Three decades of athletes

Updated: 2012-03-09 07:34

By Tilde Lewin (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

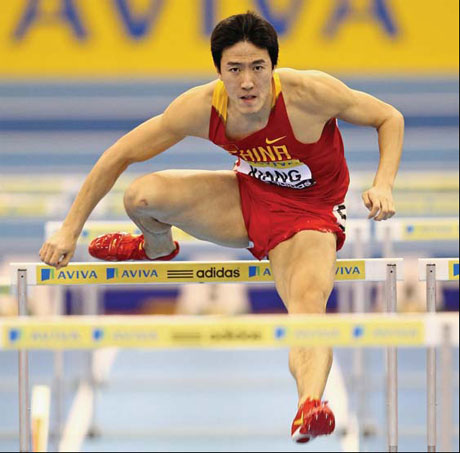

Liu Xiang in action during the Aviva Grand Prix at the NIA Arena on Feb 18 in Birmingham. Photos provided to China Daily |

From national heroes to pop idols

在过去三十年,中国的"体育健儿"们经历了从民族英雄到大众偶像的转变。

Chinese diving queen Guo Jingjing knew her worth. She made a demand worthy of a diva: "If you don't put me on the cover I'm not doing the interview."

In celebrity terms, she was not asking for much, just some wind in her hair and a chance to strike a flirty "Cosmopose" - signature moves that come naturally to regular cover girls like Kate Hudson and Sarah Jessica Parker.

It is not just Guo Jingjing. Hurdler Liu Xiang did endorsements for Cadillac and tennis player Li Na was a Rolex spokesperson.

Chinese sports stars are getting very glamorous. Aren't Chinese athletes supposed to pose in troop-formation, wearing identical sportswear, giving off the idea they are thinking about nothing but their resolve to win glory for the nation who trained them? What happened?

At first, international competitions were not just "games." Around the time of the Opium War (1839-1842), China became known as "the Sick Man of East Asia" (东亚病夫 dōngyàbìngfū). Even after 1949, the Chinese felt the lasting humiliation of history, so they saw strong, skillful athletes as part of a refreshed national image.

The first Chinese Olympic gold medal was won in 1959 by Hong Kong ping-pong player Rong Guotuan. He catapulted to fame. When he disembarked after his flight from West Germany, Marshal He Long greeted him.

|

Guo Jingjing shows up at a fashion show in Beijing. Photos provided to China Daily |

Later, he met Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai in Zhongnanhai. He was invited to dinners with foreign diplomats. A cinema manager, after recognizing Rong in the theater, asked the audience to stand up so that the shy young man could give an impromptu address in front of the big screen.

Zhou Enlai summarized that year as one of "shuangxi", double happiness: one happiness being New China's 10th anniversary, and the other Rong's win. This became the namesake for a ping-pong equipment brand, "Red Double Happiness (红双喜, hóngshuāngxǐ)". Marshal Chen Yi drew parallels between legends past and present.

"In ancient times we had national heroes like Yue Fei, who sacrificed himself to protect his country. Now athletes are our new national heroes; they win glory for the country."

However, when their performances became a point of national glory, the new national heroes found themselves in precarious positions.

When gymnast Li Ning returned home from the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics with five medals, he rode in on a bandwagon. He was greeted by festive crowds and firecrackers everywhere.

Just four years later, at the 1988 Seoul Olympics, the 14-time world champion slipped from the rings and fell from the pommel horse. Now the media broadcast harsh criticism. When he arrived, he had to leave the airport through a side exit to avoid the angry public. Hate mail came in; some people even sent knives, nooses and letters asking Li Ning to kill himself.

Apart from the emotional masses, there were also severe systemic pressures. Rumors of strict training regimes unraveled into public scandals.

The public's demand for national glory bred sporting sensations, like the miracle female long-distance runner team known as Majiajun (马家军, "Ma's family army"). These women won gold medals and broke world records in the early 1990s, but later media reported that they were living under harsh conditions, such as being ruled by cruel, despotic coaches.

Their legendary head coach Ma Junren is featured in a Wikipedia entry, which ends with the curious line that though Ma has retired from training Chinese athletes, he now spends all his energy training Mastiff dogs.

So when did Chinese wake up to their national heroes becoming advertisements for fancy cars and luxury accessories? The women of the Majiajun were not even allowed to own make-up, much less pose on fashion magazine covers.

Perhaps it happened when the economy woke up with an itch for domestic market demand.

Chinese athletes today may still represent the dreams of a nation, as they did in the early days: today they are the face of the Rolex dream; they represent the glorious market transformation of this country.

As China wins over in other global arenas, athletes have been relieved of the burden of earning national glory. They are human again, free from their predecessors' fate of "sheng ze wang, bai ze kou (胜则王,败则寇。He who wins is king; he who loses is but a bandit)."

When Liu Xiang limped off the field at the Beijing Olympics, there was some sulking, but no knives came in his mail. Instead of demanding his self-sacrifice, fans cried, "We don't want the medal; we just want you to be well."

To a large extent, Liu Xiang had already served his role as the poster boy for the Games. Nobody doubted that he was a national hero. Who could, after seeing him flash his megawatt smile on billboards and TV spots wearing the Chinese colors?

At last year's Winter Olympics, speed skater Zhou Yang said in an interview after winning gold: "I want to thank my parents ... I want them to live a better life now that I am a gold medalist."

Yu Zaiqing, vice-chairman of China's General Administration of Sport, responded that she should put her gratitude to the country before that to her parents.

This time, the people's outrage was directed at Yu. A CCTV host retorted, "It was her parents who took her home on a bike after training, and her mother who cooked for her.

"Why should she thank some leader who only knows of her existence after she became a medalist?"

In the end, Guo Jingjing on the cover of Cosmopolitan represented a hybrid of a catwalk model and a model worker. There is the swagger, the hand on the hip, but then she is also a bit too stiff, and the way she seems to hold her breath makes you think she was inspired by the love of her glorious nation after all, rather than of the expensive garments draped across her limbs.

A friend who worked at Cosmopolitan's China edition at the time said it best: "She looks a little wooden (她看起来有点木。 Ta kan qilai youdian mu)." She is right.

Guo Jingjing does not really fit the part, but it is because she, like other contemporary Chinese sports stars, was trained by the same establishment that created their predecessors. Now, however, the successful ones also have advertising dollars (or rather, renminbi) thrown at them with the ferociousness of a revolution.

Thirty years on, in the sporting arena, there is a little less idealism, a lot more brands, and voila: a Cosmopolitan cover with Chinese characteristics.

Ginger Huang contributed to this story.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|