Lost luster

Updated: 2013-02-01 09:16

By Zhang Lei (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

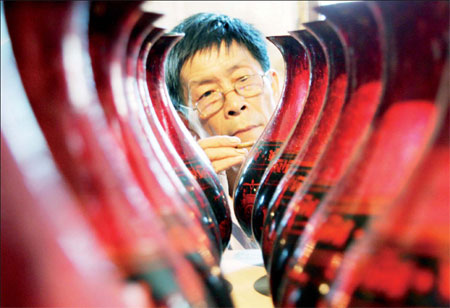

An artisan colors a vase. The mark of quality in such work is a pearl-like polished luster. Zhuo Zhongwei / for China Daily |

Slaughter and destruction following the 13th Century Mongol invasion left China's once proud lacquerware tradition floundering

Lacquerware decorated and varnished with a glossy durable black lacquer is said to have come from Japan but, like many Japanese traditions and customs, has its origins in China. A number of lacquer-painted red bowls from China's Hemudu Neolithic period show that the craft's history stretches back 7,000 years there, long before the invention of silk or pottery.

The lacquer used contains an allergen called urushiol and is poisonous to the touch until it dries, but it has not prevented skilled artisans from China and Japan practicing the craft for generations, using the sap of the lacquer tree as the source of their creation.

The typical Japanese technique, known as maki-e, which means sprinkled picture, starts with patterns drawn using urushiol on the surface of an object, and then gold or silver powder is sprinkled onto the pattern. It is believed this technique spread to Japan from China during the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907).

So why is Japanese lacquerware more highly regarded than its Chinese counterpart? According to Liu Zhenze, a researcher at Beijing Folklore Society, it is a result of invasion, slaughter and destruction.

"The Mongolian invasion of China during the 13th century brought disastrous damage to many art techniques," he says.

"Slaughters at that time decimated the 70 million Han Chinese population, and it is easy to infer from this fact that when the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) began, the art had virtually died out, and new artisans had to learn from the start, so there must have been some blank years in-between.

"Because of this the decorative patterns and style of Chinese lacquerware followed tradition rigidly, centering on over-elaborate and complicated Ming and Qing dynasty varnishing techniques that unfortunately lost all relevance to modern aesthetics".

A quality lacquerware object should have a pearl-like polished luster. On top of this, techniques such as inlaying, coromandel, color painting, etching, wrapping and cover coating are applied.

There are four lacquerware genres in China, the most active being the Pingyao School in Shanxi province and Yangzhou School in Jiangsu province.

Some modern lacquerware crafts people, such as Xue Shengjin, a master from the Pingyao School, are now trying to update the craft. He has looked backward to do this, reviving the lost cover paint technique and expanding the variety of patterns used.

Instead of emphasizing technique over art, he has done the opposite, and urged other craftsmen to stop remaking Ming and Qing dynasty patterns monotonously. He wants young artisans to begin incorporating modern elements into their designs and to use their own creative thinking.

"The Japanese have been quite good in this regard," Liu says. "Their modern lacquerware is rich and creative in its presentation and expression. Their patterns not only reflect Japan's exquisite taste in subtle nuances, but have also stayed in step with the times by embedding concise, fluent and lively elements.

"They have even integrated some very avant-garde freehand and abstract art techniques into traditional creations, so that most modern people can find them attractive."

Besides its use for decorative objects, lacquer was also used as a protective coating on furniture. Liu believes the fact that China stopped using it for this mass-market practical use is another reason for its level of craftsmanship falling behind Japan's.

Most surviving ancient Chinese lacquerware objects are practical items, such as utensils. More modern craftsmen receded from this and concentrated on decoration. By contrast, Japanese crafts people have aimed for both practical use and beauty combined.

"Lacquerware plays an import role in the daily life of many Japanese," says Liu.

"You can find it in architecture decorations, furniture, presents and tableware, and Japanese artisans have been working hard to open up new areas for its use."

Lackluster duplication by Chinese artisans has led to a shortage of professional talent and a stagnant training system.

Training is mostly one family member teaching another, and most artisans have neither the ability nor the environment to modernize their work.

Chinese lacquerware artisans are mostly technicians rather than artists, and if this situation continues the craft will lose its "soul" he says.

But there may still be the chance of a renaissance in the craft in China, he says.

"If some day we have no distinct line between experts and artisans, as in Japan, Chinese lacquerware may have the chance to regain its lost glory."

zhanglei@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 02/01/2013 page26)

Today's Top News

List of approved GM food clarified

ID checks for express deliveries in Guangdong

Govt to expand elderly care

University asks freshmen to sign suicide disclaimer

Tibet gears up for new climbing season

Media asked to promote Sino-Indian ties

Shots fired at Washington Navy Yard

Minimum growth rate set at 7%

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|