An end with horror is better than horror with no end

Updated: 2012-06-01 10:53

By Giles Chance (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|||||||||||

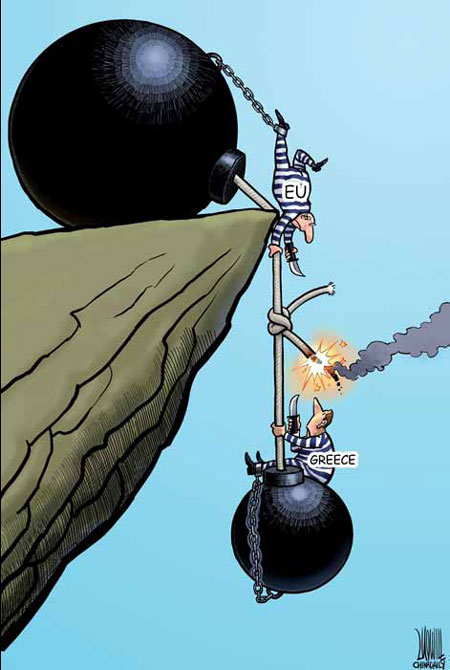

Did you know that the Germans have a sense of humor? It's well-hidden, but you can see that they do from the title to this article, which is a German comment on the European situation. I think it accurately pictures where we've arrived, after several years, much discussion (including many European summits) and an enormous amount of commentary. The crisis continues, the situation for ordinary people in Greece, Spain, Portugal, Ireland and Italy is getting worse, and it does not look like improving. The situation can't continue like this, so of course it will end. In this article, I want to look at what that end might be, and what this end will mean for China.

The financial crisis in Europe is not the first major financial crisis to have happened in recent times. In fact, there have been many financial crises since 1980, and they all have the same things in common - excessive debt and uncompetitive economies. We have a lot of data from the recent past on how financial crises happen, and we know the necessary steps for resolving these crises.

What are they? The first step is to forgive some debt, and restructure others, with grace periods, longer payback terms, and lower interest rates.

This leads us to the second step - the clean-out of bad commercial bank debt, changes in bank management, and the recapitalization and restructuring of the banking sector. For growth to start and strengthen, banks need to extend credit.

They can't do this if they are suffocated by a pile of bad debts, because they need all their cash inflows to cover their bad debts and replenish their own capital.

A third step is for wasteful government spending on unnecessary current spending to be cut, because this reduces budget deficits and new debt. At the same time, and fourth, there must be improvements in country economic competitiveness, including exchange rate devaluations and structural reforms like tariff reductions and increases in labor flexibility.

Finally, it's necessary to offset the negative effects of bank deleveraging and budget cuts with investment which gives economic returns and also creates employment, for example into infrastructure - roads, bridges, airports.

Let's check now the steps that Europe has taken to resolve the crisis, against the list above. Debt forgiveness and restructuring? There has been some, particularly in Greece, but there should be much more. A clean-up of bank debts and bank recapitalization? - they've hardly happened. Cuts in budget deficits? Big efforts have been made to reduce wasteful spending in Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Greece, but France hasn't started yet. As economies continue to shrink, these cuts always look like too little, too late, because they need to be accompanied by sensible investment programs which start to reflate the economy. Improvements in economic competitiveness? A start has been made with cuts in wages in several countries, and changes in labor laws in Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece. But much more needs to be done. Economic reflation? There hasn't been any.

Out of a possible maximum of 10 marks for successful crisis management, we award the Europeans 4, calculated as follows: 1 for some debt restructuring, 2 for cuts in spending, and 1 for some attempts to improve economic competitiveness. Although 4 out of 10 is quite generous, it's still obviously an F grade for Europe.

Europe's F grade for resolving, or not resolving, the financial crisis means that things are going to go on, and they're going to get worse. So how does the horror end? It can only end one way: by the splitting-up of the euro into two groups. One group includes countries which are able to live with Germany's economic efficiency: Finland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium and France (probably); Italy (maybe), plus the smaller, newer members such as Estonia, Slovenia, Malta and Slovakia which haven't had time to develop bad spending habits and large debt loads.

The second group consists of the euro members whose economies are highly uncompetitive with the "strong" economies led by Germany. This group includes the following countries: Greece, Cyprus, Spain, Portugal and Ireland (and may Italy too). All of these weaker countries will have to leave the euro system, perhaps to rejoin at a later date once they have reformed their economies to improve their competitiveness. But after they leave the euro, they will have to return to using national currencies. These will immediately devalue by between 30 percent and 50 percent against the euro, thereby pricing their domestic products much more competitively against foreign competition.

After an initial shock of a few months, the country will start to regain much of the competitiveness it needs. Growth will restart, employment opportunities will grow, and government tax revenues will start to rise.

When will this happen? If Germany does not agree to back all euro banking deposits, then Greece could leave the euro very soon as the trickle of Greek bank deposits into German banks becomes a flood. Even if the Greeks decide in the next mid-June election to create a government which follows the agreed program of spending cuts and economic reforms, those difficult steps then have to be carried out under the hard gaze of the European Union and the International Monetary Fund.

I don't think the Greek people will do it, nor do I think that the Germans will guarantee Greek deposits or allow new money to be paid to Greece without a significant sign of Greek budget and reform compliance. So I expect Greece to leave the euro before the end of August, probably earlier. The pressure will then turn onto the others - Portugal, Spain, Ireland - which, as they come under increasing pressure from the market, will ask for more financial assistance while they reform their economies. Pressure from rising unemployment and continued recession will probably force these other, weaker countries to leave by the middle of 2013. By 2014, I expect that the likely result will be a new kind of euro with economically strong and disciplined countries such as Germany, the Netherlands and Finland at its center, and also including Belgium, France and Italy, all of which have work to do in terms of economic reform, but whose omission, as founder-members of the European system, cannot be considered.

Once the crisis starts to moderate, the euro will become a stronger currency than it has been in the past, although the euro area will have shrunk.

For China, the economic impact of the solution to the euro crisis that I have described will be bad in the short term, but in the medium and longer term may provide many opportunities for direct investment and the capture of valuable technology and brand names.

China has already started to suffer the impact of the euro crisis because Europe, its largest export market, is hardly growing. This negative euro impact on Chinese exports and growth will continue through 2012 and into 2013. On the other hand, European investment into China, which is made largely not by governments, but by large multinationals, will probably not be much affected, because Asia is the first destination for European companies which need to find new markets outside Europe.

Certain European countries, particularly France, Italy and Spain, have resisted large foreign investments into industries that they consider strategic, like banking or telecoms. But if I'm right, and several southern European countries are forced out of the euro, then European investment opportunities will become more available and much cheaper for outsiders with capital to invest, such as China. Even countries which do not leave the euro like France, will be inclined to relax some of their controls on Chinese inward investment into "strategic" industries.

In the absence of a well-executed five-point plan of recovery from the crisis, the euro countries will be forced to a market-determined solution, which will separate the weak euro economies from the strong ones. The time for a well-executed recovery plan in Europe is nearly over, and an end, with horror, is nearly upon us. But that's a lot better than horror with no end.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|