Darkness' bright side

Updated: 2012-12-14 09:41

By Liu Wei (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

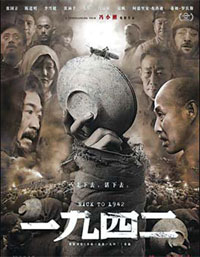

Author Liu Zhenyun reveals one of the darkest historic events in his novella Back to 1942, the film adaptation of which is in theaters. Jiang Dong / China Daily |

When he was doing research for his novella, Liu Zhenyun discovered many survivors of Henan province's famine 70 years ago had forgotten about the disaster

Writer Liu Zhenyun had an incredible discussion with his grandmother in 1990, when he returned to his hometown, Henan province's Yanjin. "Do you remember 1942?" he asked. "What happened in 1942?" his grandmother asked. "People starved to death," Liu said.

"People starved many years. Which famine are you talking about?" she responded.

Liu was doing research for a book chronicling a century of disasters in China, when he stumbled upon a rarely discussed catastrophe.

A famine killed about 3 million people in Henan in 1942.

He was shocked to discover many survivors, like his grandmother, have forgotten about the horrific event.

His conversation with his grandmother features in his 1993 novella Back to 1942 but isn't in the namesake blockbuster film now in theaters.

Celebrated director Feng Xiaogang adapted the book into the 147-minute film based on a script written by Liu.

The film grossed 200 million yuan ($32 million; 25 million euros) within a week of its Nov 29 premiere.

Liu recently published a book that includes the original novella and the film's script.

"The book shows how something seemingly un-filmable became a film," the author says.

Liu's novella is more like an investigative report than a story. There's no protagonist or central plotline. The work instead comprises sketches of six different groups of people during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-45).

Millions of famine refugees trekked from Henan to Shaanxi in 1942, as the Kuomintang government allied with the United States to fight the Japanese.

Time magazine reporter Theodore Harold White witnessed and documented the refugees' plight, while foreign missionaries preached to the starving.

It's virtually unheard of to base a film on six groups of people who barely interact.

Liu recalls few of the experts he and Feng visited in 2002 believed it was possible to adapt the book to film.

Liu later squatted beneath a tree and told Feng: "People are used to doing easy things. But difficult endeavors require much more."

Liu insisted all six groups appear in the film because - beyond such surface causes as locusts and drought - people were the tragedy's source.

"Politicians, the national army and the Japanese invaders all manipulated the natural disaster for their own interests, despite the sufferings of millions of ordinary people," he says.

As "dumb people, who don't take shortcuts", the two started a three-month journey through Henan, Shaanxi, Chongqing and Cairo - the places their characters trek.

They were inspired by what they felt and observed.

The duo felt too tired to keep talking, despite having full stomachs and no luggage.

"Think about the refugees, who practically carried their homes on their backs in extreme hunger. They wouldn't talk much," Liu says. "So the film's dialogues are very short."

They interviewed many people along the way. One man told Liu he was the only survivor in his family and felt guilty.

"He told me: I fled because I wanted my family to survive, but they all died. So, what was the point of me leaving home? If I had stayed, at least we would have died together," Liu says.

He was most impressed by the fact many survivors had forgotten the disaster, while the youth hadn't even heard of it.

"People forget something only if it's unimportant or too commonplace," Liu says.

"Henan has suffered famines since the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770-256 BC). They've always had people who starved to death, sold their wives and ate their compatriots.

"I found something peculiar about our people - when disasters happen frequently, they forget or dispel them with black humor."

Black humor colors the film.

A woman refugee volunteers to marry a young man, because the marriage would give him a wife, so he'd have something to sell. It is win-win: The man gets money, and the woman finds someone to feed her.

Such scenes have put audiences in stitches, which Liu takes as a compliment.

"I'm intrigued by the refugees' humor and convey that to audiences," he says.

"The great writer Lao She once said he wanted to write a tragedy filled with laughter. I think that's the real tragedy. When something really horrific happens, there must be something laughable in it."

He's aware many viewers stay in their seats in silence after the film ends.

"I take both their laughter and silence as signs of the film's impact," Liu says.

"The novella and the film are like needles that prick a numb body."

The script ends with an old survivor picking up a girl on his way home and taking her as his granddaughter.

Flowers suddenly blossom around them as they walk.

The scene does not appear in the film because the special effects don't match the film's grinding tone. But Liu believes in warmth and beauty deep in his heart.

"We present human nature's darkness in the novella and film, but darkness only becomes so when contrasted with brightness," he explains.

"Even in the darkest times, I believe in the kindness of ordinary people - even if it's small and fragile."

liuw@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 12/14/2012 page30)

Related Stories

A true picture of turning Liu's fantastic fiction into Feng's film 2012-12-14 09:41

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|