Thread by thread, safety net gets stronger

Updated: 2012-05-11 11:36

By Giles Chance (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

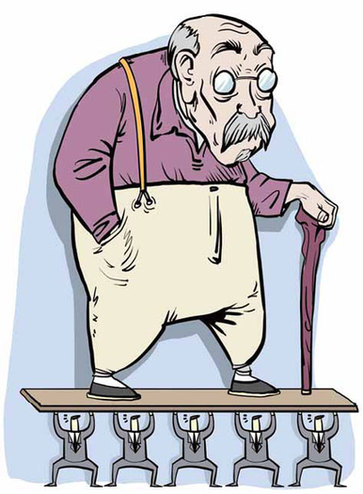

Good investment returns of social security funds key to providing for retired workers

Zhang Chengliang / China Daily

What will China look like in 2030? If you're Chinese, at first sight the future looks bright. By then, China will likely be the largest economy in the world, overtaking the United States in size probably between 2020 and 2025. China will be much more integrated with the rest of the world than it is today. The Chinese renminbi will be a major global currency, and China will be playing a dominant role in the world's major institutions: the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Driven by productivity gains, after-inflation wages will have risen substantially.

Two-thirds of the Chinese people will be urban dwellers and will be much richer than they are today. The majority will be middle-class - meaning they own a car (or two), as well as the house or apartment they live in. As the under-developed parts of China catch up with the developed parts, inequality between the west and east of the country will have fallen. The Chinese middle class, which today has already started to play a role both in Chinese and world affairs, will have become a dominant force within China and highly significant globally. And the Chinese environment will be cleaner.

But there's another side to the picture. As China's economic gains come to depend less on dramatic economic modernization and more on incremental productivity gains, over the next 30 years China's annual economic growth rate will fall, from the current 8-9 percent to somewhere around 4 percent. This will make the economy easier to manage, but will also leave less room for mistakes. An economy growing at 9 percent every year doubles in size in eight years; at an average growth rate of 4 percent, the doubling in size takes about a decade longer.

And China will age rapidly. The 2010 China census showed that 13.3 percent of the 1.34 billion Chinese were aged over 60 - a rise of 3 percentage points since 2000 - while the proportion of under-14s had fallen by over 6 percentage points since 2000, to 16.6 percent of the population. United Nations projections show that in 2030, nearly 25 percent of Chinese will be over 60, and by 2040, the over-60 group will have risen to nearly one-third of the population - higher than in the US, where in the same year, the over-60 group will not exceed a quarter of the population thanks to America's ethnic and cultural composition.

At the same time, China's labor force, whose steady growth in the 1980s and 1990s added about 2 percentage points to economic growth each year, will start shrinking soon. After 2015, the Chinese combination of fewer workers and more retired people means that the number of working people available to support each retired person (the dependency ratio) will fall. In 2000 the dependency ratio was 6.4 workers to each retired person. Today the ratio is 5.3. In 2020 it will be just over 3, and by 2030 it will be 2.5.

It will become steadily more difficult for working people to enjoy higher living standards, while paying more to the government in tax (or social insurance premiums - effectively the same thing) to support the increasing number of old people. That steady and substantial fall in the dependency ratio means that, unless something changes, a lot of working Chinese people now aged between 25 and 40 are going to experience a sharp drop in their living standards when they retire, because the money to support them for 15 or 20 years after their retirement at 60 (and for longer if they are female) isn't there.

Historically, China has lagged behind other higher middle-income countries in providing social welfare, like pensions and healthcare. China's unique recent history explains why. From the founding of New China in 1949 to the early 1990s, State enterprises were responsible for every aspect of their workers' welfare - starting with their birth and early education, and ending with their funeral and burial. The dismantling of the State enterprise system in the 1990s left more than 50 million Chinese people without a job or social welfare support. The responsibility for supporting these people now fell on their families - if they had them - and produced a large increase in the number of unemployed and retired people.

Understandably, given its social convulsions in the last half-century, it has taken some years for China to develop social security systems which can provide adequate support to retired people as well as to the unemployed. Early efforts made in the 1990s and in the early millennium were only partly successful for a number of reasons: narrow and patchy coverage, particularly in rural areas; low contributions; low or negative rates of return on invested contributions, and the use of investments by local governments for purposes other than social welfare.

Similarly, although Chinese doctors and nurses are often highly trained and dedicated, the Chinese healthcare system, largely funded from the sale of hospital drugs, could not provide medical care reliably and efficiently to most Chinese.

However, China started to include pension coverage and healthcare targets in its 11th Five-Year Plan (2006-2010), and focused a part of its post-crisis economic stimulus in 2008 and 2009 on building hospitals and developing healthcare in smaller Chinese cities and towns. Between 2005 and 2010 pension participation among Chinese migrant workers doubled, to 40 percent.

In late 2008 the government introduced a voluntary rural pension scheme, which has seen 100 million new contributors. This scheme, which was replicated in urban areas in 2011, is intended to become universal and compulsory by 2020. The Social Insurance Law, which became effective in China on July 1, 2011 and applies equally to foreigners working in China, was aimed at providing universal coverage for old age, illness, work-related injuries, unemployment and childbirth.

The system combines the two different approaches adopted in other advanced countries, of full funding in advance, and pay-as-you-go. It is based on a system of contributions by employers and employees which are invested. These are backed by government support to ensure that benefits can be paid if invested contributions are insufficient.

China's aggressive moves in recent years to upgrade its social security systems are partly a response to critics who have argued that China's extremely high savings rate and relatively low level of household spending, which unbalances the economy, are the result of the insecurity which derives from inadequate social welfare support. But we won't know for some years whether this theoretical link between high savings and inadequate social welfare is actually borne out in practice - or whether it's just the imagining of foreign economists, as was suggested by an article published in 2009 on the website of the People's Bank of China.

Several factors will determine whether China's social security systems will be successful in supporting China's rapidly aging population. As Chinese people become richer, their health will improve, and they will live longer. China's average life expectancy across men and women was 71.5 years in 2005, and is projected by the United Nations to rise by 2040 to over 77. Steadily rising life expectancy can be balanced by raising retirement ages, but this is always an unpopular and difficult step for governments to take.

We also know that, over time, fewer workers will be available in China to support each retired person. But Chinese real wages will tend to rise, and workers should be able to increase their contributions to social insurance schemes.

However, the most important variable determining the success of social insurance schemes is the annual return obtained on the pools of invested social welfare contributions. Up till now, most of these contributions have been placed in accounts operated by local governments, and invested in Chinese savings deposits, at low rates of interest. Investment returns, combined with low contribution rates, just haven't been able to keep pace with retirement demands. The central government has often had to step in to subsidize local government pension schemes whose assets have exhausted prematurely.

In 2000 the government established the National Social Security Fund with the purpose of supporting provinces with their financing of pensions. After the NSSF began in 2003 to diversify its investments overseas and across different kinds of assets, its investment returns improved dramatically, averaging 9.2 percent each year between 2001 and 2010, against an average annual Chinese price inflation rate of 2.1 percent. In March this year, the provincial government of Guangdong announced that it would hand 100 billion yuan ($15.9 billion; 12.2 billion euros) to the NSSF to manage on its behalf - starting a trend that other local governments may follow, as they themselves lack the investment experience to be able to realize solid returns every year, without taking large risks.

Good long-term investment success will reduce the demands that the government will have to place on Chinese companies and workers.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|