Long-term view pays off in long run

Updated: 2012-03-16 07:32

By CHEN WEIHUA (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

US must anticipate, rather than resist China's growth

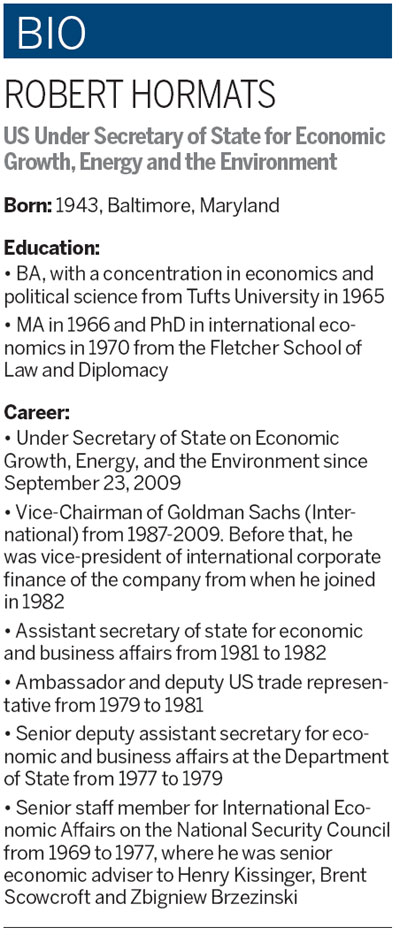

Robert Hormats was a young economic adviser to Henry Kissinger at the National Security Council in 1971 when the latter made two secret trips to China before Richard Nixon's historic visit in 1972.

At that time, the two nations came together on geopolitical concerns, mainly the Soviet Union and the war in Vietnam.

"Hard as it may be to believe today, the opportunity to expand economic ties actually was very low on the list of priorities for either the US or China," says Hormats, now under secretary of state for economic growth, energy and the environment.

That was also reflected in the Shanghai Communique, a bilateral statement announced during Nixon's visit. There were only two sentences on economic issues.

There were also many practical difficulties to opening bilateral trade since many US export control regulations and other restrictions that had begun during the Korea War in the early 1950s and accumulated over decades were still in place.

After Nixon's trip, Hormats and his National Security Council colleagues began to explore further expanding economic ties. He and the late John Holdridge, who went on Kissinger's secret trip, produced a memorandum on recommendations for a working group on trade issues. That modest set of economic issues outlined include the resolution of frozen assets, the question of most favored nation status, travel between the two countries and industrial and intellectual property protection.

In 1973, when Kissinger asked Hormats to get the US private sector, which at that time had virtually no contact with China, more engaged "in order to get more non-governmental support for the relationship", Hormats and the then commerce secretary Fred Dent worked with business people to set up the National Council for United States-China Trade. That organization, renamed US-China Business Council in 1988, has now become a key advocate in the US of the expanding bilateral economic relationship.

|

The dramatic turn of bilateral economic ties came in the late 1970s with the normalization of diplomatic relation and China's launch of the reform and opening-up policy. Bilateral trade in goods increased from $95 million (72 million euros) in 1972, to $7 billion in 1985 and $365 billion in 2010.

The example Hormats likes to give is the deals during Chinese President Hu Jintao's visit to the US in January last year. Boeing signed to sell 200 aircraft to China for an estimated $19 billion while GE Transportation clinched a $1.4 billion contract with China's Ministry of Railways, including export of locomotives, sub-assembly, service support and signaling systems.

"Before 1971-72, US exports of aircraft and locomotives to China were prohibited," says Hormats, who attended almost all of the meetings during Hu's visit and also Vice-President Xi Jinping's visit to the US last month.

While hailing the breathtaking progress in bilateral economic ties, Hormats says the two countries still have many obstacles to overcome. For instance, some countries, including China, often regarded "nationalistic domestic standards and restrictions" as "an attractive model for their economics", he says, something that is to be discouraged.

The 68-year-old agrees with the views in the China 2030 report unveiled in Beijing three weeks ago by Robert Zoellick, the World Bank president and Hormats' former colleague at Goldman Sachs. The report recommends China pursue a new round of reforms in order to sustain its future economic growth.

"What served to enable dramatic improvements over the last 40 years - producing a spectacular rise in the living standards of hundreds of millions of people and in China's overall economic growth - may not be the kinds of policies or practices that will do so over the year 40," Hormats says.

"More than most countries, China should see the long-term benefits of reforms that recognize - as Zhu (Rongji) and Deng (Xiaoping) did - that adapting internally to many of the elements of the market-oriented, rules-based international system can be good for growth and economic vitality in China," says Hormats.

He believes any initiatives to encourage China to conduct the reforms will be most effective when they are framed in a way that clearly relates to China's own interests, such as the highly positive role it has played in the G20 in managing the recent global financial crisis.

"The most astute US approach would be to anticipate, rather than resist, China becoming richer and more powerful, and encourage it to recognize that adhering to global rules and norms is not incompatible with this process but in fact will enhance it and ensure its sustainability," says Hormats, a key figure in the bilateral Strategic and Economic Dialogue.

Unlike 40 years ago when geopolitics and the external environment pushed China and the US together, Hormats sees many of the compelling priorities for the two countries today as internal in nature - jobs, growth, the environment and social equality.

"We must find ways to ensure that US-China relations support these internal objectives in both countries - and that one side does not seek to accomplish them at the other's expense.

"If we work together and avoid seeing our relationship as a zero-sum game, then mutual success is possible. If we do not, then success in each of our economies will be far more difficult."

Some concrete policy recommendations Hormats provides include increasing Chinese investment, ramping up agricultural trade, engaging China in the WTO and other multilateral institutions, insisting China maintain an environment that protects intellectual property rights, collaborating on environment and climate change and bringing together US governors and Chinese provincial and municipal leaders to cooperate on economic, energy and environmental issues.

Hormats is especially concerned about encouraging "competitive neutrality" regarding China's State-owned and State-supported enterprises.

"We don't argue with China's desire to have SOEs, but often massive government support of these entities grossly distorts international and domestic competition. That ultimately harms not only foreign investors and exporters but many Chinese firms as well."

However, he thinks this will not be an area of contention at least in the long run because China will look at these SOEs and decide it is too expensive to support them with large sums of money, which could be used to support social security, healthcare and education.

Hormats believes that a serious China will think about the economy in the long term. "One of the great strengths of China is Chinese are long-term thinkers," he says.

Having traveled more than 60 times to China since the early 1970s both in his government and private se

ctor role, Hormats says he is always optimistic about the economic relationship.

"You have to be if you are going to do these jobs well. If you are intuitively or instinctively pessimistic, you won't get anything done.

"You have to look at this relationship as a great opportunity. I could be frustrated from time to time when things don't go well, or not move as rapidly as I hope, but never pessimistic."

Contact the writer at chenweihua@chinadailyusa.com

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|