Tackling 'difficulties' in bilateral ties

Updated: 2012-03-09 11:33

By Fu Jing (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Beijing, brussels still trying to 'find each other'

|

|

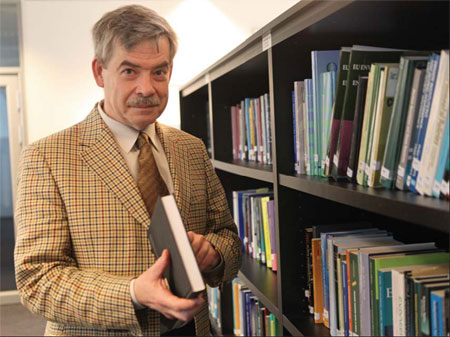

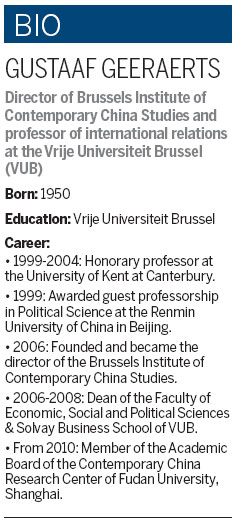

Gustaaf Geeraerts says both China and the EU should do their homework to make a sustainable relationship possible. Fu Jing / China Daily |

Every time Gustaaf Geeraerts hears about Europeans' misconceptions about China, he suggests they book a flight to the country and go and explore its dynamics and complexity.

"Please fly to China and stay there at least for three days," he says. The mission for Geeraerts, founder of what is believed to be the only research institute in Brussels that focuses on China, is to help Europeans understand the rapid changes that are taking place in the world's most populous country.

However, it seems this is still a difficult task for the professor, who believes that China's rapid rise is not a danger but presents a chance for "sleepy" Europe to reinvigorate itself.

"Both China and Europe suffer an identity dilemma," says Geeraerts, director of the Brussels Institute of Contemporary China Studies.

Sitting in his office in downtown Brussels, Geeraerts repeatedly uses the word "difficult" when talking of bilateral relations.

|

"We are going through a very difficult time of very fundamental changes ... and the relationship between Beijing and Brussels is still at a very difficult stage with both sides trying to find each other."

His views contrast with what might be considered the official line.

A delayed China-EU annual summit in Beijing last month ended with a five-page consensus on various topics, and both sides have even agreed to look at China's market economy status, trade protectionism and to come up with a bilateral investment agreement.

For Geeraerts, the results are not that surprising and need to be looked at as a work in progress, mainly because the gradual change in the global order makes it difficult to reach common ground quickly.

"To be quite frank, both Europe and China have just arrived at the point that they realize they need to get their fundamentals right."

Last month's summit and the EU-China relationship ought to be seen in the broader context of the changing global political and economic system, he says.

What the financial crisis since 2008 has highlighted, he believes, is an emerging change in the world order. The dominant Western powers, including a Europe that has lived comfortably in the shadow of the US, are now having to deal with the growing influence of emerging powers.

Among those powers, China is the No 1, and its rise in the past 30 years, especially in the past 10 years, is extraordinary, he says, adding that even though its GDP per capita is relatively low, its economic clout is growing.

He also says it is obvious there is a need to move the relationship beyond a purely economic one, China and the EU having a common interest in international stability.

"Should (the Middle East or Africa) turn unstable, both China and Europe will pay a price," Geeraerts says. "We have to support each other in building solid global government structures.

"But there are a few problems here. Maybe that's too much my view as an international scholar and teacher."

He says it is a problem of identities of actors. Europe has a more post-modern identity while China has a more modern one, keen on its sovereignty, the principles of non-intervention in internal affairs. And it is true the EU is too internally divided to speak at a political level.

"In my view, China's rise leads to a different world constellation. I am not pointing fingers at anyone. These are objective developments," says Geeraerts, adding that Europeans generally feel more comfortable than Americans in facing the facts.

