Changing Chinatowns

Updated: 2012-11-16 11:10

By Cecily Liu (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

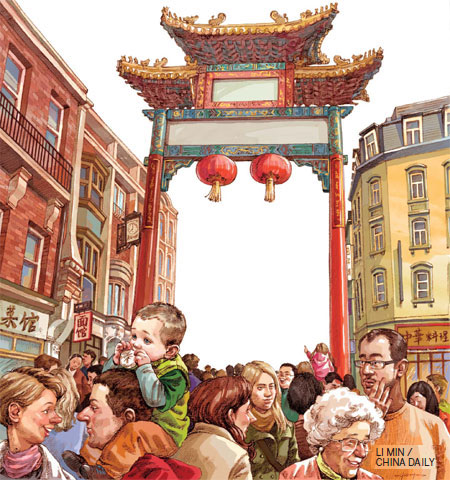

Chinatowns in Europe reinvent themselves to stay relevant to migrants, locals

Times are changing and so are the Chinatowns across the world. Starting off as ordinary trading outposts that attempted to satisfy to the culinary needs of overseas Chinese communities, these towns have evolved to become major soft power assets and representative symbols of the modern and resurgent China.

No one knows it better than Kelly Su, who is having the time of her life. The 18-year-old music teacher at a Chinese community center in Liverpool, UK, not only enjoys the comfort of financial freedom but also finds enough time to pursue her favorite passion of strumming the yangqin, a Chinese stringed musical instrument.

"When I finished high school this summer, I first thought of going to university. But I decided to be a teacher at Pagoda Arts as I felt it would better suit my music career," she says. Playing yangqin is her unique way of connecting with her roots with China.

Su and her family came to the UK eight years ago from Guangdong in China hoping to find greener pastures. Like most of their peers, the Su family also initially landed up in the British coastal city of Liverpool, where Su's father later found employment as a chef. Britain's Chinese population is estimated to have grown over the years to 650,000. Liverpool has the distinction of having the oldest Chinatown in Europe.

For most of the immigrants from China to the UK, the Chinatown in Liverpool was not just a second home where they could find familiar people, food and culture. It was also an extended community that offered help and solutions to most of the major problems faced by the new immigrants.

"I couldn't speak any English, my classmates teased me and hid my things. Back then, I dreamed about going back to China every day," Su says.

Without the financial means to rent a house of their own, Su, her mother and brother stayed with relatives while her father worked in Sheffield, a city about 80 miles east of Liverpool.

"My father used to come home every day at about midnight and rarely spent any time with the family. Life was a constant struggle," she says.

Though her work at Pagoda Arts often entails long hours, particularly during school-term breaks, Su is not complaining.

|

Kelly Su, 18, is a music teacher at Pagoda Arts who came to Liverpool eight years ago with her family. Zhang Bin / China Daily |

"I realized very early on that there is no substitute to hard work especially if you want to be successful. For me it was also imperative, as I did not want to be trapped in the catering business. I wanted to do something different," she says.

Recollecting the interactions she had with the community leaders in Chinatown, Su says that the unanimous opinion of most of them was that she should learn Mandarin at the local language school.

"My parents have asked me to study Mandarin so that I can find a good job. I believe them because I can see China has become a rising power internationally, and I've been invited to give talks on China in local high schools," she says.

Su is just one of the generations of Chinese diaspora, who have grown up with good education and ambitious dreams, and are also part of the new generation who are heralding change.

Early days

Chinese immigrants started coming to UK in a big way in 1866 after the Blue Funnel Shipping Line started regular steamer services between Shanghai and Liverpool for shipping silk, cotton and tea from Shanghai to Liverpool.

The early migrants stayed in the boarding houses set up by the shipping company in Liverpool, which later became the cornerstone of the first Chinatown in Europe. Though many of these settlers started their own businesses they maintained a low profile due to their low social status. Wages paid to these Chinese workers were often far lower than those paid to the average English worker.

|

||||

In 1945 more than 1,000 Chinese seamen were repatriated against their will, of whom more than 200 had married British women, and hence had legal rights to stay.

Though a plaque erected at the Pier Head in Liverpool indicates that such incidents would not be allowed to happen again, the second and third-generation Chinese migrants feel that, unlike their predecessors, it is important for the community to make itself known and heard.

It is precisely this ethos that have led to the establishment of the Liverpool Chinese Business Association in the 1990s, initially to combat street crime in Chinatown. "Liverpool's Chinatown area experienced a high level of car crimes in the 1990s, because the surrounding areas were residential, and lots of children had nothing to do," says Alan Seatwo, the current chief coordinator of the LCBA.

What the LCBA has done is to give Chinatown and the Chinese community a voice that can be heard, he says. "We have given the community a focus and worked with local police and social service providers to solve many problems encountered by Chinese restaurants, shops and supermarkets," he says.

The LCBA also worked with the Liverpool government to facilitate a twinning arrangement between Shanghai and Liverpool to rekindle the past ties between the two cities. To commemorate this twinning, Liverpool's Chinatown received an arch made in Shanghai and transported to the UK piece by piece in 2000.

"The twinning with Shanghai has captured the city's imagination," Seatwo says. With 200 dragons engraved onto the marble arch coated in a mixture of gold, red, green and yellow, the arch has became a symbol of Liverpool's Chinatown, and put it on the tourist map.

LCBA, which is staffed by volunteers, has risen to be an important business body in Liverpool by providing advisory services to many British businesses keen on expanding linkages in China.

"We also helped the Liverpool government set up an exhibition area during the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai. As China's economy grows, its links with British businesses will also grow, and we are very proud to be a bridge between the two," he says.

Seatwo initially came to Liverpool in 1987 to study advertising at Liverpool John Moores University. "Back then, everyone in the Chinese community worked in takeaway restaurants."

To support himself financially, he worked part-time at a Chinese restaurant. Finishing university classes at 4.30 pm, he would typically work from 5 pm till almost midnight.

One of the projects he helped initiate in cooperation with the Liverpool local government two years ago was the Eat Right, a certification given to restaurants that reduce the amount of salt and monosodium glutamate used in cooking. It was intended as a way to help Chinese restaurants adapt to the demands of increasingly health-conscious British consumers.

"Chinatown's restaurants need help to stay competitive in today's market, but they also need to change their mindset and improve the quality of their food and services," Seatwo says, adding that some of the changes to food quality are already being embraced enthusiastically.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|