Tempo of time

Updated: 2013-03-08 08:57

By Zhang Lei (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

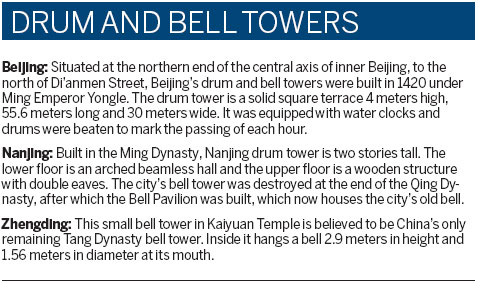

Drum and bell towers at Xi'an, a city famed for the Terracotta Warriors. Provided to China Daily |

Drum and bell towers marked the order of the day for centuries across China - when to wake up, shop or return home

There's a blog in China called Ancient City Bell Tower, which has built a significant and growing following by tweeting the sound of a bell being rung every hour on the hour. Perhaps catering to some longing for the distant past, the site has attracted 440,000 followers by simply updating a public timekeeping system that has existed in China for thousands of years.

Xu Wentian, a researcher at the Chinese Traditional Art Association, says, "This craze is not because people just haven't found a better way to tell the time of course. It is rather a reflection of the fact that the Chinese in general admire perseverance, which many believe is in scarce supply in modern Chinese society."

The drum and bell tower system of timekeeping began during the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) and persisted until the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) when Western clocks made it irrelevant. Its purpose was to keep time and order throughout the country's major cities.

Large cities before the Song Dynasty (960-1279) were protected by an outer wall and within that lay many smaller communities and two markets - the east market and the west market. At the heart of the city was a main drum and bell tower, and at each of the city gates a smaller drum or bell tower. Within each community there would also be a person appointed to keep time using a hand-held drum.

The drums and bells would announce when it was time to wake and begin work, and when it was time to return to your community at the midnight curfew when individual community gates would be locked. They would also announce the opening and closing of the eastern market where luxury goods were sold and the western market where other items, including foreign goods, could be found.

China's most prestigious drum and bell tower is at the heart of the ancient part of Xi'an, a city famed for the Terracotta Warriors.

Although new buildings have sprouted up around Xi'an, many dwarfing the drum and bell towers, they remain the symbol of the city in most people's minds.

Wang Ping, a local resident, says many of her happiest memories growing up were around the city's drum and bell tower area.

"However many modern developments appear and whatever the city becomes in the future, the drum and bell towers in my opinion will never fade in our city's history," she says.

"My parents used to take me to East Avenue right beside the bell tower every weekend to buy daily necessities. It was very crowded there at weekends. I remember watching all kinds of street vendors. With the drum and bell tower looming above your head, you get a surreal feeling that you live in the good, old and prosperous ancient Chang'an city."

Chang'an, renamed Xi'an in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), was the capital of China for 13 dynasties, including the Han Dynasty (206 BC220 AD), which is where the Han Chinese get their name, and the Tang Dynasty (618-907), which is widely regarded as the most powerful period of Chinese influence across East Asia.

Xian's current drum and bell towers were built in 1380 during the Ming Dynasty. Chang'an was long ruined by the end of the Tang Dynasty, but was later rebuilt on a smaller scale and renamed Xi'an. According to historic records, the ancient city that currently sits at the center of Xi'an is an eighth of the size of the original Chang'an.

"Travelers to Xi'an are amazed by the magnificent drum and bell towers and sometimes mistake them for Tang Dynasty heritage, conjuring up scenes in which officials lined up in the morning when the drum and bell towers sounded out, waiting for the emperor to receive them in the royal palace," says Liu Yunwei, a researcher at Shaanxi Folk Art Society.

"Unfortunately the Tang bell tower was destroyed long before the Ming bell tower, but if it is any consolation the bell is a real piece of Tang heritage."

Xi'an's drum and bell towers are China's biggest and best-preserved timekeeping towers, built earlier than their Beijing equivalents. The wooden bell tower stands 36 meters tall on a brick base approximately 35.5 meters long and 8.6 meters high on each side.

It has three layers of eaves but only two stories with a staircase spiraling up the inside. The gray bricks of the square base, the dark green glazed tiles on the eaves and the gold plating on the roof are all Ming architectural characteristics.

The drum tower is about the same height but slightly wider and rectangular in shape.

