Turning point on labor

Updated: 2013-07-19 09:17

By Chen Yingqun, Qiu Bo and Cecily Liu (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

A student uses a lathe to produce a component for his performing engineering operations qualification at Warwickshire College in the UK. Provided to China Daily |

Active, prudent steps needed to enhance technical skills of migrant workers

The road to sustainable urbanization in China depends largely on the structural shift from manufacturing-fueled growth to the development of a knowledge economy, for which education and training plays a central role.

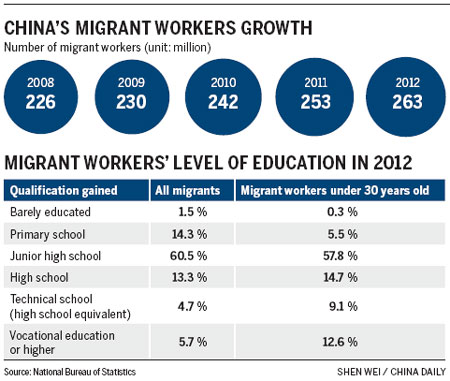

Across the country, migrant workers are flooding into city centers to provide an abundant labor pool. According to data provided by the National Bureau of Statistics, in 2012, China had about 262 million migrant workers, an increase of 37 million from 2008.

However, as China shifts gears to more high-tech and service industries, migrant workers will also need to upgrade their skills.

What makes this shift paramount is the fact that, even among young migrant Chinese workers under the age of 30, only 57.8 percent have been educated up to junior high school level (about 15 years old), according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

"Many younger migrant workers, commonly those born after 1980, aspire for an urban life, and the one barrier they experience is the gap in skills between them and the urban population," says Zhan Changzhi, a vocational education expert from Hainan University.

"Most of the job vacancies in the cities are in factories and services industries, and as such not many migrant workers are equipped with the skills to fill these roles. This is why vocational education has big potential in China," Zhan says.

According to Zhan, most urban jobs require highly skilled workers, as Chinese companies are gradually moving up the value chain. At the same time, improving living standards in cities also means urban consumers are now more demanding about the services they receive.

"In the past, migrant workers could go through a training process of 10 days to a fortnight before they were ready to start work, because they typically worked in jobs like parcel deliveries on motorbikes, which require little skill," Zhan says.

"But nowadays, there are many posts in urban factories that demand highly skilled technicians, which means students need to undergo extensive training."

Despite an availability of vacancies in cities' services and high-tech sectors, vocational education providers are still finding it hard to recruit students because vocational education is seen in China as less respectful than university education, he says.

Wang Fengqin, a 17-year-old high school student from Wangmo, a remote county in Southwest China's Guizhou province, concurs with Zhan's observations.

"My mother wanted to send me to a technical school rather than high school, while the family elders insisted that I would have a better future after high school graduation," she says. Wang's mother, who is a migrant worker in coastal Zhejiang province, believes vocational education is more suitable for her daughter.

Several other students who are likely to end up as migrant workers also share Wang's dilemma.

Zhan says that most of the young people in China aspire to be a civil servant, whose average salary is about 4,000 yuan ($652; 498 euros) a month, much below the average salary of 8,000 yuan that some highly-skilled technicians can earn.

But since civil servants receive better benefits, more students aspire for those jobs, and the only route to achieve this is university education, and not vocational education.

"This perception is a great challenge, which China needs to overcome with government policy encouragement, and some improvements have been made already," Zhan says.

He adds that it is encouraging to note that the Chinese government has invested heavily for the training of students at vocational education colleges. However, he says the government should also remove career barriers for vocational education graduates from a policy perspective.

"We could learn important lessons from Germany's vocational education system, including the investment they place in vocational training ideologies, methods and resources.

"Germany firmly believes that economic development is inseparable from vocational training, which is why the government, companies and colleges all invest in vocational education," Zhan says.

With established vocational training systems at home, many German and British education providers and government departments have been keen to share their experiences with China.

They often set up training organizations in partnership with Chinese companies or government departments. They also work closely with European manufacturing and advanced engineering companies in China, who require highly skilled technicians that are familiar with working in an international corporate culture.

One example is Tianjin Sino-German Vocational Technical College, established in 1985 as a partnership between the Chinese and German governments.

Offering courses in electro-mechanical specialties, languages, economic management and art design, the college follows Germany's dual occupational training model, which combines classroom learning with hands-on practice.

Over the years, the Sino-German College has worked with several multinational companies including Siemens and Bosch, to run training courses that focus on hands-on experiences. The students are given opportunities to work at the partner firms during their studies, and many of them end up becoming full-time employees.

