Dark prejudices that throw a dim light

Updated: 2012-04-06 11:03

By Cui Hongjian (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

| Zhang Chengliang / China Daily |

The perception of China by Europeans has gone through different periods of change. Twelve years ago the European media displayed goodwill toward China. Whatever the motives behind it, whether they were political or economic, the mainstream view was that China was on the road to change.

But political change that was in sync with European experience and logic failed to occur. Goodwill toward China thus began to ebb. It was replaced by disappointment and concern aired by European media and the public alike, and this sentiment was reflected in a shift in European Union policy, from one of unconditional access for China to one of conditional engagement.

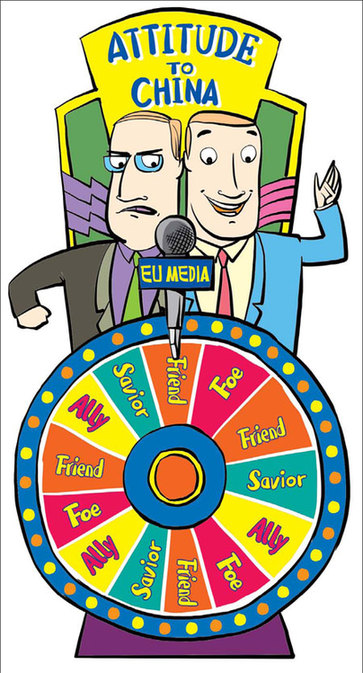

European media began to see China as an authoritarian state with rapid economic growth, and the ideological bias gradually became prevalent in public opinion toward China. The media began to focus on China's human rights and other political issues, and they also began to become wary about China's economic policies and moves on energy resources that they reckoned posed a challenge to Europe.

Correspondingly, public opinion polls show that since 2006 the positive image of China in most European countries has fallen, while negative perceptions of the country have risen.

That China was on the nose was most obvious in 2008. The issues of Sudan, the Beijing Olympics torch relay and the Dalai Lama were topics of hot debate among Europeans. Chinese and European media and public opinion had increasing differences and even opposing stands in their reporting positions and perspectives. Indeed, at one point a European scholar reckoned that over the previous five years, when it came to China, Europeans were treated to reports on the country's economic opportunities, but in the previous six months they were told constantly about China posing a threat in Darfur and Tibet.

China and Europe would later be at loggerheads. Following the Copenhagen climate change conference at the end of 2009, the Iranian nuclear issue, and the Sino-Japanese dispute, European public opinion shifted to regard China's stance as too tough, a sentiment that turned into disapproval of China.

However, because of Europeans' increased focus on China, more people are seeing the country from many different perspectives. Events such as the Sichuan earthquake of 2008, and reporting on how China reacted to it, and the fact that the country has served as a stabilizer in world economics have prompted Europeans to look at China's "multi-faceted and complex character". European media reports on China in recent years have become more comprehensive, no longer confined to traditional issues such as politics, economics and security.

News and opinion on China is becoming ever more ubiquitous, on radio on television and on the Internet, and views on the country are becoming more rational.

If you look at the way media and public opinion and policy interact, it becomes clear that bias in the media and among the public will create differences between China and Europe, which is not good for anyone. In Europe's political environment, public opinion has been drafted into the role of "spokesperson for the public", thanks to the help of the media, and this has had a great impact on European foreign policy.

For example, the European media's enthusiastic take-up of the so-called Tibet issue resulted directly in hostility between China and France, and in mutual mistrust and resentment, which in turn put the two governments under domestic public pressure.

European media respects the independence of public opinion and the fundamental principle of freedom of the press. From what I can understand, the principle emphasizes on the one hand that public opinion should not be subject to the politics, the will of interest groups and the impact of the changing situation in the political environment. On the other hand, as the representatives of a civil society, the principle enables the media to have the undoubted rights to free expression of all kinds of opinion.

When this principle is reflected in reports and opinion on China, the media sometimes have to sing a tune that does not reflect their government's policy on China, and to give air to a variety of voices, sometimes with views that are controversial or even extreme. The result can be people grandstanding, airing cynical views or ignoring the truth and any reasonable representation of facts.

When it comes to reporting on other countries, the media and the public, recognizing cultural and historical differences between countries, need to be objective and fair rather than just sticking to the freedom-to-say-anything principle.

Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation has had a spate of scandals in Britain recently that illustrates how difficult it is to dissociate the media and public opinion from interest groups. It may be that "freedom" is an unattainable goal.

When the European media mold the image of China, another problem they cannot avoid is the perspective of a Euro-centric view. The so-called centered view refers to making Europe's own historical experience, cultural traditions and ideology a universal standard, serving as the gauge when it comes to Chinese affairs.

Looking at China using this approach, they are bound to come up with an image of China strung together using a sorry assortment of labels: the inscrutable country of the East, the one with the heterogeneous cultural genes, the godless society, and the Communist country that is not democratic. The risk is that in the absence of a more realistic picture, this image will be reinforced by European media that have their own blind spots and political agendas.

The European debt crisis may provide opportunities to enhance mutual understanding between China and Europe. After all, the two sides have never in history closely related to each other in this way. After the Chinese media paid close attention and had lively discussions over the crisis, they came to the conclusion that helping Europe was a matter of self-interest.

When political leaders of China and the EU agreed that they pull together to survive the crisis, and came up with the ambitious goal of building China-EU relations as a positive model for 21st century international cooperation, the European public was clearly not ready. It continues to display complex and sometimes conflicting states of mind toward China.

On the one hand, in the face of globalization, there is a tendency in Europe to conclude that what China has gained is what Europe has lost. Many people buy this idea. They also tend to project the idea of rivalry in economics and business onto the spheres of development models and values.

On the other hand, Europe hopes to develop relations with China, and derive tangible benefits from it, winning time for it to ease the crisis and push forward reforms. European politicians have to constantly make shifts to stay in step with public opinion, which, can sometimes cause waves.

If Europeans are still reluctant to prepare for changes, and want to insert negative influence on Europe's China policy, they will not only tarnish China's image, but also miss out on outside support to resolve their crisis.

The author is director of European Studies at the China Institute of International Studies. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|