China the last big growth story

Updated: 2013-05-17 08:43

By Andrew Moody (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

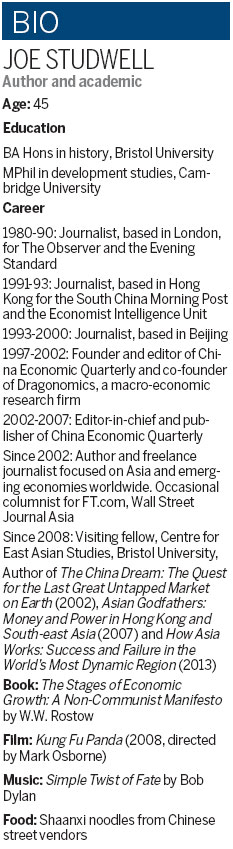

Joe Studwell says it is not by applying free market principles that economies get rich. Nick J.B. Moore / for China Daily |

Agricultural reform, state planning and protection of nascent industries 'led to economic miracle'

Joe Studwell believes China might be the last emerging-nation economic success story the world sees for some time.

The leading Asian affairs author says it is wrong to assume that global development has somehow accelerated and that very soon everyone will soon enjoy Western standards of living.

"Everybody thinks the world is speeding up and after China it will be India and then it will be Africa. I don't see this happening at all," he says.

"China could be the last fast-growth story we see in the world."

Studwell, former editor-in-chief of China Economic Quarterly, has set out his views in his latest book, How Asia Works: Success and Failure in the World's Most Dynamic Region, which is already regarded as one of the major economic titles this year.

In it, he looks at why some Asian countries, such as South Korea and Japan as well as China, have had spectacular economic success and why others, such as the Philippines and Thailand, have not.

One of his central arguments is that it is not by applying free market principles that economies get rich.

Instead, the basis for success has been agricultural development. China's growth story, he argues, began when farmers became market gardeners in the late 1970s.

This gave it a platform for the country to become the manufacturing workshop of the world with the careful guidance of state planning, another Studwell ingredient for success.

"It (agricultural reform) is almost always overlooked. What have you got when you start? You have no capital. You have no technology. What you have got is that - as in any poor country - three-quarters of the population are farmers, and that is what you have got to work with.

"If you ignore that part of the economy - as most developing economies do because they are run by people who live in cities - you have already shot yourself in the foot."

Studwell, 45, was speaking with the spring sunshine pouring into the sitting room of his terraced home in Cambridge, where he is currently working on a PhD.

He says leaders of developing countries often ignore basic fundamentals when they address development issues.

He dismisses those in Africa who currently espouse the view the continent can ignore land reform and manufacturing and develop through retail or financial services.

"It is just rubbish but unfortunately there are people out there saying this. It is being endorsed to some extent by the multilateral agencies and the World Bank support for micro finance," he says.

"Everybody (in Africa) buys a stall and starts selling each other sweeties or washing powder. If these sweeties and washing powder have been made by Unilever, where is this getting you?"

He argues that people are wrong also to see India's development in the same light as China's since it has not been based on land reform but on an IT revolution that has tended to benefit a middle class elite and not the majority farmer population.

"It is the liberation of the posh Indian. It is a facetious thing to say but it is not far from the truth. If you have been to one of the Indian institutes of technology everything is fine and dandy. If you are a landless peasant in Bihar, you are still a landless peasant."

Studwell, who speaks Chinese as well as Spanish and Italian (he lives part of the time in Italy), almost stumbled into a China connection.

After getting a first in modern history at Bristol University, he spent most of the 1980s as a freelance journalist for the Observer and the Evening Standard. His wife, who had studied Chinese at Cambridge, suddenly said she wanted to go and live in China.

The move led to him eventually becoming founder and editor of China Economic Quarterly, which is published by Dragonomics, the macroeconomics research firm of which he was also co-founder.

His big breakthrough came in 2007 with the publication of his second book, Asian Godfathers: Money and Power in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia, which was listed by both BusinessWeek and Wall Street Journal Asia as one of the top 10 business books of the year.

How Asia Works has had a similarly good reception, having been described by the Financial Times as an "important book" that should make people "rethink the glib equation of free-market policies with economic success".

Studwell argues in the book that agricultural reform has been central to all the Asian economic success stories, starting with Japan in the 19th century.

"Japan led the way in the late 19th century with probably the most radical land reform that had been done anywhere in the world at that point," he says.

He argues that the problem with countries like the Philippines is that they only pay lip service to the idea.

"The Philippines still has a comprehensive agriculture reform law in force. They just prolong the thing indefinitely. It has been running for 25 years. It is something you need to do in six months and get on with it," he says.

Studwell insists another essential ingredient of economic success in Asia has been protecting nascent industries and not exposing them to international competition.

He insists both South Korea and China have been particularly successful at doing this.

"The analogy that works best is like the education process of a child and it should not be taken in a patronizing way," he says.

"When you don't understand technology, you don't know about it, you have to learn. What Deng (Xiaoping) said when he came to power was that China had to accept it was a backward country. It took enormous political courage to say something like that."

Studwell makes regular trips to China, often staying months at a time. His Chinese proficiency is mostly self-taught and he says he learns the characters by working out the basis of them.

"I decided I was going to learn the logic of the Chinese language. If you take the characters for silk, for example, they are all to do with twisting, pulling and stretching."

As for China, Studwell believes there is too much of a tendency to see the country's progress over the past 30 years as the easy period of its development process with the next 30 years seen as more challenging.

"I wouldn't say it was easy at all. It has been a huge achievement."

Although he argues that China needs to make further serious reforms including the opening-up of its capital markets, he also says that the country is not at some urgent crossroads yet.

"My expectation is that growth of 7 to 8 percent can continue for another decade and with this sort of momentum, the middle class would be happy with rising incomes, although they will become increasingly frustrated by some of the institutional failures," he says.

"China is not going to collapse if it doesn't do much over the next 10 years, but if they don't do much, the country's potential will be greatly reduced."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 05/17/2013 page32)

Today's Top News

List of approved GM food clarified

ID checks for express deliveries in Guangdong

Govt to expand elderly care

University asks freshmen to sign suicide disclaimer

Tibet gears up for new climbing season

Media asked to promote Sino-Indian ties

Shots fired at Washington Navy Yard

Minimum growth rate set at 7%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|