Golden haul with a hollow ring

Updated: 2012-09-21 13:30

By Zhengxu Wang (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

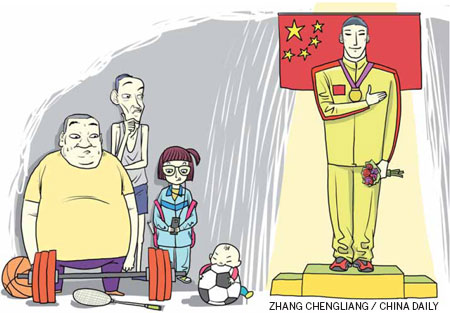

The country's Olympic success highlights the growing gap between elite athletes and the public

After a summer of frenzied excitement as it hosted the Olympic and Paralympic Games, Britain is about to embark on a period of reflection.

The British media has for once been united in its praise and patriotic fervor, but now its focus will turn to a forensic examination of whether the British government can live up to its promise of a lasting legacy, the reward for its 9 billion pound (11.2 billion euros) investment in the Games.

Debates around legacy in the Britain center on encouraging greater public participation in sport and leisure activities - particularly among those toward the less well-off - in order to foster a healthy, productive population and minimize the burden on the National Health Service.

In China, the end of the Games marks an opportunity to publicly bemoan just how disconnected sport is from ordinary Chinese people.

This may appear a curious lament when the final medal tables from London are considered. China enjoyed extraordinary success this summer on the back of stellar performances in Beijing four years ago, coming a clear second in the London Olympics medal table and winning nearly three times the number of Paralympic gold medals than its nearest rival.

Yet underneath the gold luster, the sad truth is that sport in China remains a government-managed activity far removed from people's daily lives, unlike the situation in Britain, the US and Europe.

The importance of competitive sports is embedded in national history. When China first emerged from social disintegration and underdevelopment - having been ravaged by colonization, a failed republican revolution and the ensuing warlordism, the Japanese invasion and civil war - the State took it upon itself to build a "strong and prosperous" nation.

A State-led developmental system was created by following the Soviet model. Sport as an arena in which to showcase the improvement in people's living standards and general health and fitness was vigorously promoted.

Besides training physical-education teachers to identify the most talented schoolchildren, the state's sports-commission system carefully selected and trained a very small number of athletes to compete internationally.

The Cold War accentuated this production-line approach. Sport came to be seen as a power game between East and West. China believed it needed to succeed at sport to stake its place in the new world order.

What resulted was a sports state that exerted tight financial and political control over a wide range of sporting disciplines, with the goal to identify athletes when they are very young, enroll them in a rigorous training system and put them on the international stage to compete for the honor of the nation.

This system can be partially justified by the precarious international environment in which the young republic found itself, by the scarcity of resources available for sports development and by the public's nationalistic passion for China to find its own identity.

In the late 1950s, Chinese table tennis players began to win world titles. Very soon, Chinese athletes were able to set new world records in events such as weightlifting. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the women's volleyball team won three world titles in a row.

At the same time, China solidified its position as the leading sports power in Asia. At the 1982 Asian Games, China collected the largest number of gold medals, unseating Japan from the top of the table.

At the 1984 Olympics, China's maiden appearance at the event resulted in fourth spot in the medal table, a great surprise to China and the world alike.

The State was responsible for these successes; without a strong government hand, they simply would not have been possible given China's overall level of economic and social development. The relatively weak standing of India in international sport is a telling contrast.

But times have changed. What was desirable in the past must be reviewed. An institution that is out of date must be reformed.

The great irony of sport in China is that while its national team can compete head on with the US for the accolade of top Olympic power, public participation in sport and leisure activities languishes at a low level.

School students in China are required to participate in a gymnastics session every morning, following pre-recorded steps broadcast from a loudspeaker - the so-called guangbo ticao session. Beyond that, they only have two hours of PE lessons every week.

After school, while some children elect to stay around for an hour of basketball or table tennis, the majority will return home to continue with their coursework or attend evening tutorials. The academic pressure and the competition for university places are simply too intense for a sporting culture to develop in school.

By contrast, in schools and universities in Europe and North America, many sports clubs run by the students themselves involve students of every skill level. It is no surprise that with such a broad base of participation, the US and Britain can form national teams that win medals at the Olympics.

In fact, student athletes of my current university, the University of Nottingham, won several medals for Team GB at the London Olympics, making Nottingham the second most successful British university at this year's Games.

The university where I studied for six years, the University of Michigan, regularly supplies the US national team with a large number of athletes. In London, US athletes currently studying at Michigan won six gold medals, two silvers and one bronze.

A recent article on US school sport in The Guardian newspaper in Britain quoted a US sports-psychology expert as saying: "Sport is like a religion here and in some parts of the country it drives everything from the local community all the way through schools and colleges to state government."

There is no need for the existence of a Chinese-style provincial sports bureau to train these athletes. Day to day, they study as other students do and train only after classes.

Chinese adults meanwhile very rarely take up sports in their spare time. Add improved nutrition and increased carbohydrate intake, long working hours and all the stress and anxiety that comes with a rapidly developing society, and you have a rapidly growing health crisis, with rising obesity, cancer and cardiovascular-diseases rates coming to the fore.

Lack of time and a dearth of sporting facilities are often cited as scapegoats. But the lack of a social infrastructure for the organization of sport is the real foe.

That is why China can learn from the US and European models of sports promotion. I have lived in the US, Britain and Singapore for substantial periods of time. The way sport is integrated into ordinary people's lives is at odds with China's obsession with competition.

It is also this difference that invoked passionate debates within China during the London Olympics. Was it worth sacrificing the wider Chinese public's access to sport for the outstanding performances of the national team? Was it fair for teams financed and trained by a State machine to compete against those made up of entirely voluntary and often self-supported sportsmen and women?

The commercially successful English Premier League or the NBA in the US, both closely followed by Chinese fans, often lead people to overlook the real substance of sporting life in these countries.

The sporting philosophy of these countries - shared educational institutions, sports clubs and sports associations - has the broad, fundamental goal of public participation.

To promote public participation in sport, China should begin by disbanding the professional sports-school system operated by the central sports bureau and use the funds to upgrade sports facilities in schools and universities.

As the Guardian article referred to above notes, it is not uncommon for an average US high school to possess a $1.5 million synthetic-turf American football field, with a six-lane running track and stands for 2,500 spectators, along with a hockey pitch, a baseball diamond and several other fields often irrigated by sprinkler systems.

Widening public participation in sport in China will require an attitudinal shift at the very top of the government and concerted investment in education. Success at past Olympics has served China well but it is time to discard this rather obsession with medals.

The author is senior fellow and deputy director at the China Policy Institute at the University of Nottingham. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily 09/20/2012 page11)

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|