Dangers of a modern playground

Updated: 2012-09-14 09:46

By Haiming Hang (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

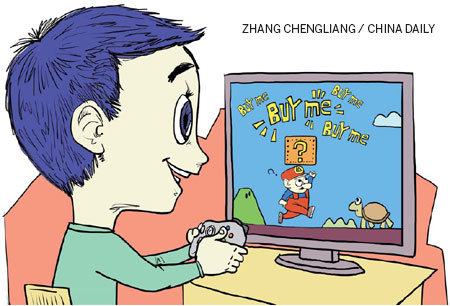

Advertising in video games needs to be regulated, particularly when it is aimed at children

The rapid diffusion of new media such as computers and the Internet has changed the media landscape children face today, as they now spend more time playing online and video games than watching TV. Consequently, advertisers have shifted their investments from mass media to game advertising. It is estimated that by the end of 2012 the advertising industry will spend more than $2 billion (1.58 billion euros) promoting online games, but little is known about how Chinese children understand and cope with game advertising.

Game advertising usually takes two different formats: advergames and in-game advertising. While an advergame is a game specially designed to promote a brand or a product, in-game advertising is the purposeful incorporation of branded messages into an existing game. The key difference between these two formats is that an advergame only features one company's brand, while in-game advertising promotes several companies' brands at the same time.

In both formats brands can appear in different ways. For example, in the Amazing Crispy advergame, players need to collect as many M&M chocolate candies as possible to earn points and proceed to the next level. This is the same for Sneak King, an advergame from Burger King, in which players need to control its brand mascot to deliver food to hungry people before they lose their appetite. In both these games brands are used as key game components and appear prominently. Brands can also be displayed in the background such as on the billboards in racing or soccer games.

The key advantages of game advertising lie in the interactive nature of the media. Unlike television shows or films where the audiences just passively watch the programs, game players can actively interact with the game by manipulating the progress of events, which in turn can enhance their involvement with the brands embedded in games. In addition, games can create a variety of brand-exposure experiences, as players may have a different game experience every time they play. Thus, games usually have a longer shelf life than a 30-second television or film commercial, and can significantly increase players' exposure to the advertising messages.

However, the most important and controversial feature of game advertising is that it blurs the line between advertising and entertainment. People play games for entertainment and fun. Thus, various advertising messages embedded in games may disguise their persuasive intent in a form of branded entertainment.

For example, in the Froot Loops Toss advergame children are asked to either throw Froot Loops (a cereal containing a high portion of processed sugar) or fresh fruits into a monster's mouth to earn points. Children get 10 points if they successfully throw Froot Loops into the monster's mouth and the monster makes an "mmmmm" sound to express its satisfaction. However, children only get five points if they successfully throw fresh fruits into the monster's mouth, following which the monster makes a shorter sound of satisfaction. In other words, this advergame tries to persuade children to develop a preference for Froot Loops over fresh fruit through the entertainment value of a game. But children's limited cognitive abilities cause the majority of them to fail to identify the persuasive intent embedded in the game. For them, the appearance of Froot Loops in the game is just for fun or for information.

Although children may not understand the commercial nature of game advertising, their behavior is clearly influenced by it. For example, playing advergames that promote unhealthy food can make children consume fewer fruits and vegetables but more nutrient-poor snacks. Using a cartoon character (for example, Dora from Dora the Explorer) significantly increases children's requests for the featured brand.

In the case of Chinese children, playing a branded soccer game where the Nike brand logo is displayed on the billboard can make them more likely to choose the brand later. This effect is evident even when the modality of Nike has changed between exposure and test. This is worrying because most game advertising is used by food marketers to promote low-nutrient food that contains high levels of fat, sodium and/or sugars. This may lead to high levels of childhood obesity, damage children's self-esteem and even engender family conflict.

Another controversy of game advertising, in particular in-game advertising, is its unobtrusive nature. As discussed above, advertising in games usually disguises its commercial intent by presenting the brands as part of the game content (either as props in the background or as key game components) and its persuasive message is secondary to the main messages. Since games provide a highly arousing and immersive environment, playing games will occupy most children's cognitive resources and leave little capacity to elaborate on the game advertising.

This, therefore, implies that game advertising may completely bypass children's cognitive defenses and make them unable to resist its persuasive intent. Indeed, research suggests the impact of game advertising on Chinese children can be implicit, with the majority of them failing to remember the advertising but having their judgments influenced by it. Thus, it seems game advertising threatens Chinese children's well-being by jeopardizing their ability to make an informed choice.

Because of these controversies, some have argued that game advertising is covert marketing and is deceptive, as consumers (and children in particular) may not consider it as a marketing effort and will therefore be less skeptical of the information presented. Organizations and consumers holding this view urge public policymakers to intervene to protect consumers' interests.

Others argue that game advertising is not covert marketing, and that it enhances the programs' verisimilitude and subsidises high production costs. They assert that consumers are more likely to be offended if generic products rather than branded products are used in games.

This impassioned debate is part of the reason why game advertising is totally unregulated. In the case of China, advertising laws and regulations need to provide a clear definition of deceptive advertising. By doing that, law makers can decide whether game advertising is deceptive and whether there is a need to regulate it. Furthermore, Article VIII of the Advertisement Law published in 1994 is the only regulation guiding advertising aimed at children in China. It forbids any advertising that may harm the health of children, but it does not provide any standards for determining harm. Such vague legal provisions lead to the problem of subjective and inconsistent adjudication.

Thus, Chinese public policymakers need to consider whether regulations are based on the actual harm or potential harm to children. By doing this, the Chinese legal system can set up clearly articulated advertising regulations to guide advertising aimed at children. In addition, these public policymakers may consider developing nationwide media-literacy programs to educate children about game advertising.

In Britain, for example, some steps have been taken to increase children's understanding of this advertising technique. The British Food Commission set up a website called Chew on This to provide detailed information for children on the use of celebrity endorsements, product placements and advertising online. Although the effectiveness of such programs remains unclear, they can at least enhance children's understanding of the commercial nature of game advertising.

The author is a senior lecturer in marketing at the School of Management, University of Bath. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily 09/14/2012 page11)

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|