Through the looking glass

Updated: 2012-11-09 10:08

By Gerard Lyons (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

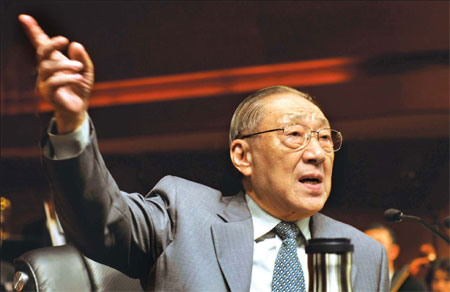

Li Lanqing's book, rich in detail and anecdotes, is an insider's guide to China's opening-up. Peng Nian / for China Daily |

First-hand account traces the remarkable story and the events behind China's opening-up policy

Breaking Through is a fascinating book about China. It provides the author's personal and first-hand account of the period in the late 1970s to the early 1980s when China began to open up its economy to the outside world. This is, without doubt, one of the most significant periods in recent history, not just for China but also for the entire world.

There are many books about China but this one is different, largely because the author Li Lanqing occupied senior positions throughout this period. His first-hand experience is imprinted throughout the book, from when in 1958 he accompanied China's first domestic car from the factory to Beijing for the Party leadership to see, to his time in 1983-86 as vice-mayor overseeing economic change in Tianjin, now one of China's wealthiest cities. Eventually he joined the Party's central leadership. This is an insider's guide to China's opening-up, rich in detail and anecdotes.

The pace and scale of change in China after the opening up has been dramatic. Yet, as Li Lanqing makes clear, back then its catch-up potential was huge. The "cultural revolution" (1966-76) left China with many scars, not least a poor and undeveloped economy. In 1955 China accounted for 4.7 percent of global GDP, by 1978 it was only 1 percent. While others had moved on, China had gone back. Difficult times were deeply etched upon the Chinese.

The years of 1972-73 saw China restore diplomatic ties with many Western nations. In February 1974 Chairman Mao Zedong spoke of the "Three Worlds", with the US and the Soviet Union in the first, the developed countries in the second, and the developing countries in the third. There was little doubt over China's ranking and no clue that things were about to change anytime soon.

Yet, as Li indicates, the end of the Gang of Four in 1976 spawned the dawn of China's national rejuvenation. In the author's minds, one person was central to this: Deng Xiaoping. As China's leaders came to terms with the poverty of their people and the yawning gap between them and the West the enormousness of the task and the "race against time" to develop as Deng called it became clear.

The major issues before opening-up are brought to life in this book. One was the need to justify policy in the context of dogma. In May 1978, the Central Party School released a landmark article by Hu Yaobang, "Practice is the only criterion for judging truth" as he tried to address the legacies of the "cultural revolution". This caused controversy. Deng stood up for it at a critical juncture. Being bold, visionary and insightful, he seized a historic opportunity. Yet, despite the opening-up policy, it was not until 1992 that the establishment of a socialist market economic system became a clear policy decision. It still took some time to win the domestic debate.

International influence was also the key. China had to recognize how other countries had changed. The late 1970s was a time when China's minds were really opened to the outside world. We read of Deng's autumn 1978 trip to Japan and his journey as the first Chinese leader to visit the US in January 1979.

The book has many in-depth and insightful descriptions, which shed light on how thinking and policy evolved. One is the story of China's first official overseas economic delegation, led by Vice-Premier Gu Mu. The delegation spent two months visiting France, West Germany, Sweden, Denmark and Belgium in 1978. They were stunned by how far behind China was. Just as importantly, they saw the willingness of others to invest in China, rightly concluding it was possible to utilize foreign investment to spur domestic investment and that China needed advanced foreign technology. All this fed into a frenetic policy debate.

A 20-day brainstorming meeting in Beijing in July 1978 reflected on how two defeated nations such as Japan and West Germany could rise to their feet so soon. The momentum was with those who wanted to open up.

Education was both an important driver and consequence of the opening-up program. On boxing Day 1978, 50 visiting scholars took off from Beijing for two years of study in the US. Not only were students about to learn more overseas, but at home too. In 1977 China did not have enough paper to print exam papers for its 273,000 college students. By 2007 enrollments had risen to 5.7 million.

There are also some amusing moments in the book. One is the story of the barbers. A hair-cut appears unimportant compared with food, clothing, shelter and transport, but in the 1970s it loomed large as a challenge. To cut long lines at barbers a piecemeal wage system was introduced: barbers were paid on the basis of per head cut. Soon, there were no lines. Instead, another problem arose, as quality suffered at the expense of quantity. As the author says, "When one of the 'victims' came to my office to complain, I immediately knew what he wanted to say. His hair was cut in such a fashion that he appeared to be wearing a wok cover on his head."

There is so much else in the book, from the birth of special economic zones in 1984, to the adoption of new words such as bonus, feasibility studies or even firing, to the hard bargaining over 15 years to join GATT, with the US and Chinese negotiators accusing the other country of being robbers.

Yet even though this is the author's first-hand account, the abiding image of this book is how one man, Deng Xiaoping, seized the initiative and drove forward the opening-up of an economy. Although in recent years there is a wider and perhaps more critical perspective on Deng's role there is no doubt in this book that he is the hero.

The author tells us that his maxim is something that was said to him after he joined the central leadership in 1992. It was said to him by Deng and one has to say it is as relevant for China now, as it was then, and it is the lasting memory of this book, "We have got to reform and open up; otherwise we are doomed."

The author is chief economist, group head of global research and economic advisor to the board at Standard Chartered Bank.

For China Daily

(China Daily 11/09/2012 page30)

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|