Carpe diem, capture carbon

Updated: 2013-07-19 09:16

By James Smith (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

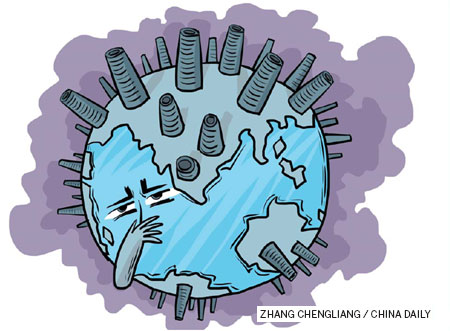

International plan to harness emissions vital in fight against climate change

Chinese President Xi Jinping and his US counterpart Barack Obama recently talked about tackling climate change. Though it is an encouraging step, avoiding climate change requires both China and the US to agree on what to do.

It would have been great if the two nations had agreed to deploy the carbon capture and storage (CCS) mechanism on a priority basis. All the more so as the CCS, despite being the key to tackle climate change, has seen relatively slow progress in deployment. It is important to understand why the CCS needs to be undertaken on a priority basis.

First of all, the CCS alone is not enough to tackle climate change, but is something that is essential to the process. This is especially so as there are no signs of moving away from fossil fuels in the near future. For the coming decades, fossil fuels will continue to be relatively cheap and plentiful. In a world that is hungry for energy, fossil fuels will continue to be burned. Even with essential and major improvements in energy efficiency, cost reduction on renewable energy and a price on carbon, fossil fuels will not be squeezed out quickly enough.

Here's a sobering statistic for anyone who thinks that renewable energy will completely get rid of fossil fuels. Globally, wind and solar energy increased by an extraordinary seven times between 2000 and 2010. But growth in gas and coal-based energy was 40 times that of wind and solar during the same 10-year period. Our priorities have to be based on a proper sense of the scale of the global energy system.

The abundance of fossil fuels is a boon for energy, but a curse for the environment. Unless CCS is used to curb carbon emissions from the coal and gas-fired power plants and a host of other energy intensive industries, our weather will continue to be disrupted. The disruption will undermine food production and damage infrastructure.

The costs of climate damage will probably be greater than the costs of curbing emissions. Unfortunately this cost will get passed on to poorer people and future generations.

The moot question then is, if CCS is so obviously needed, why has progress been so slow and why have governments not given it top priority? The main reason could be that its opponents have been more vocal than the proponents.

CCS is a technology with few friends and apparently no natural owners. Some people don't like the idea of CCS perpetuating fossil fuels. For the sake of the climate, I ask them to be more realistic. Advocates of alternative energies have been smarter at promoting their technologies, partly by suggesting CCS doesn't work. This negativity has slowed CCS deployment, and its opponents are now conveniently attributing that to underlying technical problems rather than to a lack of concerted policy support.

But CCS does work. As the International Energy Agency recently pointed out in its "CCS Technology Roadmap", the component parts of CCS have been in vogue for a long time. Three carbon-capture plants have been running in the US for decades and there is an established CO2 pipeline network in the US of about 6,000 kilometers. A CCS project has been running on a Norwegian offshore gas field for more than 15 years. This is established technology, albeit there is scope for new approaches at lower cost and, as the IEA points out, to integrate the component parts into large-scale demonstration projects.

The IEA also analyzed where CCS is likely to be deployed by 2050. The findings highlight the importance of all major economies pursuing CCS. The IEA estimates that by 2050 the scale of CCS needed in each of these economies will be broadly proportionate to their population.

Meanwhile, the voice of the natural owners of CCS, the gas and coal producers, has been muted. Probably they find it hard to advocate a technology that would significantly increase the costs of using their product, even if CCS is a cost-competitive way of producing low-carbon energy. It would be better if the gas and coal producers could recognize that their products cannot have a long-term future without the CCS.

With such limited support it's not surprising that governments have not had CCS at the top of their agendas for tackling climate change. But I think there is an additional and very significant reason. Embarking on CCS is crossing the climate-change Rubicon. This goes well beyond dipping political toes in low-carbon energy at an R&D scale.

Committing to CCS is, in substance, committing to action to reduce global carbon emissions significantly. We all know this is essential but governments have not yet agreed to do it. CCS along with nuclear and renewable energy must be in the front line of agreed international action to tackle climate change. We need diversification to mitigate technology, cost and security risks.

Just to be clear, this plea about the vital importance of CCS is not to condemn renewable energy. We need both. I'm arguing that CCS is urgent and necessary. I'm not arguing that it's sufficient. We need diversification to mitigate technology, cost and security risks.

What about the costs? A recent report from the UK's Energy Technologies Institute suggests that using CCS would save the UK about 40 billion pounds ($60.5 billion, 46.2 billion euros) a year by mid-century compared with other technologies for meeting low-carbon energy goals. Of course, these are estimates but they show that CCS has considerable potential value.

But how do we get CCS going? It is hard to see the big economies going it alone in a serious way. Concerns about economic competitiveness mean that countries will only act at sufficient scale if they are confident they are acting together. That's why international agreement is vital. And the incentive for the major emitting nations is that their collective action will avoid the worst of climate damage to their economies.

I would argue that getting agreement among the major emitting nations for real and early action on CCS is critical. In the short run, such agreement on CCS could be more important and, though difficult, perhaps more likely than demanding a general agreement among all nations about emissions reduction by 2050.

The major emitting economies of the United States, the eurozone, India and China must work on a stepwise deal where confidence is built over time. Agreement can be developed in a number of areas - technologies for reducing costs; mandatory CCS systems on all new gas and coal plants after a certain date; and a timetable for retrofitting CCS to existing plants. These agreements can usefully be connected to putting a price on carbon emissions and connecting carbon markets globally.

Each country will devise its own policy for implementing CCS. But a combination of regulation, increased R&D support and pricing mechanisms can be used over the next 20 years. The UK, for example, is creating these mechanisms for itself in the current Energy Bill.

Eventually, all the low-carbon technologies, whether renewable, nuclear or fossil, should mature in such a way that market forces, including the cost of carbon, can make the decisions without regulatory intervention.

Everyone who wants to avoid the damage of climate change should be pushing for CCS as a top priority. The IEA concluded likewise and has recently urged governments and industry to ensure that the incentive and regulatory frameworks are in place to deliver upwards of 30 operating CCS projects by 2020 across a range of processes and industrial sectors.

We should continue to fast-track the development and deployment of renewable energy and prioritize the mass roll out of energy efficiency. But as we pass the 400ppm level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the arithmetic of climate change is becoming starker by the day. We can't decarbonize our economies fast enough without CCS. An international rescue plan for CCS is needed.

The author is the chairman of the Carbon Trust, a London-based non-profit company. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

( China Daily European Weekly 07/19/2013 page12)

Today's Top News

List of approved GM food clarified

ID checks for express deliveries in Guangdong

Govt to expand elderly care

University asks freshmen to sign suicide disclaimer

Tibet gears up for new climbing season

Media asked to promote Sino-Indian ties

Shots fired at Washington Navy Yard

Minimum growth rate set at 7%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|