A step down the ladder

Updated: 2012-09-28 10:31

By Giles Chance (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

To continue generating prosperity, nation must reform its market and accelerate innovation, among other tasks

Since Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations (in 1776, the same year that the 13 American colonies of the Commonwealth declared their independence from Britain), economists have tried to understand the factors that make a country's economy more competitive. It's an important question, because a country's prosperity, and the material comfort of its people, depend on improvements in economic productivity. Given that there are only 24 hours in a day and 365 days in a year, and given no huge changes in resource endowment, it's just the gains in each person's productivity that make the country richer.

A Chinese farmer becomes much more productive when he moves from the field to work in a factory producing good-quality clothes because he goes from using traditional, inefficient equipment to working with new machines and many other workers in an efficient factory layout that sells its products to appreciative markets.

For economists, though, the big question is whether a country's increase in productivity derives just from using more machines and from additional labor, or if there is something else. The "something else", called total factor productivity, derives from improvements in combining machines and workers in new and better ways. In broad terms, these new ways derive from improvements in technology. All advanced economies, such as the United States or Japan, derive most or all of their increased prosperity from improvements in total factor productivity, not from adding more workers or more machines.

Every summer since 1997, the World Economic Forum has released its survey that ranks countries and regions against each other for economic and business competitiveness. The WEF Global Competitiveness Survey, as it is known, has become increasingly sophisticated with its tables of data now running to more than 500 pages. It is a detailed and successful attempt to see where each country stands in terms of national wealth and to understand how prosperity is created.

Since 2000, China has progressed up the Global Competitiveness Index faster than any other country. A decade ago, in 2002, China ranked 47th, behind Uruguay and ahead of Panama. In 2012, China ranked 29th, behind Ireland and Brunei, and ahead of Iceland and Puerto Rico. Over the same 10-year period, Singapore, Malaysia and Japan have risen in the GCI, while France, Australia, South Africa, India and Brazil have fallen significantly. But in 2012, China fell by three spots from its position the previous year. It now occupies the same position in the GCI that it did in 2009. Does this mean that China's competitiveness has stopped improving since 2009 and that its growth in national prosperity will slow?

The GCI calculates its results on three main metrics: basic requirements (such as infrastructure, health and primary education); efficiency enhancers (such as market efficiency, higher education, financial market development and technological readiness); and factors of innovation and business sophistication (such as innovation and the availability of scientists). The first and second metrics correspond roughly to productivity gains by additions of labor - more workers - and capital, in the form of machinery and infrastructure, and bank loans for working capital. The third metric, innovation and improvements in technology, focuses on gains in total factor productivity. The top 20 economies in the GCI - headed by Switzerland, Singapore, Finland, Sweden and the Netherlands - all have high scores on the third metric - innovation and business sophistication. They are all generating a lot of total factor productivity.

When you consider where China was in 1980, of course it's remarkable that the country, with its huge population of poor farmers, could reach the giddy heights of the top 30 in the GCI less than 30 years later. But China's work is not yet over. Millions of poor Chinese remain to be lifted out of poverty, while China's well-known demographic problems, which cannot be quickly changed, compound the problem. China must go on generating prosperity. Of course, it can be argued that the GCI is a relative measurement and that China's national prosperity is being compared with other countries that are not standing still, but moving ahead. But China's score in 2012 was a touch lower than in 2011 and 2010. It's going the wrong way.

China gains its position of 29th in the GCI by scoring well on the first and second metrics. It does well on measures like airline seat availability, the quality of railroad infrastructure and enrollment in primary school education. But its business environment still lags that of advanced countries. It also scores badly on its total tax rate for businesses, on trade barriers, as well as in the difficulty of starting a business and import penetration. Its labor market practices are a step behind, and its weak financial market development handicaps small and medium-sized enterprises in their search for business financing. But it's in the areas of technological readiness, business sophistication and innovation that China has to make big changes in order for its competitiveness to continue improving.

Weak competitive advantages and the poor quality of local suppliers, of production processes, of marketing and management are all holding China's economy back. China scores high on its capacity for innovation, but not quite as well on its quality of scientific research and on its availability of scientists and engineers.

The message from the 2012 GCI survey is that if China wants its prosperity to continue growing, it needs to continue to open up and reform its economy. It can't stand still. In February, China's Development Research Center of the State Council, in conjunction with the World Bank, published its report China 2030 that indicates the way for continued improvement in China. The path is not easy, but at least it's clear: The nation must implement market-based reforms to strengthen the economy; accelerate innovation; go green; expand opportunities and social security for all of its citizens; strengthen the tax base to increase government revenues; and improve China's relations with other countries and promote openness.

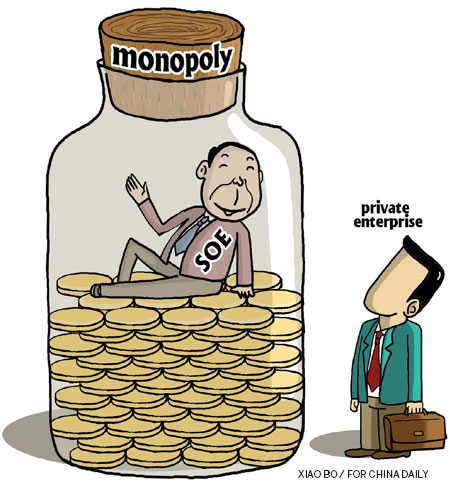

When the report China 2030 was published, it aroused strong negative feelings inside some of China's dominant, monopolist State-owned companies which are happy with the way things are. Too many of China's most talented students aim their ambition after graduation at joining a large State-owned enterprise. To be sure, China needs to recruit some of the best students to staff its ministries and SOEs, but more students from China's better universities need to be attracted to small and medium-sized companies by the promise of an exciting, worthwhile career with significant financial reward. China has to improve the environment for startups and small businesses by allowing better access to reasonably priced finance and providing a legal environment that protects an individual's ownership of a brand-name or a private company. To reach its goal of providing a decent life for all Chinese, China must encourage and support private enterprises.

The long shopping list in China 2030 requires determination and commitment to execute. But the alternative is economic and social stagnation. China's position in the Global Competitiveness Index provides an annual snapshot of the change in China's national prosperity - a valuable service. But will China's position in the GCI of 2022 be higher or lower than it was in 2012?

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily 09/28/2012 page10)

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|