According to legend, Ming Dynasty Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang, fearing someone might attempt to take his throne, had the country's largest drum and bell towers built as a deterrent.

"Apart from their function of telling the time, drum and bell towers in ancient Chinese feng shui hold strong power over an area," says Liu.

Xi'an's original drum and bell towers faced each other in Guangji Street, at the center of the city, but 200 years later the bell tower was moved to its current position, which is around 1,000 meters to the east. According to legend the bell tower was moved to counter the power of a 1000-year-old turtle monster that was diffusing disease from that point. But official records reveal a much less dramatic truth - that the tower was moved for commercial reasons.

The original bell no longer sits in Xi'an's bell tower. "The Jingyun Bell, which is 247 centimeters tall and 165 cm in diameter at the mouth, was built in 711. It previously stood in Jinglong Temple during the Tang Dynasty and was used in the bell tower. After the tower was moved the bell would never strike out loud again, no matter what people tried," Liu says.

The Jingyun Bell was replaced with a smaller five-ton bell, but still exists in the Museum of the Forest of Stone Tablets.

The function of drum and bell towers across China was to keep time and therefore order. The Chinese idiom 'morning bell and dusk drum' refers to the custom of the guard opening the city gates on the toll of the morning bell and closing them on the strike of the evening drum.

This scene was first recorded in the North and South dynasties, although in reality drums and bells were usually struck in unison.

According to the book Tang Liu Dian, China's first administrative code, issued in the Tang Dynasty, there were originally two drum and bell towers in Chang'an. The city was laid out according to China's strict symmetrical grid pattern, but differed from other cities because it included a large area for aristocrats called the Imperial City and within that the Imperial Palace, which was home to the emperor and his concubines.

On the sounding of the drum or bell, 12 gates around the outer city wall, the gates of the Imperial City and the gates to the Palace City would be opened or closed in a clockwise fashion. The Palace City gates would always open last and close first as a symbol of the emperor's power.

During the Tang Dynasty Chang'an was divided into 108 communities. As was the custom across China, at midnight a person would pass through each community banging a hand-held drum to warn them of the coming curfew. People found outside after the curfew would be punished.

A poem by Li He refers to this scene with the words "rumbling drums uncover a new day, and street drums strike against the moonlit sky".

Xi'an used drum and bell towers to keep time for 600 years, from the early Ming Dynasty until the end of the Qing Dynasty, when Western clocks replaced them.

The ritual was revived in the city in 1997, the drums and bells can still be heard. The city's bell tower rings at 9am, 12 noon, 3pm and 6pm and the drum tower sounds 24 times at 6pm.

The first floor of Xian's drum tower is lined with 25 large drums, decorated with Chinese characters that symbolize good fortune.

Inside the tower there is also a drum museum, which contains drums dating back thousands of years and where a drum show is performed every day at 9am. The ritual begins with 18 fast beats, followed by 18 slow beats. This pattern is repeated three times to make a total of 108 drum beats, a number which signified luck and prosperity in ancient China.

There were originally another 24 drums on the tower's second floor, the largest symbolizing the whole year and the remaining 24 representing the traditional Chinese solar terms. Today only the largest drum survives.

The gate to the drum tower leads into Xian's main food street where many of the city's oldest and best-known restaurants are.

With the completion of a new lighting system last month, the drum and bell towers are now lit up at night and have become a part of the pulsating evening tempo of Xi'an's center.

New lighting isn't the only reminder of the modern world around these ancient buildings. The bell tower sits at the center of a busy roundabout, surrounded by honking car horns and from its roof the view in every direction is mainly modern architecture.

Liu is unhappy with the situation but resigned to the realities of modern life for China's ancient drum and bell towers.

"On the top of the bell and drum tower you used to have a panoramic view of the city, but unfortunately with modern architecture laying siege in every direction it's no longer possible," he says.

"And I'd say the sound of the bell couldn't even be heard more than one block away. Perhaps this is a dilemma, that historic preservation and modern development can never really be in total harmony with each other."

(China Daily 03/08/2013 page26)

Today's Top News

List of approved GM food clarified

ID checks for express deliveries in Guangdong

Govt to expand elderly care

University asks freshmen to sign suicide disclaimer

Tibet gears up for new climbing season

Media asked to promote Sino-Indian ties

Shots fired at Washington Navy Yard

Minimum growth rate set at 7%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|