Alice and the dragon that wants to fly

Updated: 2012-03-09 08:37

By Markus Eberhardt (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Analysis of patent applications throws some light on how China is faring

China's economic success over the past three decades has traditionally been viewed as the result of its ability to produce manufactured goods at low cost. Lately, however, the country has appeared to be catching up fast in scientific and technological innovation.

Between 1999 and 2006 the number of domestic invention patents filed with China's State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) rose at an average of 32 percent a year, from about 15,600 to more than 122,000. By way of comparison, the average annual growth rate of patents filed by US residents with the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) was just 6.5 percent.

China's impressive figures are backed up by bold forecasts. The current 10-year National Patent Development Strategy, for example, predicts Chinese patent applications will almost double between 2010 and 2015.

But what do these remarkable statistics and stirring statements of intent really mean? To find out it is essential to discern what really lies behind the recent explosion in Chinese patents.

A new study published by the Globalization and Economic Policy Centre (GEP), based in Britain at the University of Nottingham's School of Economics, aims to make sense of this puzzle. It uses a groundbreaking approach to analyze a dataset of about 20,000 manufacturing firms registered in China from 1999 to 2006, examining patents they filed with SIPO and USPTO between 1985 and 2006 to chart the growth in applications and investigate the reasons behind it.

Whether companies seek protection only in China or in both China and the US is crucial to assessing the nature of patents and the decisions behind them, since the direct and indirect costs associated with patent protection in the US are higher, as is the "novelty hurdle" in the patent examination.

The analysis may have been painstakingly complex, but the findings are unambiguous. The top 10 Chinese companies filing with SIPO during the sample period accounted for more than 75 percent of all patents, while the top 10 Chinese firms filing with USPTO accounted for about 85 percent - and many of the same companies dominate both lists.

In other words, the Chinese patent explosion has been driven by a small group of genuinely global players that, as their USPTO filings attest, are highly integrated into the worldwide economy. The firms patenting in both China and the US are big, young, more R&D-intensive than their peers, largely export-oriented and, above all, have a strong focus on information and communications technology equipment.

This is the unequivocal explanation that the ever-intensifying debate surrounding China's innovative prowess and potential development path has previously struggled to supply, and it has important implications for policymakers not just in China itself but around the world.

At this point it is worth pausing to re-examine the opposing sides of the debate. These can be neatly summarized as the "Red Queen run" and "middle-income trap" scenarios.

The first term was coined by Dan Breznitz, an associate professor at the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs, in his recent book on China's phenomenal growth. Breznitz was in turn inspired by the Red Queen in Alice in Wonderland, who remarked: "Here it takes all the running you can do to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else you must run at least twice as fast as that." The contention is that China's ability to stay close to the global technology frontier by improving on and adapting existing innovation -indeed, by running as fast as it can - is key to the country's enduring growth.

More pessimistically, there is a school of thought that warns that without the domestic development of genuinely novel product innovation China risks falling into the same middle-income trap that some commentators argue has already claimed developing nations such as Malaysia. This, the theory goes, is the price to pay for failing to make the vital leap from labor-intensive to knowledge-based economy.

The reality, according to GEP's analysis, is to be found somewhere between the two extremes. Contrary to the terms of a bona fide "Red Queen run", some Chinese companies do appear to be truly innovative, potentially even pushing the global technology frontier in certain niches; and yet there are precious few, and some of the most active are foreign-invested.

This corroborates the oft-leveled criticism that most of the innovation in China is merely incremental in nature and that the corresponding patents therefore protect only what have been described as "small inventive steps" rather than substantive new technologies. Although it might still be of value, this form of piecemeal innovation clearly embodies little technological progress and remains open to accusations of being driven mainly by incentives put in place by the Chinese government to encourage patenting directly.

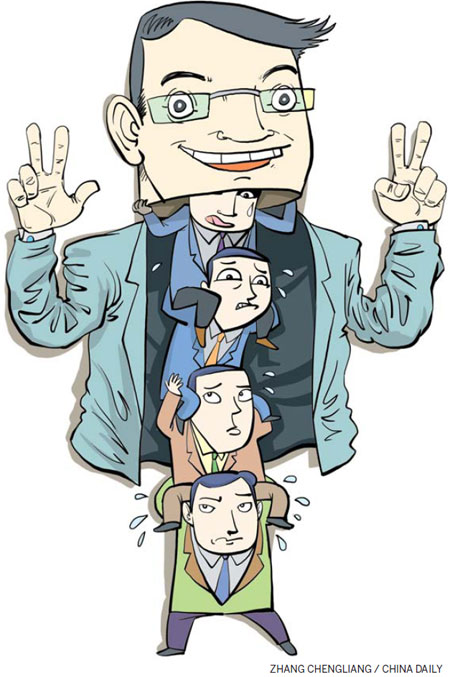

It is easy to get excited about hefty percentage increases and audacious estimates, but that excitement is duly tempered when the facts are fully appreciated. The firms responsible for China's patenting explosion do not represent the spearhead of a larger group of companies, poised to lead the Chinese economy to a wider technological take-off: they merely reflect an exceptional and highly select group that is unlikely to herald a broader underlying leap.

The truth is that we are talking about the success of a particularly small group within a single industry. Chinese patenting is concentrated in very few sectors, and even within these it is undertaken by very few firms, albeit highly active ones.

The sensible conclusion must therefore be that Chinese companies, for now at least, are likely to focus on incremental process innovation. GEP's research supports the suggestion - some might even say the fear - that for some time yet most firms are unlikely to turn their attention and their talents to "new-to-the-world" technology.

The findings may well point to China eventually becoming an economy that competes not only on cheap labor and sheer scale but also in terms of innovation. However, as with other successful Asian economies at the corresponding point in their development, the basis for China's transformation from imitator to innovator is relatively thin, with just a few authentic global players.

The dragon may be flapping its wings, but it is not flying just yet.

The author is a lecturer at the Nottingham School of Economics. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily 03/09/2012 page8)

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|