keep up with what happened last month, last year, you know."

She says that even in Britain, the recent death of former prime minister Margaret Thatcher highlighted cracks in the edifice of what is seen as a long established political system.

"The recent death of Margaret Thatcher was really very interesting to me as an American because I began to see that her legacy had created certain deep fissures here in British politics.

"You do have exceptional transition periods, exceptional leaders who once they rise at a certain historical moment can shift the course of history, like Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping in China."

Thornton says there is a tendency among some China watchers to interpret what is going on in the country by just monitoring Chinese microbloggers.

"You certainly wouldn't want to look at Twitter or weibo exclusively as a measure of public opinion in any context because you often have the same people going to it," she says.

"I can't always get my mind around social media. When my students wake up in the morning they go to their Facebook page. It is the very fiber of their existence. I just want a cup of coffee."

She says one of the remarkable aspects of the Communist Party of China is how it has been able to adapt and survive while other systems have not, in particular, the former Soviet Union.

"The Chinese Communist Party is a Leninist political party and remains to this day in some ways devoted to the practices that Lenin described as democratic centralism and mass mobilization.

"However, rather than assume the Party is a fixed or stable model I am more interested in how it has been able to adapt and innovate. Since I began my research on Chinese politics, I have found that fascinating."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 08/16/2013 page38)

Today's Top News

List of approved GM food clarified

ID checks for express deliveries in Guangdong

Govt to expand elderly care

University asks freshmen to sign suicide disclaimer

Tibet gears up for new climbing season

Media asked to promote Sino-Indian ties

Shots fired at Washington Navy Yard

Minimum growth rate set at 7%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|