Mining literary material

Updated: 2012-09-20 13:36

By Yang Guang (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

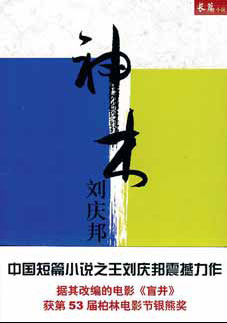

Author Liu Qingbang reveals the hardships faced by miners in many of his works, such as his prize-winning novella Sacred Wood (right). Photos Provided to China Daily |

Former miner and 'king of short stories', Liu Qingbang artfully describes the rural-urban divide in contemporary China

If you introduce yourself as a friend of Liu Qingbang in mining areas across China, people will treat you to a glass of white liquor. Author Wang Anyi learned as much during a trip to a coal mine in Shanxi province.

Miner-turned-writer Liu comments this is the highest mark of respect he has received since he started writing almost 40 years ago.

The 61-year-old is hailed as the "king of short stories" and fellow writers view his works as "textbooks".

Most of his works adopt miners as the protagonists.

"The most frequent motifs of literature, such as the relationships between men and nature, men and death, and men and women, are brought into full play in the dark and grave underground," he says.

For instance, the struggle of human nature is fully demonstrated in his Lao She Literature Prize-winning novella Sacred Wood, whose film adaptation Blind Shaft won the Silver Bear at the 2003 Berlin Film Festival.

Criminals and drifters Song Jinming and Tang Zhaoyang live on the compensation money they extort from scams, such as befriending a naive man looking for a job and telling him that they know of a job at a coal mine.

Once they go down the shaft, they murder the victim and pretend it is a case of accidental death, and then collect payoff money from the mine owners. But the situation gets out of control when a new victim, 16-year-old Yuan Fengming, turns up.

Liu grew up in a rural village in Shenqiu, Henan province. Life was hard on the barren plain. He had little chance to read during his childhood and adolescence apart from fragments of picture-story books.

During the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), he joined millions of red guards in the "link up" movement from late 1966 to early 1967, when students cut classes and traveled across the country to propagate former chairman Mao Zedong's beliefs.

Having witnessed the flourishing city, Liu decided he had enough of the countryside. His effort to join the army failed, however, since his father had been condemned as a counter-revolutionary.

After graduating from junior high school, he had to return and labor in the fields. When the local coal mine was recruiting in 1970, he seized the opportunity and became a miner.

It was then that he began to write, mainly news reports about miners' lives for the county broadcasting station. After working underground for a year, he was selected to join the publicity department of the mining bureau because of his talent for writing.

"Working in the coal mine gave me an opportunity to see a purgatory-like world," he remembers. "Facing my fellow miners, I realized my insignificance and impotence. All the hardships I had endured became nothing."

Liu moved to Beijing in 1978, working as a reporter and editor with a newspaper in the coal industry. In 2001, he became a professional writer with the Beijing Writers' Association.

Some say the way to understand China is to understand Chinese farmers, while for Liu, the way to understand Chinese farmers is to understand Chinese miners.

He explains that most miners are farmers who choose to leave their fields and make more money; while most mining areas are located in an urban-rural fringe zone, where life is a hybrid of urban and rural traditions.

Liu still visits mining areas for part of the year. "The humid air underground and the rumbling of the machines awakens my memory," he says.

Having lived in the capital for more than 30 years, Liu says the countryside he once wanted to escape from now tugs at his heartstrings.

"I was fed with the grains, wild herbs and even bark growing on that plain. Everything there has turned into the blood flowing in my vessels. I will remember that land as long as I feel my pulse."

Since 2011, he has been working on a series of short stories about nannies in Beijing.

Liu says he had been thinking of how to portray contemporary Chinese urban life and picked on the nanny group because they are a large group and are sensitive to human nature.

"The urban-rural divide still exists," he says. "The clash between rural nannies and their urban employers reflects the common conflicts of China's transitional period."

Liu plans to go to a coal mine in Shaanxi province later this year to prepare for his next novel, about the lives of family members of miners who died in a gas explosion eight years ago.

yangguang@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 09/20/2012 page30)