Mixing it up in the ring

Updated: 2013-08-16 09:05

By Tasharni Jamieson (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

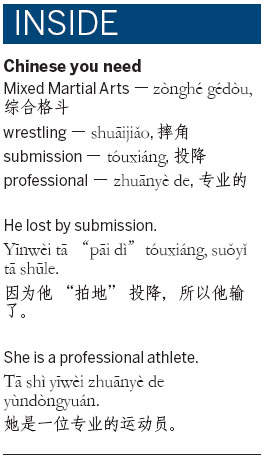

Zhang Tiequan takes down Jon Tuck at a UFC event in Macao. Provided to China Daily |

The mixed martial arts scene is at pains to get a grip on china

Even though the air is thick with sweat and grunts, it doesn't look like what you might imagine. The floor is a checkerboard of padded puzzle pieces, the type you might see at a kindergarten, and bottled water sits atop neatly stacked shoes. The flag of Brazil, harkening back to the perceived beginnings of this sport, partners the Chinese flag on the wall.

After the obligatory stretching, partners pair off; then, they square off. Sparring is rigorous, technical and painful, often involving broken fingers, torn muscles, and not a few black eyes.

The painful training is necessary. Bouts are imminent.

Zhang Tiequan stands with his arms crossed, watching his students with great regard. Directing and advising other coaches, Zhang slips a smile to two young jujitsu fighters as they grapple fiercely on the floor.

Despite being in guillotine chokes and ankle locks, they return the smile. Training is tough at China Top Team, but they all feel somewhat at home on the sweat-soaked floor.

As the best known Chinese MMA (mixed martial arts, 综合格斗 zònghé gédòu) fighter on the international scene, Zhang, "The Mongolian Wolf", hails from the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, and was the first of two Chinese fighters to be contracted to the world-renowned UFC league.

One of the founders of China Top Team, a collection of some of the finest MMA fighters in China, he currently trains and coaches the next generation of brawlers in Beijing.

Zhang started his fighting career, practicing boke (搏克), a style of wrestling specific to Mongolia and the Inner Mongolian region. At the age of 15, Zhang began to study Greco-Roman wrestling, and, in 1999, began practicing the Chinese military-inspired fighting style of sanda (散打).

"The first time I saw a video of MMA, I felt incredible," Zhang recalls, remembering when, in 2005, he was recommended for an MMA project by Chinese-American jujitsu instructor Andy Pi.

Zhang was drawn by the prospect of being able to use the many skills he had learned in his varied background.

"The most important reason was that, as a sportsman, I liked the sport of MMA itself, and I like to challenge myself." (首要原因是,作为一名运动员,我喜欢综合格斗这项运动,而且乐于挑战自我。Shǒuyào yuányīn shì, zuòwéi yīmíng yùndòngyuán, wǒ xǐhuān zònghé gédòu zhèxiàng yùndòng, érqiě lèyú tiǎozhàn zìwǒ。)

Yao Honggang, a recent bantamweight champion at Legend Fighting Championship, started his career in Chinese-style wrestling traditional shuaijiao (摔跤). But Yao soon saw profit in MMA, as opposed to wrestling.

"MMA competition is a particularly good platform on the international scene; it is widely recognized around the world," Honggang says. He and his younger brother Yao Zhiku were born and raised in Zhoukou, Henan province, the sons of a PE teacher.

Big Yao had always taken an interest in Chinese martial arts, but started to formally train in wrestling while working as a security guard for a Beijing restaurant.

"In the first two years, I practiced MMA during the day, and at night would to go to the restaurant to be a security guard," Big Yao says. "I didn't need to pay for my training because my wrestling was pretty good. The club I joined thought I might have a promising future, so they helped me out and let me train for free."

Unlike many of his friends and fellow MMA fighters, Big Yao managed to work his way up to MMA professionalism.

Big Yao, nicknamed "The Master", commented that, while the skill and physical condition of some of his colleges may be at a higher level, most people do not have the ability to fight through the rough times and low pay connected to amateur and semi-professional MMA competition in China.

"In the beginning, there is too much hard work and practice, with only a little income. Most people find an easier way to make a living, so they change to another job," he says.

Success stories such as Zhang's and Big Yao's are hard to come by, with Chinese fighters seldom making it to national, let alone international, standard. The booming sport has struggled to find its feet in the Middle Kingdom, and young professional and amateur fighters alike have faced many obstacles on the road to the bright lights of MMA stardom.

Beijing-based MMA trainer, and international business manager, Laurent Pinson, from France, has been involved in the Beijing MMA scene since its infancy, first coming to the capital in 2005.

"China often attempts to imitate the outside of things," Pinson says. "At the time it was the fighting style in vogue, Chinese fighters tried to replicate it."

It becomes a dajia (打架), or a brawl, rather than a civilized competition.

However, a break from the traditional aspects of kung fu may be the kick this sport needs for the new generation.

Cui Yihui, a 22-year-old student on his summer holiday back in Beijing from studying economics in Chicago, is one of China Top Team's eager youths who see the real-world value of a sport such as MMA, as opposed to traditional Chinese martial arts.

"Personally speaking, kung fu is just like a show; you need to make it look good," Cui says.

Zhang says that, while MMA doesn't necessarily look good, it is much more intensive and practical. "Take a look at my appearance!" He beams, sweat dripping off his brow after an intense training session in Brazilian jujitsu. "As you can see, MMA is much more real." The short, action-packed rounds in MMA may also appeal to a new generation of young people who are accustomed to instant gratification and jam-packed entertainment.

While agreeing that support for MMA will have to start from the youth in China, trainer and gym manager Simon Shieh sees that encouragement for young people in amateur competition is where the sport will get its foundation.

However, Pinson remarks that the concept of amateurism in China's MMA sphere doesn't really exist; it's all about the professional: "There are two divided systems."

Within the semi-professional system the quality of competition is fairly low and the standards in the professional system are substantially higher.

Champions rarely come through the amateur system in China, as there is little financial or moral support for those who seek to make it big.

Most up-and-coming MMA fighters, like Big Yao, are required to self-fund their studies, and simultaneously work and train, just to make ends meet. With this setback, Pinson laments that, by the time a fighter has found a way to support their dedication to MMA, it is often too late.

Despite the obstacles, Cui says on the improvement of youth support for MMA in recent years: "It's getting better and better. Now you can see many teenagers studying MMA. They use it to relax or get healthy, and it pays off."

At 24, Liu Jiajia, or Alison, is one of the few females following the MMA path. She embodies Zhang's faith, seeing him as a mentor.

"We have great respect for Zhang Tiequan," Alison says. "He has been leading us."

Regardless of how long it takes for mainstream support of MMA to kick off in China, the encouragement of the existing MMA community will ensure that those who have the passion will find their way to the guts and glory of MMA fame, whether it's in the domestic or international arena.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 08/16/2013 page27)

Today's Top News

List of approved GM food clarified

ID checks for express deliveries in Guangdong

Govt to expand elderly care

University asks freshmen to sign suicide disclaimer

Tibet gears up for new climbing season

Media asked to promote Sino-Indian ties

Shots fired at Washington Navy Yard

Minimum growth rate set at 7%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|