A humble how-to

Updated: 2013-08-02 08:58

By Duncan Pouparo (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

The art of modern day modesty 中国式谦虚

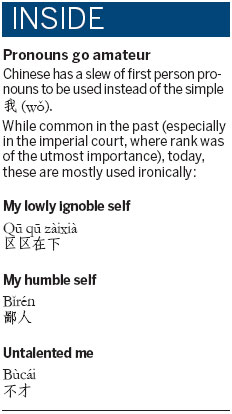

Chinese modesty, in all its self-effacing glory, is most likely a product of the country's great philosopher/instant-noodle-supremo, Master Kong - or Confucius - as he was known to his Jesuit friends.

All Chinese schoolchildren learn how wise yet humble Confucius was, memorizing such sound bite-friendly aphorisms of his, such as "when three men walk together, my teacher must be among them" (三人行必有我师焉。 Sān rén xíng, bì yǒu wǒ shī yān), which Confucius used to show that even the most brilliant people always have something to learn from others.

"Modesty", be it genuine or false, permeates Chinese culture.

The Tao of modesty

So what is "modesty" in Chinese? Let's look at the Chinese word: 谦虚 (qiānxū).

The first character, 谦 (qiān) means humble, while the 虚 (xū) is short for 虚心 (xūxīn) - self-effacing, literally "emptiness of heart".

Unfortunately, there is a thin line between modesty - being self-effacing - and being insincere. This distinction is even closer in Chinese, as the words for modesty (谦虚) and insincerity (虚伪 xūwěi) both share the character for emptiness, 虚.

In the former, it is used to mean "without arrogance"; in the latter, it is used to mean being "false and disingenuous".

The line is so blurred that false modesty is expected (even required) on some occasions, although to overdo it can also be frowned upon. Nevertheless, when in doubt, being excruciatingly modest is almost always the best course of action.

So, it is important to note that the following guide on how to be modest in a Chinese fashion is likely error-filled and lacking substance; therefore, dear reader, please accept my most humble and kowtow-filled apologies in advance, as I meekly surrender to your undoubtedly greater wisdom.

Excuses, excuses and excuses

Before you do anything in China, whether it is cooking up some greasy dongpo pork (东坡肉) for your friends, or performing a virtuoso erhu solo on a street corner, it is a good idea to lay the modesty groundwork - lower people's expectations by professing ignorance or lack of ability in anything you are about to do.

The ironically self-perpetuating mantra of the Chinese learner of English: "My English is poor" is a classic example of this stratagem. After all, you can't be disappointed if your hopes have been crushed in advance.

We can convert this mantra into a Chinese statement that can be used whenever you have to make a speech in Chinese.

I am not very good at Chinese, and for this I apologize most humbly.

Wǒ de hànyǔ shuǐpíng bùgāo, duì cǐ wǒ shēn biǎo qiànyì.

我的汉语水平不高,对此我深表歉意。

This works in almost any situation that calls for you to speak Chinese, even if your Chinese is actually good enough to recite Tang poetry while solving riddles written in oracle bone characters.

These excuses, like most nuances of Chinese culture, extend all the way to the dinner table.

At dinner engagements, custom dictates that the host will usually provide a dizzying array of dishes for their guests. But the host may still say something like:

I'm not much of a cook; bear with me if it doesn't taste good.

Wǒ de chúyì bù hǎo, dàjiā jiāngjiù chī ba.

我的厨艺不好,大家将就吃吧。

I am embarrassed that there are only few home-cooked dishes, please enjoy but don't take them seriously.

Bù hǎo yìsi, zhǐyǒu jǐgè jiāchángcài, suíbiàn chī chī ba.

不好意思,只有几个家常菜,随便吃吃吧。

To which an appropriate response might be:

Not at all, there's more than enough!

Náli, zhè zhēnshì tài fēngshèng le!

哪里,这真是太丰盛了!

Compliment counter strike!

The speed at which Chinese people are likely to offer a compliment is matched only by the speed at which that compliment is then subsequently deflected. A failure to deny a compliment is, in most cases, a social faux pas, and may be viewed as arrogance of the highest order. Generally speaking, praise should be met with modesty.

The Chinese language has developed a whole bevy of speech formulas used for the express purpose of responding modestly to lavish praise.

These can be the everyday, useful phrases like the following:

Where are you speaking? (It's kind of you to say so.)

Nǎlǐ de huà.

哪里的话。

Where? Where? (Not at all!)

Nǎli nǎli.

哪里哪里。

Or they can be slightly higher register formulas, such as:

You over praise me. (You flatter me.)

Nǐng guòjiǎng le.

您过奖了。

This small matter is not worth hanging from the teeth. (It's not even worth mentioning.)

Qūqū xiǎoshì, hézú guàchǐ.

区区小事, 何足挂齿。

All these phrases can be used by themselves after a compliment, thusly:

A: You speak such amazing Chinese!

Níde hànyú shuō de zhēn hǎo!

你的汉语说得真好!

B: Not at all.

Nǎli nǎli.

哪里哪里。

Perversely, in China, the more modestly you deny a statement can be an indicator of how much truth it actually holds. This is very much the Chinese way:

To profess one's uselessness while actually having a very high opinion of oneself.

Zuǐshàng shuō zìjǐ bùxíng, xīnlǐ què juéde zìjǐ tèbié xíng.

嘴上说自己不行,心里却觉得自己特别行。

I am not worthy

Modesty is key when both giving and receiving gifts in China. When you are presenting a gift, it is always modest and slight, a 薄礼 ( bólǐ, think "myrrh"), when you are on the receiving end of a gift, it is always a gift fit for a king: a 厚礼 (hòulǐ, think "gold").

A: It's a small gift to represent my good will. Though it can't fully represent my respect to you, but please accept it anyway.

Zhè shì wóde yīdiǎn xīnyì, bùchéng jìngyì, hái qǐng shōuxià.

这是我的一点心意,不成敬意,还请收下。

B: What a generous gift; I'm afraid I cannot accept it.

Zhèyàng de hòulǐ, wǒ kǒngpà bùnéng jiēshòu.

这样的厚礼,我恐怕不能接受。

It is generally considered polite to reject a gift two to three times before finally accepting.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese,

www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 08/02/2013 page27)

Today's Top News

List of approved GM food clarified

ID checks for express deliveries in Guangdong

Govt to expand elderly care

University asks freshmen to sign suicide disclaimer

Tibet gears up for new climbing season

Media asked to promote Sino-Indian ties

Shots fired at Washington Navy Yard

Minimum growth rate set at 7%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|