And now the rise of emerging economies including China is putting the structure of global governance under increasing pressure. International organizations such as the World Trade Organization, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund were designed by the US and were largely supported by its Western allies.

Now, Geeraerts says, the US is facing a crisis and Europe is grappling with its sovereign debt problem, and all this comes as China fares much better than anyone else. So Europe needs to adapt to the new environment.

"But the developed economies become, in a way, less legitimate because they do not represent as before the economic power. That's a fundamental evolution, and the financial crisis has put it very much on display."

It used to be that in its dealings with China, the EU acted as though there were strings attached to what it offered.

"Brussels used to think 'we are willing to help you but you know our model, and we would like you to evolve to a kind of image of ourselves. We are convinced that it is a good model. If more widely applied, it will lead to a peaceful world'."

But things have greatly changed, he says. "And this kind of perception and identity no longer holds water. Gradually, Europe is confronted with that problem."

And now both sides have realized how interdependent they are, total trade volume reaching about 560 billion euros last year, up from 400 billion euros the year before.

"At the same time, (even though) we are very interdependent, we are also very different."

The differences in culture, political systems and basic values make mutual understanding difficult, to the extent even of trying to agree on what "core interests" means.

Geeraerts says China and the EU have to accept these facts and work from there to try to develop genuine, sustainable and mutually beneficial relations.

Nowadays both need structural changes. While China needs to make the difficult change from an export-oriented economy to a more consumption-oriented one, Europe needs to reinvigorate itself by developing stronger internal cohesion, regaining competitiveness and rethinking labor market and society models to make them more dynamic.

In developing a sustainable relationship, China telling Europe what to do or vice versa is not what it is all about, he says. "We have to both do our homework to make a sustainable relationship possible."

Evolving to a more innovative society that will demand very deep changes does not happen overnight.

"The common thing we are facing is that it will take time. (These are) not the kinds of changes you can do with a click of the fingers."

Geeraerts is keenly aware of the consensus that Beijing and Brussels need to tackle China's market economy status in "a swift and comprehensive way".

Geeraerts takes the first adjective in that formula, "swift", at face value, taking it to mean both sides need to discuss it as soon as possible. As for the "comprehensive", he takes that to mean Beijing and Brussels need to go beyond market economy status.

It indicates an awareness and willingness to try to find a solution, and to keep the relationship going so that everyone benefits, he says. At the same time, there is an awareness of the difficulties.

"Because for me, it is obvious that if China develops its domestic market, this will open opportunities for competitive European companies."

When China joined the WTO in 2001, China and the EU agreed that the latter would not grant Beijing full market economy status until it fulfilled a set of requirements. Nearly 100 countries have given China the nod, but the EU has refused, despite repeated requests by Beijing.

The EU bases its resistance on the fact that European businesses have become increasingly vocal about their alleged difficulties in gaining access to the Chinese market, about technology transfer, intellectual property issues, and access to public procurement.

Meanwhile, Chinese business people complain about difficulties in doing business and finding investment opportunities in European countries.

"In fact we are reproaching each other (over) similar problems. And there is a need to find some solutions."

He believes China will be granted market economy status anyway, and says there is strong symbolic value because China wants to be treated as an equal partner.

He also links possible quick action on the issue to the EU sovereignty debt crisis and China's willingness to help the EU with that problem.

For China, pitching in to help with the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the EU's bailout fund, is but one element.

Geeraerts says China wants to have the opportunity to invest more in hard assets such as industrial projects and infrastructure.

He says China is willing to help with a bailout, but wants solid guaranties that it will get its money back.

He says China's intention is that even if it is willing to put its money into the ESM mechanism, the IMF will be involved in tandem.

"As a European, I fully understand China's position. Why should China put in money and risk it if Europeans themselves are not eager to do it? It will be some kind of combination."

For China, Geeraerts says it is important because it shows its growing influence and it enhances its image as a responsible stakeholder.

"China is playing cleverly with pragmatism but at the same time it looks at the complete picture."

You may contact the writer at fujing@chinadaily.com.cn

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|