Likonomics is about reform and growth

Updated: 2013-08-02 08:55

By Song Yu (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Economy may show modest, sequential recovery in second half

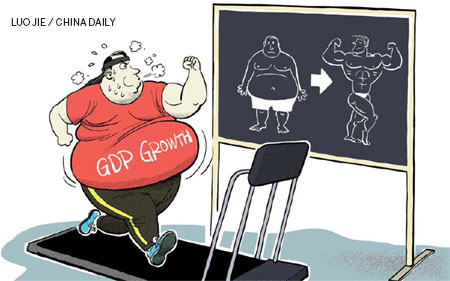

Many Chinese observers have been talking about Likonomics which aims to characterize the way Premier Li Keqiang is expected to manage the economy. There are three pillars of Likonomics often quoted: no stimulus, structural reform (short-term pain, long-term gain), and deleveraging. We believe these characterizations are misleading. The priority is not reform "instead" of growth, but reform "and" growth, as we believe it should be. Stimulus is already being implemented, though the size is likely to be small. And the concern for growth implies that the objective is not direct "deleveraging" but a controlled pace of ongoing "leveraging".

These factors imply some growth supporting policy stimulus and some structural reforms going forward but it is unlikely that either will be extremely aggressive. This more balanced approach promises to generate a growth path which is modestly lower than in past years but potentially more sustainable.

While it is true that the premier and the new administration have put a lot of emphasis on reform, slowing economic growth is clearly a growing concern. Data has mostly surprised on the downside and there is a growing amount of anecdotal evidence of stress in the economy, forcing the risk of further growth deceleration into the spotlight.

The first clear sign of this came from the policy announcement on June 26 on the redevelopment of less developed urban areas. While the policy announcement could be viewed as a social welfare measure instead of a stimulus measure, we believe it was clearly motivated by the government's growth concerns. Specifically, the announcement stated that "many areas including the urban redevelopment plan can become new growth drivers".

As a result, we have viewed this as the possible start of a series of policy measures which may seem unrelated but all have the tendency to support economic growth.

The subsequent announcements focused on information consumption (especially with regard to 4G mobile technology) as well as on environmental and energy conservation polices, all on July 12.

Domestic media also reported further policy measures to include support for railway construction and urban infrastructure (indeed urban redevelopment already had an element of this as it emphasized the need to build infrastructure to serve the newly built social housing). The wording of this was very vague so it can include almost all infrastructure including the more broadly defined areas of education and healthcare.

Apart from these announcements on the demand/expenditure side, there have been a number of announcements on the financial supply side as well. The State Council's announcement on urban redevelopment very closely followed a dovish announcement by the normally hawkish People's Bank of China on the day before June 25 on liquidity conditions. Interbank liquidity had been extremely tight until then and has since been loosened dramatically (though still not fully back to the level before the initial round of tightening in mid-May).

The government has since announced its intention to better utilize existing monetary and fiscal stock, as opposed to being dependent on new flows. Early last week, the Ministry of Finance directed various government agencies to speed up the pace of fiscal expenditure.

The PBOC also followed up with some changes to the interest rate setting mechanism, especially the abolishment of the floor on bank lending interest rates.

While the likely effectiveness of these measures is less clear at the moment, and some, especially the abolishment of the floor for lending rates, are likely to have minimal near-term effects, the intention of providing more financial support for the real economy is clear.

As a result, these measures do not suggest wholesale "deleveraging" but rather a controlled pace of continued "leveraging". Although in the second quarter of 2013, nominal GDP growth was only 8 percent, all measures of aggregate liquidity growth still well exceed this level (loan and M2 growth both just slightly above 14 percent year on year in June). Even though June liquidity conditions were extremely tight, total social financing growth was still 20.2 percent year on year. With further measures to support growth including fiscal measures, we believe the overall level of leveraging as measured by the liquidity supply/nominal GDP ratio will still go up - though at a slower pace than in recent years.

