As the Chinese consumer goes...

Updated: 2013-01-04 09:49

By Diao Ying (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

Oxford historian Karl Gerth says the everyday choices Chinese consumers make will influence everything from Chinese politics to the world's environment. Patricia Thornton / for China Daily |

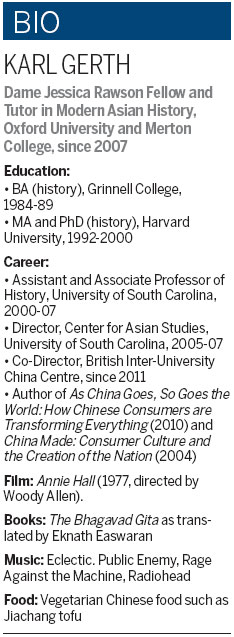

Karl Gerth has spent a quarter of a century learning about China, but is wise to how little he still knows

When Karl Gerth first went to China in 1986 he was a college student with barely enough money for a pizza and a six-pack of beer. But in the eyes of his Chinese classmates he was a rich American with a lot of money to spend.

Gerth, now an Oxford historian, also remembers that he was surprised with the absence of cars in Nanjing, where he stayed. There was no noise and no traffic lights, he wrote. China has changed a lot since then. It is now the world's largest maker and seller of cars and consumer of beer, among many other things.

People in the West advance many reasons to explain why China has been so successful economically, the most obvious and most widely cited being Deng Xiaoping and his reform and opening-up policy. Gerth feels that is not enough.

"These are facts and these are true. But we already know it," he says. Given the country's size and the pace of change, "you can say anything about China and it is kind of right". There may be simple answers to a lot of complex questions, and they all have some truth in them, but they do not explain things thoroughly or give a clue about what we will know next, he says.

Gerth now teaches at Merton College, Oxford. His office faces the river, where he rows for two hours early in the morning. Books, from business history to literary classics, dominate his office. A drawer has a selection of Chinese tea, coming from his trips to China, including a mix of pu'er and ginger and tieguanyin, or "iron Buddha".

As a historian, he believes history is shaped by people at the bottom as well as those at the top, and consumption drives society as much as production. His latest book, As China Goes, so Goes the World, is his attempt to explain China from a different perspective: how the everyday choices Chinese consumers make will influence everything, from Chinese politics to the world's environment.

When he was doing research for the book, Gerth was all eyes and ears; he talked to people in small shops and in supermarkets, and he observed the surroundings. Doing that, it became clear to him that Chinese are driven by the "desire of having things, better things, and more things".

Studying China through the eyes of consumers is not necessarily the best approach, Gerth says, but it helps him to discard irrelevancies and reach proper conclusions. The idea of consumerism is that people communicate who they are through things they buy in the marketplace. In a consumer culture, people's identities are shaped by their gender, accent and education, as well as the things they use. For example, the person who drives a gas-guzzling Hummer is not the same as someone who owns a fuel-efficient Prius.

The difference between China and the West in adopting consumer culture is its speed and scale. People in the West may have learned to ask for "Coke" instead of asking for "sugar water" since World War II, and Coca-Cola only opened its first plant in China in 1981. China has its own characteristics, but Chinese are not from Mars, Gerth says. Because of China's size and the pace of change, a lot of things that happen there may have a different level of intensity, he says.

Such circumstances shape how consumers see themselves and will influence policymakers at the top, too. The Chinese government has made it its priority to drive domestic consumption. That is no easy task, and in doing so it needs to take heed of social problems. People talk about Chinese being thrifty, Gerth says, but the truth is that apart from the richest ones, an average Chinese needs to save enough money for housing, healthcare, and their children's education before they can really open their purse and consume, regardless of advertising blandishments.

This means that the policymakers have to create a big middle class, and Chinese companies have to move up the value chain. "The logic of reform is an unfolding process; circumstances decided that they have to take a certain way, not others," he says. Deng Xiaoping said that the Party needs to cross the river by feeling the stones. "The problem is that once you have left the stones, it disappears," Gerth says, "You stop in the middle and there is no going back. You have to keep moving."

Seeing things from the perspective of consumption also reveals the conflicts in some issues such as the environment. Western governments and companies want China to consume more. At the same time they criticize it for polluting the environment. These two things contradict each other. If the Chinese eat as much meat as people in the West do, many species may become extinct; or if the Chinese drive as many cars it will be a disaster for the planet.

Some critics say Chinese society is dominated by materialism, but Gerth disagrees. Consumption may not always lead to something bad. While consumers seek pleasure, they also gain other things, a different view of the world or a new approach to life. For instance, when Chinese travel, they also experience adventure and see other parts of the world. When they shop for a luxury handbag, they are buying a meaning for life. In five or 10 years, once they have gone beyond this level, things will change. As with consumers in the US or Europe, they may start to pay attention to the environment and fair trade. In fact, that is already happening in China now.

Meanwhile, Chinese brands are emerging on the global stage. They have to do so to get a bigger share from the global market.

"As it is in American football," Gerth says, "the best offense is defense."

Lenovo, the computer company, bought the personal computer division of IBM. And Huawei, one of the world's largest telecommunication companies, is establishing itself in terms of its price and technology. Like Sony and Hyundai, Chinese brands are going to improve the life of consumers elsewhere. They may make things cheaper and easier to use, as they did in manufacturing. There will be many successes as well as failures, and Chinese companies have no alternative but to try, Gerth says.

Many governments are still cautious about things from China. Talking about the recent US congressional report on keeping Huawei out of the US, he says that apart from security issues it is fundamentally about whether you want Chinese investment or not.

When he wrote the book, Gerth says, he spent six months in the mountains of South Carolina with no human contact. It was great to spend so much time on a project and bring it as near as possible to perfection, he says.

Gerth says the book is as much an academic quest as a way to explain his personal experience in China over 25 years. He goes to China frequently and experiences many of the changes personally. He has traveled to remote southwestern areas such as Lijiang in Yunnan province that are blessed with tranquility and night skies full of stars. Such places are now packed with tourists and Western-style bars, he says.

Now, after five years working on the book, he feels he has an intellectual appreciation of what is happening in China. Nothing that happens there can surprise him, although some things disappoint him, he says.

The late Harvard historian John King Fairbank once said that learning about China is like drawing a circle. Inside it is knowledge, and outside it is ignorance. Fairbank said that he often felt that as his knowledge about China grew, so did his ignorance. Gerth says he feels the same.

"The more I know, the less I feel I know. And that makes me humble."

diaoying@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 01/04/2013 page32)