China erodes Western monopoly

Updated: 2013-04-26 08:43

By Andrew Moody and Zhao Yanrong (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

Mahmood Mamdani builds an alternative academic career in Africa. zhao Yanrong / China Daily |

Ugandan academic says African leaders have learnt not to put all eggs in one basket

Mahmood Mamdani says the Chinese are doing Africans a favor by challenging Western dominance of the continent.

The leading African intellectual insists it is only Westerners, and not Africans, that accuse China of being a neo-colonial power.

"I think the view depends on location. If I was a Western politician or business person I would probably share that view because the West has had their monopoly here for the last century.

"The big immediate significance of China's role here is that it has eroded this monopoly and from an African point of view, it can only be good."

Mamdani, 66, was speaking from his book-lined office on the spacious campus of Makerere University in Kampala, where he is a leading professor.

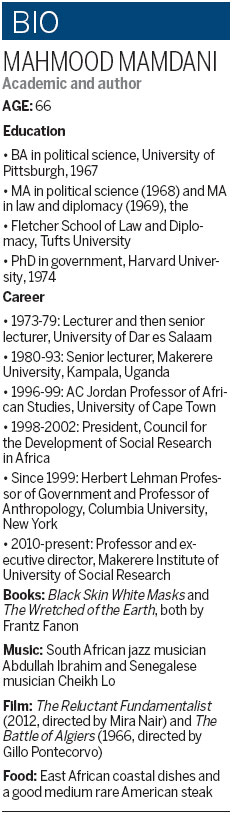

He is best known, however, for his post-9/11 book, Good Muslim, Bad Muslim, which became a surprise bestseller across the world, selling out within 23 days.

"I used to joke that Americans thought it must have been a directory of Muslims, so the next time there was a 9/11 they would know who to avoid. Why would it sell so many copies?" he laughs.

The book put him firmly on the map and in 2008, he came in at No 9 in a list of the world's top 100 public intellectuals published by Prospect and Foreign Policy magazines.

He says he would never have made that list just as an African academic. He is also Herbert Lehman Professor of Government at Columbia University in New York, where he has taught for 14 years.

"That is why I have been able to stand out. If I had just been at Mekerere, forget it," he says.

Mamdani says what he has been able to do as a result of writing Good Muslim, Bad Muslim is bring Africa into the mainstream debate and not just a subject left to African studies, which, he says, is seen as a "backwater field for second-rate intellectuals" in the United States.

"In addressing 9/11, I wanted to bring the African experience into that discussion and debate. In a way it is an odd book because it is not my main scholarship, which is political violence in Africa and the historical formation of the state in Africa, etc," he says.

Mamdani, engagingly urbane and who speaks in carefully crafted sentences, also specializes in the Cold War, which some say is being re-enacted in Africa today with competing Western and Eastern influences.

"I think there are differences. The only sphere the Soviet Union could compete in was in the military area. I think also that African leaders have learnt something from the colonial period and that is to play both sides and not just to go in one camp.

"So if you take countries that are closest to the United States in the strategic sense like Uganda and Ethiopia, they also have growing economic relationships with China. They are not going to put all their eggs in one basket."

Mamdani, also a historian of the Indian Ocean, says China has never resorted to military power to open up trade routes unlike the Western colonialists.

This was evidenced by the great Zheng He voyages to Africa in the early 1400s, he says.

"The Indian Ocean was demilitarized pre-15th century despite the fact that China was the dominant power in the Indian Ocean. Militarization only happened when Vasco da Gama and his fleet came in. Western mercantilism has always used military power to open up foreign trade."

Mamdani doesn't know whether China will always continue to refrain from using military force to get its way.

"I can't predict the future. We don't know what will happen if China goes into the game of competing with the US in all spheres for some sort of global hegemony. We don't really have a sense yet of what international system China wants."

Mamdani, the son of a magazine editor and a mother who was a teacher, is the fourth generation of Indian immigrants to Uganda. He studied political science in the United States and on his return to his home country in 1972 was expelled - as were all Ugandan Asians under the brutal rule of Idi Amin.

He ended up in a camp which happened to be in one of the richest areas of London in Kensington Church Street.

"It was bizarre being penniless among all these really rich people. It was not unpleasant though. I would take the tube every day to go to the colonial archives in Portugal Street and work from 9 am to 4 pm. I didn't have the money for lunch but would have a cup of tea."

He was determined not to pursue a career in the United States and went to teach at the University of Dar es Salaam instead.

"I didn't want the three-bedroom house, the two cars and the three kids. It would have been the end of me. I wanted to go back to East Africa. I was a product of the civil rights movement and I didn't see bourgeois respectability as my future."

He did, however, build an alternative academic career in Africa, which has also taken in stints in Cape Town as well as Makerere.

Married to the Indian-born film director Mira Nair, whom he met when she was shooting on location in Uganda in the 1980s, he now spends every autumn in New York teaching at Columbia.

With Good Muslim and also later books such as Saviors and Survivors: Darfur, Politics and the War on Terror, he has carved out another career as a successful writer, which he says he owes to the late Palestinian writer Edward Said.

"I literally had to learn how to write differently. I sent my first manuscript to Edward, who was a friend at Columbia, and he put me in touch with his editor at Random House, Shelley Wanger, who told me to stop writing like an academic and use the active voice, taking responsibility for my own words."

Mamdani was famously embroiled in controversy five years ago when an article in the London Review of Books appeared to give support to Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe. He was roundly criticized by 35 academics in a joint letter.

He says he was addressing the point that the rise of Mugabe and also Amin in Uganda was on a popular wave of a demand for justice that existed in former settler colonies.

"Rather than anthropomorphizing this phenomenon and reducing it to the person of Mugabe and demonizing him, it was an attempt to address what the issues were," he says.

"The people who try to explain Zimbabwe by demonizing Mugabe were now demonizing me and ignoring the argument. That is nothing new."

Mamdani believes one of the problems in understanding Africa is that many seek to understand it from a Western perspective and the Chinese are as guilty as anyone else in doing this.

"My main critique of the Chinese is that they go to the West for their knowledge of Africa. If you go to African studies associations in North America you see many Chinese there.

"The Chinese see Africa just as a source of primary information but not as location of intellectuals."

(China Daily 04/26/2013 page32)

Today's Top News

List of approved GM food clarified

ID checks for express deliveries in Guangdong

Govt to expand elderly care

University asks freshmen to sign suicide disclaimer

Tibet gears up for new climbing season

Media asked to promote Sino-Indian ties

Shots fired at Washington Navy Yard

Minimum growth rate set at 7%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|