"This model of dual occupational training places its central focus on companies, as the training is tailored more toward their needs," says Zhang Xinghui, president of Sino-German College.

"In Germany, companies select suitable students and fund their training. Although students do not have an obligation to work for these firms, more than 90 percent choose to do so ultimately," Zhang says.

According to Zhang, the Sino-German College is now in its third year of cooperation with Bosch, and the course has received excellent feedback from students.

He says the college is responsible for enrolling students in its courses, while Bosch selects a small number of students it wants to invest in, and these students then become part of special classes that follow a curriculum designed for Bosch's needs.

Zhang says that as China develops high-tech industries, it creates a growing demand for skilled workers that the Sino-German College is constantly changing its courses on offer to follow.

"One example of a new course we started in recent years is aircraft manufacturing, as a result of China's aerospace industry growth. We developed a syllabus based on industry needs, and we brought in European experts to help develop this course," he says.

Zhang says a key lesson China's education system could learn from Germany is allowing children to follow their interests at an early age, so technicians can become highly skilled through training over a long period of time.

"In Germany, students as young as fourth grade in primary school can choose a vocational education route if that is where their interests are," Zhang says.

"Typically the students with less talent for academic learning will choose vocational studies but eventually they can become respected technicians who demonstrate great dedication and professional ethics."

He says that in comparison Chinese students are required to take a large number of core subjects all the way to the end of high school, and hence have a late start in acquiring technical skills compared to Western workers.

Zhang's views are shared by Gao Hong, CEO of China German Education Group, who adds that vocational training has greatly helped countries like Germany develop advanced technologies because it teaches students important values like dedication and the constant willingness to learn.

"In Germany, technicians follow a culture of constant learning, so they readily return to education to update themselves on the latest skills, or acquire new knowledge when they change jobs or positions," Gao says.

Gao says another advantage of Germany's vocational education system is its responsiveness to market needs.

For example, on average about 30 professions cease to exist every year because the specific skills concerned are no longer needed in the job market. But at the same time new occupations are created, so vocational education is essential to train staff, Gao says.

There are several important lessons for China to learn, Gao says, as the nation is in the process of upgrading its industries, and efficient vocational education will help boost productivity.

"China has an abundance of labor. Even the number of new generation migrants (born after 1980) amount to over 100 million, and they provide big opportunities to propel the economy, and as such improving their skills levels is important," Gao says.

China German Education Group currently focuses on supporting and advising the Chinese government and vocational education colleges, and at the same time it also provides vocational training courses for companies, Gao says.

Good quality vocational training courses can even be a route for academic graduates to fit into China's increasingly challenging labor market, says Britta Buschfeld, head of recruitment, training and vocational training services for the Delegation of German Industry and Commerce (AHK) in China.

She says that China needs to work on improving the image of vocational education, so that parents and students will not stick to only academic careers.

To help vocational education organizations and companies implement good programs in China, AHK provides quality assurance and certification services, as well as matchmaking and consultation services.

Meanwhile, training is also taking place at many service industry companies, including the hospitality sector and senior care, as China's urbanization process has created increasing demand for these industries.

One example is Shanghai Kaijian Huazhan Senior Care Service Co, a senior care home that provides training classes for its nurses.

"We think training for nurses is extremely important to provide high quality care," says executive director Michael Li.

He says training encompasses many techniques, including how to get to know patients' habits, family backgrounds and personalities, and how to persuade patients to take medicine, to maintain a good lifestyle, or take a shower.

"Such small tasks require tremendous skills and technical knowledge, as well as a positive attitude and teamwork spirit, which is why training is important," Li says.

To bring best international practices to Shanghai Kaijiang Huazhan, Li's team visits Western countries like the US to learn from their nurses at senior homes, and then brings this knowledge back to its nurses in China.

"We hope to bring Western experiences to China, but we also want to learn lessons from the mistakes Western countries have made so we can avoid them," Li says.

Looking into the future, Zhan says China urgently needs to improve the skills of migrant workers so that they can better integrate with city life.

"China's new generation migrants will form the basis of our urban industry workforce. And education and training will play a key role in matching their skills levels with what is required in China's urban centers", Zhan says.

Contact the writers through chenyingqun@chinadailly.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 07/19/2013 page22)

Today's Top News

List of approved GM food clarified

ID checks for express deliveries in Guangdong

Govt to expand elderly care

University asks freshmen to sign suicide disclaimer

Tibet gears up for new climbing season

Media asked to promote Sino-Indian ties

Shots fired at Washington Navy Yard

Minimum growth rate set at 7%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|