We believe this combination of maintaining macro stability while furthering structural reform is sensible. The two goals are not mutually exclusive though they will sometimes be at odds (as in the case of environmental protection which often puts pressure on activity growth). Indeed, without further reforms to the fundamental economic structure, slower growth amid very tight liquidity conditions as in June could worsen the economic structure because private sector businesses, many of which are innovative SMEs, tend to suffer more in this environment.

Furthermore, although there are many who believe that growth is currently less of a concern as employment conditions appear to be relatively stable, the NPL ratio remains low, and CPI inflation is largely steady in the 2 to 3 percent range, these are at least partially the result of considerable efforts by government institutions.

In a fully liberalized financial system and labor market, employment conditions and NPLs would likely be somewhat worse by now. As this level of support given by the government cannot be sustained indefinitely, we believe the premier is quite right in emphasizing growth stability during the reform process.

To say the new administration pays significant attention to growth does not mean that its focus on growth is unchanged. Indeed, the tolerance for slower growth is likely to be greater than in the past decade and there is a greater emphasis on other goals such as reform, environmental and risk management issues.

But the administration is clearly not likely to tolerate slow growth as much as in the late 1990s when the Chinese economy experienced deflation for as long as five years while undergoing monumental structural reforms, including restructuring of the government, SOEs and the entry into the WTO.

So while growth concerns related to Likonomics have some truth to them, we consider them to be overblown. Rather, we expect the new administration to take a moderate approach to cyclical management and structural reform.

As a result, we will see some growth and some reform but neither will likely be extremely aggressive. More specifically, we believe the current cyclical management plan will be mostly dependent on fiscal instead of monetary measures to support demand growth in areas mentioned above (in terms of urban redevelopment etc). This can be done via spending some of the funds allocated (therefore counted as fiscal expenditure) but not spent by the fiscal funding receiver, especially in light of the saved funds from the anti-corruption campaign.

By the end of June, there were 3.4 trillion yuan ($554.3 billion, 417.4 billion euros) of fiscal deposits (this is what the government deposited at the central bank) and 14.7 trillion yuan of other deposits made by government agencies and other state-funded public organizations (these are deposited at commercial banks).

While certainly not all of this money can be spent, some of it can be, and this means a relatively large amount of actual spending can occur without impacting the official budget deficit number though it is not clear how much exactly can and will be spent. Additional support could come from faster fiscal expenditure within the year.

A large chunk of fiscal expenditure is scheduled to take place in the last month of the year, which will impact the economy early the following year more than in the current year. Bringing it forward can therefore give more support to the current year's growth without changing the annual budget. A third option would be more broadly defined public-sector spending including by state financed or controlled organizations and SOEs. Encouraging them to spend more will not impact the fiscal budget, yet may have some positive impact on near-term growth.

In terms of fundamental reforms, there has been much hope for the third plenary session of the 18th Party Congress. While we believe we are most likely to see more on fiscal and financial reforms, other fundamental changes such as the land system (which is very closely linked to urbanization and property sector development) and SOE reform are much less clear.

We expect the economy to show a modest sequential recovery in second half of 2013 as a result of the domestic policy initiatives and expected recovery in external demand. However, the recovery will likely be mild and year-on-year growth may still moderate slightly further because of a high base from last year, especially in the fourth quarter of last year. We believe that fundamental reforms, especially the reduction of the administrative burden pushed by Premier Li, will help China's potential growth rate over the longer term. However, the potential growth rate is still likely to be on a steady downward trajectory over the long term, given the demographic transition and diminishing productivity gap with developed economies.

The author is an economist with Goldman Sachs / Gaohua China. The views do to not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily European Weekly 08/02/2013 page10)

Today's Top News

List of approved GM food clarified

ID checks for express deliveries in Guangdong

Govt to expand elderly care

University asks freshmen to sign suicide disclaimer

Tibet gears up for new climbing season

Media asked to promote Sino-Indian ties

Shots fired at Washington Navy Yard

Minimum growth rate set at 7%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|