Gen Next

Updated: 2012-05-25 08:25

By Zhao Yanrong (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|||||||||||

Liu Yikong is a vexed manager these days as only a few job seekers are turning up at the recruitment center of Huajian Shoes Co Ltd in Dongguan, Guangdong province - just enough to keep his production lines humming.

Elsewhere in the other major manufacturing hubs of China, the situation is no different, as labor shortages are fast emerging as the top concern for most companies.

|

||||

Leaving aside the broader macroeconomic factors - the inevitable rise of labor costs which has already caused some low-end manufacturing to move to lower-wage countries, increased automation at some plants and squeezed margins for the thousands of plants which do original equipment manufacturing for foreign multinationals - it is obvious that winds of change are fast sweeping across the labor landscape and a new breed of migrant worker is demanding the rewards of a strong and vibrant economy.

According to a recent survey conducted by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the average wages of migrant workers went up by 21.2 percent in 2011 to 2,049 yuan (255 euros, $323) compared with 2010.

But looking at the broader picture, it is obvious that there is much more than meets the eye. Companies have realized that dangling the wage carrot is not enough to ensure a steady supply of labor. Rather, they are finding that it also means throwing in a host of facilities and incentives to create a better working environment to retain them.

Though a labor shortage is still an enigma to many in China, some experts point out that the current pool of migrant workers is indeed the crux of the country's future workforce.

Changing workforce

The proportion of migrant workers in China aged between 16 to 30 has fallen from more than 60 percent of the total in 2009 to less than 40 percent last year. At the same time, the total number of Chinese migrant workers rose to 252.78 million in 2011, up 4.4 percent from the 2010 numbers, says a report released by the National Bureau of Statistics in late April.

What this also means is that though the numbers have gone up, the available pool is fast shrinking, a major concern considering that they hold the key to China's industrial fortunes.

It also comes as no surprise that the new generation of Chinese workers are poles apart from their older peers when it comes to desires and needs.

For starters, the younger generation of workers possess better levels of education than their older peers and hence have higher expectations. They are also clear on their material needs and are also less tolerant of rigid working environments.

"The new generation of migrant workers are an important force in China's economic and social development. Their working skills and attitudes directly have an effect on the competitiveness of Chinese products in the world," Han Changfu, the minister of agriculture, said in February.

From a corporate perspective, significant changes in management practices have been made to retain the young labor pool.

"Running a company does not mean that you are the boss but more of a nanny now. Companies that cannot take care of their workers will find it hard to retain and attract labor," says Liu Kun, the spokesman for Foxconn Technology Group, one of the largest electronics contract manufacturers in the world making products for Apple and HP, among others.

The idea of a new generation of migrant workers was officially mentioned for the first time in a document released by the State Council in January 2010, which called for resolution of the problems faced by the young group of workers to better enhance their urban integration.

The document particularly refers to people born in the 1980s and 1990s in the rural areas of China, especially those who did not undertake much farming activity and rather focused on building a career after school.

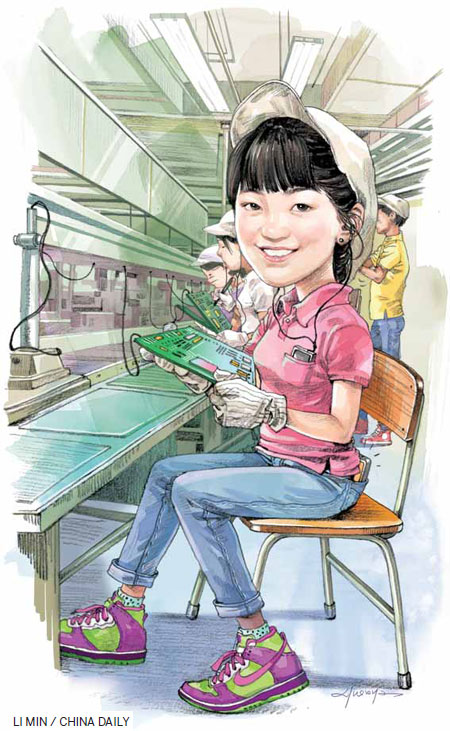

Two examples illustrate this new breed.

In Dongguan, home to more than 8 million migrant workers, 22-year-old Li Chunta waited for half an hour in the lobby of a recruitment center, but could not find a single job that was to her liking.

"I want a job which does not require me to work on night shifts, or on assembly lines with a lot of dust and noise. I also want to find a job that is not too boring," says Li, who graduated from a technical secondary school.

Li hopes to find an office job or employment as a warehouse keeper in Dongguan for a monthly salary of about 2,500 yuan. This, she says, was the same amount she earned during her six-month stint at an electronics assembly line in neighboring Shenzhen.

"Working on the night shift is very taxing. My previous job was extremely boring, as I had to repeat the same moves hundreds of times every day without too much thinking. My team leader was also too serious a person to work with," she says.

Li has the freedom to pursue her ambition, as her parents are not dependent on her income. Since her elder brother takes care of them, there is no real financial pressure that is forcing her to find a job immediately.

"I have been in Dongguan for just a week. Since I have some working experience, I want to find a job that I can enjoy," she says.

Though she is the daughter of a farmer, Li cannot be found wanting when it comes to trends and fashion. She has dyed her curled hair in a light brown shade and was dressed in a trendy designer chiffon shirt with a small leather handbag in tow.

Like many of her generation, Li comes from a rural area but is urban in outlook. Her peers prefer jobs that are less demanding, like office work, and an urban lifestyle is a bigger draw than higher wages.

Zhou Shujun, recruitment manager at Chtone, a leading Chinese employment agency, says that the labor shortage in China has been compounded by a growing number of candidates like Li.

"The total number of job seekers is more or less at the same level. But there are fewer young people than before who want to work on the production lines. They also change their jobs frequently, thereby creating a labor shortage throughout the year," says Zhou, who is responsible for mostly hiring assembly line workers.

The situation is so bad, Zhou says, that some young workers have changed as many as six jobs in just two years. "In some cases, people quit just because they did not like the taste of the food in the workplace canteens.

"Many young migrant workers are not clear on how to advance their careers, especially in the first two years after school. Most of them are keen to live in cities and view a factory job as a stepping stone to urban life," Zhou says.

|

|

For 21-year-old Yang Luoke, born in a village in Wenzhou, Zhejiang province, employment is all about leading to his own business.

Displaying the indomitable business streak that typifies people from his hometown, Yang has ambitions of striking it out on his own at some point.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|