Shifting and shaping of financial centers

Updated: 2012-06-08 10:41

By Paola Subacchi (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

China faces challenge of reconciling market-driven financial sector with policy-driven growth

China is now a significant economic power - the world's second largest economy - but punches below its weight in financial and monetary terms. Its economy is deeply integrated with the rest of the world through trade. But its large financial sector has little connectivity with international financial markets. And its currency, the renminbi, has limited international use.

For example, a close look at China's international investment position as a percentage of global stocks shows that China's foreign direct investment and international portfolio assets and liabilities are a tiny percentage - less than 3 percent - of total global stocks. Compare this with its foreign exchange reserves, which account for about 30 percent of global stocks.

To address this contradiction the Chinese authorities have embarked on a cautious journey to open up China's financial system and integrate it into the international financial system. The Fourth National Financial Work Conference that was held in Beijing in January 2012 identifies eight groups of reforms over the next five years, including measures to strengthen financial regulation and financial infrastructure.

These reforms, albeit gradual and almost unnoticed by non-specialists in financial affairs, are critical for China's ability to create a financial sector that is congruous with the size, and relevance, of the country's economy, and to shift its economic growth model toward domestic demand.

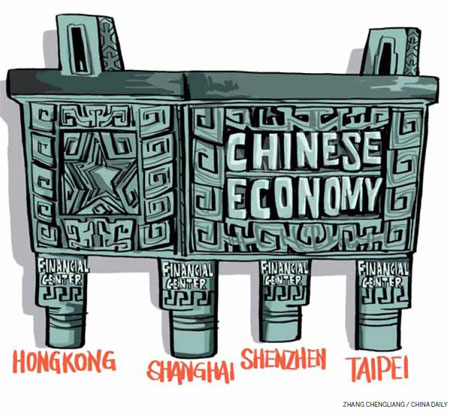

China's financial reform is broad in scale and scope. Hence it encompasses the mainland's financial centers, in particular Shanghai and Shenzhen, and reaches out to the financial periphery with the two leading centers of Hong Kong and Taipei. These are centers that, in different ways and with different competitive advantages, both rival and complement one another in serving China's large economy, as well as helping it become more integrated in the world economy.

These four centers have historically tight links and are also geographically and culturally close. Shanghai and Shenzhen, the two major financial centers on the mainland, have been shaped by the economic reform process since its very beginning. Hong Kong, one of the world's leading international financial centers, is the main player in China's financial opening-up thanks to the "one-country, two- systems" arrangement. Taipei is the most relevant example of the way in which the mainland's financial expansion broadly affects financial centers in the country.

The steps that Beijing is taking, especially the process of internationalizing the renminbi and eventually making it fully convertible, binds these financial centers together and shapes their future development. In particular, Shanghai as the renminbi onshore center aiming to expand its international influence, and Hong Kong as the renminbi offshore center aiming to keep its competitive position are the two cities most affected by China's renminbi strategy.

For instance, in the few years since its launch in 2009, Beijing's renminbi strategy has helped redefine Hong Kong's financial sector. The renminbi is now the third most used currency in the Hong Kong market and accounts for about 10 percent of total banking deposits. Similarly the renminbi lending business and the market for renminbi-denominated bonds have experienced rapid growth. The latter has seen the volume of new issuances in 2011 tripling those issued in 2010. These, together with the rising significance of renminbi IPOs and the introduction of the renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors scheme, are fuelling the growth of the renminbi offshore market.

The reform process in the Chinese mainland will result in a shift to a system more focused on capital markets. It will provide significant potential for growth for Shanghai and Shenzhen as new business opportunities arise from the development of the bond market and the asset management industry. At the same time the growth of China's middle class and the rising number of SMEs will push the demand for financial services and products, offering new opportunities for the financial services industry.

Along with the development of the four financial centers in China, the three financial systems in the region - those of the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan - are expected to undergo a certain degree of integration over the next 10 years. The development of Hong Kong as a renminbi offshore center has reinforced the financial linkages with the mainland, and this process is set to continue, leading to more systemic integration. Within this framework, closer cooperation among Shanghai, Hong Kong and Shenzhen should develop gradually.

For example, it will be both technically and politically feasible to form a multi-tiered trading platform as well as a broader equity market in the region over the coming years. Meanwhile, a currency repatriation scheme, bridging the renminbi onshore and offshore market, is also shaping up between Shanghai and Hong Kong.

At the moment the degree of cooperation among the four financial centers implies the emergence of a "division of labor". But it is hard to see this as a sustainable arrangement, particularly once China's capital account is fully liberalized. If and when the policy barriers are relaxed, market forces will ultimately lead capital resources, business and talent to cities where the market is most efficient, cost-effective and profitable, and where it is most pleasant to live. By that time, only those financial centers with a strong competitive edge that cannot be eroded by policy decisions from Beijing will find themselves at the top of the league table of international financial centers.

Hong Kong is likely to remain the dominant international financial center in the region because of its well-developed regulatory system, its existing reputation as the most liberalized financial center in Asia and its unique competitive advantage over other centers such as New York or London - the "China dimension". Despite concerns that the mainland authorities may expect it to make way for Shanghai eventually to become the largest renminbi onshore market by 2020, Hong Kong is likely to maintain its competitive edge for a long time to come, irrespective of policy shifts or decisions made in Beijing. Even if Shanghai manages to close the gap with Hong Kong, the size of the mainland's real economy indicates that the country has ample capacity to accommodate two major international financial centers in the longer term.

For its part, Shenzhen will mainly serve as a domestic financial center, focused on the needs of SMEs and start-ups located in Guangdong. Taipei, on the other hand, can benefit from its experience with high-tech SMEs in the broader Asia region to target mainland SMEs at a relatively advanced stage of growth. Although the capital markets in Taiwan remain small relative to other centers in the region at present, further cross-Straits cooperation in the financial sector, along with the mainland's financial reform process, will provide Taipei with new opportunities as a complementary regional financial center.

China's financial reform is a complex policy-driven process with several overlapping levels and related goals - from the reform of the banking system and the development of the bond market to the interest rate and exchange rate reforms. Most of all, it is where political considerations and market preferences meet. Thus China faces the difficult challenge of reconciling the need for an efficient and market-driven financial sector with its policy-driven growth strategy.

If all goes according to plan, China will eventually emerge on the international scene as a major financial power, the issuer of one of the key reserve currencies within a multi-currency international monetary system, with deeply connected international financial centers where domestic firms work alongside international ones. China's financial transformation will eventually correct the fundamental problem that afflicts the international economic and monetary system - where the world's second-largest economy and the top exporter is managing its exchange rate, resulting in a large current account surplus and a very large accumulation of foreign reserves.

What China is doing is critically important not only for the development of the country, but for the world as well. It is also historically unprecedented. Thus there is ample scope for policy experimentation, and the challenges are enormous. Possibly the most difficult of these challenges is that China has no roadmap or experience to rely on.

Most of all, there is no official timetable beyond a few goalposts. China's financial reform is a gradual process, the full impact of which is likely to be noticeable in five to 10 years. This may sound far too slow given the current urgency of rebalancing the world economy, and disappointing in the short term. But it is critical that China carefully manages its transition to a modern financial system. A financial crisis, or protracted financial instability in China, would have a systemically devastating effect on the rest of the world.

The author is research director, international economics, Chatham House, London. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily 06/08/2012 page10)

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|