Gabon's flying fighter

Updated: 2013-05-17 08:42

By He Na (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

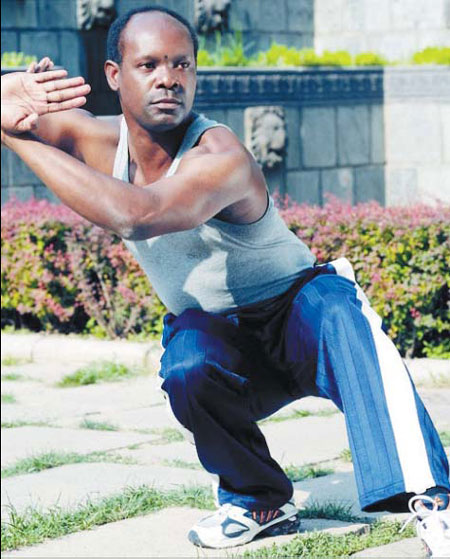

Luc Bendza got a shock at the airport when he realized Chinese people could not fly. Provided to China Daily |

Watching martial arts movies as a boy, Luc Bendza became enamored with china and saved up to fly there when he was 14 before forging success as an actor and cultural ambassador

Children often have big dreams - to be a movie star, a professional footballer or a president - but Luc Bendza's was probably the grandest of them all.

Enamored with Chinese kung fu films as a boy, Bendza wanted to be able to fly like the people he watched on screen.

While flight proved impossible, the fascination with China of the 43-year-old from Gabon did lead him to great things - several international martial arts awards, fluent Mandarin, movie roles and numerous appearances on Chinese television.

And in addition to his acting, Bendza now works as a cultural consultant at China-Africa International Cultural Exchange and Trade Promotion Association in Beijing.

Kung fu movies were popular in Gabon in the 1980s and Bendza was a big fan of them.

"I really admired those people in the movies who could fly. They were able to do anything and fought for justice and helped poor people. I wanted to be a person like them, but when I told my mother I wanted to go to China and learn to fly she thought I was crazy," he recalls.

Bendza began by studying Chinese with the help of Wang Yuquan, a translator working with a Chinese medical team in Gabon.

Sometimes he skipped school to study with Wang, and also called him in the evenings to talk about China.

"When my mother heard me speaking Chinese on the phone she was surprised," he says. "She even took me to see a psychiatrist. But I told her that I had made my decision no matter whether she agreed or not."

Then Bendza opened a video rental store without telling his parents and saved $1,000 to help fund his move.

"In the 1980s $1,000 was really a lot of money. When I presented the money to my parents I could see the surprise on their faces," he says. "After they had confirmed the money wasn't stolen they both sighed deeply with relief."

But still they were not convinced about his plans. What finally swayed their opinion was a phone call from Wang.

"I begged Wang to make the call," Bendza says. "Wang told my parents how serious I was and asked them to give me a chance."

Bendza's parents were both government officials and hoped he would follow in their footsteps. However, they accepted his plans, while also betting with their son that he would soon return.

It was 1983 when Bendza moved to China, when he was 14 years old. There were no direct flights so he was forced to travel through several countries on a long, arduous journey.

"It was a really long and complicated journey for a child, but luckily I wasn't abducted by traffickers," he says.

Bendza's uncle worked at the Gabon embassy in Beijing and picked him up at the airport.

"He was puzzled that I kept looking left and right, my eyes searching for something," Bendza says. "I was looking for people who could fly."

His uncle laughed when he said this and explained that it was movie technicians who made people fly.

"I kept saying no and begged him to find the flying people for me. So he took me to Beijing Film Studio where I saw actors flying, hauled into the air on ropes," he says.

He was disappointed and after just two months in Beijing, decided to go to Shaolin Temple in Henan.

"There were few foreigners in China in the 1980s, especially black people from African countries. Wherever I went many people pointed fingers at me like I was from another planet. But I wasn't annoyed because they were all very friendly," he says.

"The people at Shaolin Temple were really amazing. Although they couldn't fly like in the movies, still their martial arts made a deep impression on me. I told myself I had gone to the right place."

Bendza's Mandarin still was not good, so after less than a year he left the temple and returned to Beijing where he studied Mandarin at university for a year.

After that he enrolled at Beijing Sport University studying traditional Chinese martial arts.

"I stayed at the university for more than 10 years and finished both bachelor and postgraduate studies," he says.

"I really need to thank those teachers who not only taught me Chinese martial arts history and other subjects, but also helped me build a solid foundation for being a real martial artist."

With Bendza's natural aptitude for martial arts and hard work in training, he progressed rapidly and won him recognition from many martial art masters.

"The teacher would put a nail with the sharp end up under your buttock when you were practicing a stance so if you lowered too far the nail would hurt you," Bendza recalls.

On one occasion during winter, Bendza's fingers froze during an outdoor training session and his teacher taught him some exercises to warm them before frostbite set in.

The tough training paid off though as Bendza won several martial arts competitions in China and abroad.

His success also attracted the eye of directors and he went on to play roles in both movies and television series.

Although he was successful, he did not tell his mother. She only discovered how well her son was doing when she read about him winning an international martial arts competition in France.

Bendza began to gain recognition for his achievements in Gabon, but the media there were initially unkind. One newspaper ran a front page cartoon of him standing with two suitcases, a foot in China and a foot in Gabon, but with his head turned towards China. The insinuation was that he had turned his back on his homeland.

"The media used the cartoon to show their dissatisfaction with me," he says. "When I returned to Gabon my mother told me I had to do something to change this bias against me. She took it very seriously."

Bendza organized a free martial arts show as a way of changing opinions and the next day media coverage of him had become more positive.

"When I left, my parents saw me off at the airport and told me they thought I was great. When they said that and my mother hugged me, my tears started flowing and I cried like a baby. That was the first time in 10 years I had won recognition from my mother," he says.

Martial arts have changed Bendza's life and now he says he hopes to promote it across Africa. But his work has also moved away from purely performing toward promoting cultural exchanges.

As a member of the International Martial Arts Association, he organizes Chinese martial arts teams to perform and teach in Africa. "The Chinese teams get a warm welcome from local people whenever they go," he says.

Bendza has been in China for 30 years and witnessed the country's reform and opening-up process. He speaks fluent Chinese, married his Chinese wife in 2007 and has a 14-month-old son. "I have become used to life in China and enjoy being here with my family very much," he says.

A documentary of his life is due to begin filming in February.

hena@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 05/17/2013 page29)

Today's Top News

List of approved GM food clarified

ID checks for express deliveries in Guangdong

Govt to expand elderly care

University asks freshmen to sign suicide disclaimer

Tibet gears up for new climbing season

Media asked to promote Sino-Indian ties

Shots fired at Washington Navy Yard

Minimum growth rate set at 7%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|