Unpopular but friendly advice

Updated: 2012-02-17 07:50

By Cecily Liu and Zhang Haizhou (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

Martin Wolf says he sees a soft landing as China's growth slows and remains above 7 percent this year. Zhang Haizhou / China Daily |

Economics expert says events have proved him right

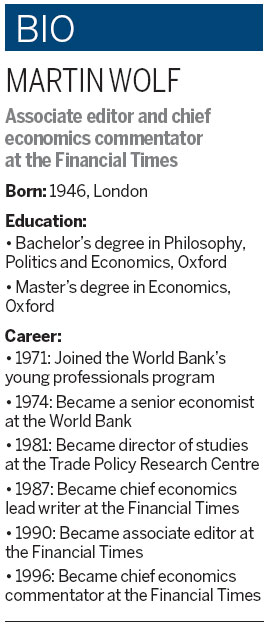

Martin Wolf, associate editor and chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, has on his desk a souvenir Chinese terracotta warrior and a miniature of French sculptor Auguste Rodin's Le Penseur.

These two classic works of art catch the eye among the neatly stacked shelves of financial books in Wolf's spacious Thames-side London office. But together they hint at a more current story - China's amazing economic growth alongside the anxiety caused by Europe's debt crisis.

"I expect Chinese foreign investment in Europe to grow substantially over the next 10 or 20 years, and that's quite natural and normal," Wolf says.

In the past two months alone, China Investment Corporation, the country's sovereign wealth fund, bought an 8.68 percent stake in the UK's largest water and sewerage company, Thames Water, while China Three Gorges, the operator of the world's biggest dam, bought a 21.35 percent stake in Portugal's biggest power producer, Energias de Portugal SA.

"Europe is still rich and has lots of high-technology companies," says Wolf, adding that further opportunities for Chinese investment exist in the motor vehicle, civil aviation and financial services sectors.

The relationship between China and Europe changed significantly in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. The same financial shock that exposed the unsustainable debt levels of some eurozone governments left China's growth almost intact - thanks to a 4 trillion yuan ($635 billion, 483 billion euros) stimulus package introduced by the Chinese government, the effectiveness of which "really surprised" even Wolf.

|

More than two years after signs of the eurozone crisis first emerged, European leaders are increasingly calling for help from major emerging economies. China, with its $3.2 trillion foreign exchange reserves, is especially seen as a potential white knight.

Wolf disagrees. "I don't think China can save Europe from the crisis, unless it uses up all of its reserves for that purpose, which would be crazy, because they want to keep it for China."

A forum fellow at the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos since 1999, Wolf has been named in the list of the top 100 global thinkers by British magazine Prospect and by American magazine Foreign Policy.

After studying economics at Oxford, Wolf joined the World Bank's young professionals program in 1971, but quickly became disillusioned with the bank's inward-looking policies.

Arguing that the bank's efforts were either "unnecessary or wasteful" in his 2004 book How Globalization Works, Wolf wrote: "I came to the conclusion that borrowers fell into three categories - those that did not need the help; those that would not use the help; and those that needed the help and would use it. The bank was constitutionally incapable of concentrating its efforts on the third, often quite small group."

But looking back, Wolf says that he would not "beat the World Bank anymore", because most emerging markets are now integrated into the world's capital markets, and the bank's power as "more or less the only external funder of size for most developing countries" back in the 1970s has greatly diminished.

Wolf left the World Bank in 1981 to become director of studies at the Trade Policy Research Centre, in London. Coincidentally, this decision to leave the bank meant that it did not include him in its famous first mission to China in the fall of 1980. Attended by 32 World Bank specialists, and received by a Chinese team headed by a "young Chinese economist" named Zhu Rongji, who became Chinese premier in 1998, the event marked a watershed moment for the economic opening of China.

Thus, Wolf's first visit to China was delayed until 1993. He recalls that back then Shanghai and Beijing were still full of bicycles, and their facilities, including airports, were primitive.

"The changes are just unbelievable," says Wolf, who has witnessed how Beijing and Shanghai have grown in the past two decades to be covered in skyscrapers like London and New York.

By 1986, the Trade Policy Research Centre had run into financial difficulties, but luckily Wolf was invited in 1987 by the then Financial Times editor, Geoffrey Owen, to join his team. Although Wolf had never considered a journalism career until then, he took on the challenge and is now widely considered one of the world's most influential writers on economics.

Former US secretary of the treasury Lawrence Summers called him "the world's pre-eminent financial journalist", while economist Kenneth Rogoff has said, "He really is the premier financial and economics writer in the world".

But Wolf downplayed these comments: "I do my job as well as I can."

Befitting someone who writes for insiders, his style is brazenly dense. His FT columns come with footnotes and charts. "Since I only have a small number of words, and there's a lot to say, I try to write it in a fairly compressed way," he says.

Among Wolf's circle of close friends are influential economists, bankers and policymakers, including Chinese economist Yu Yongding, of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

The two friends hold similar views on China's economic policies. But if their shared pessimism about China's unsustainable trade surplus and foreign exchange reserves were unpopular a few years ago, problems with China's rising inflation and asset price bubbles that emerged recently have led more people to accept their argument.

"One thing that is clear, absolutely clear, is that the export growth that China had in the years leading up to the crisis will never happen again," Wolf says.

Last year, the Chinese government placed domestic consumption rather than export growth at the heart of its 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015). The renminbi appreciated by about 5 percent against the US dollar in 2011 and the country's foreign exchange reserves fell to $3.18 trillion on Dec 31 from $3.2 trillion on Sept 30, the first quarterly drop since 2008.

Wolf took these changes as evidence that his views on China's economy have been proved right. "So I feel, though I may have been a bit unpopular, it was friendly advice," he says.

As China's growth slows, Wolf sees a soft landing. "That is to say, growth will remain above 7 percent this year, but I don't think you can rule out the possibility that there will be a temporary lowering in growth," he says.

He gives one example - an increase in consumption will result from increases in household incomes, but increasing wages would reduce companies' profit margins, deterring further investment.

"In the process of shifting income to households, there is a risk that investment will fall too quickly, and the resources available to be invested will be squeezed," says Wolf, who adds that he has confidence in the Chinese government's ability to stimulate growth should private sector investment drop abruptly.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|