Thinking locally, managing globally

Updated: 2011-08-12 11:01

By Paul W. Beamish (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|

To understand the challenges for Chinese companies entering foreign markets, it is important to first establish the requirements for competing globally, and then evaluate whether Chinese enterprises' strengths align with these requirements.

Let's first look at the history of internationalization. Western companies started with the logic of "thinking internationally and acting domestically" by leveraging their domestic advantages worldwide. Correspondingly, they adopted a center-for-global innovation model - sensing new opportunity in their home country, and driving the innovation through their overseas subsidiaries.

Then this logic evolved to "thinking globally and acting locally", viewing the world as a single unit of strategic analysis while managing overseas subsidiaries as a decentralized federation. The center-for-global model was upgraded to a local-for-local one - subsidiaries used their own resources and capabilities to create innovative responses in local markets.

Multinational enterprises are now committed to "thinking locally and managing globally" by proactively responding to both local needs and global demands and managing overseas subsidiaries as an integrated network.

They develop a globally linked innovation model to pool the resources and capabilities of diverse units to create and manage an activity jointly. To achieve these transitions, Western multinational enterprises have devoted substantial efforts and endured many difficulties and failures.

Judging by revenues, many Chinese enterprises are already world-class players. On the Fortune Global 500 this year, 61 enterprises based in China are listed, but only two of them are privately owned; the majority continue to be Stated-owned enterprises. In contrast, the largest counterparts from the West are private multinationals, each with many foreign subsidiaries across the world.

In response to the Chinese government initiative to go global, Chinese enterprises have begun expanding their entrance to foreign markets.

China's overseas direct investment (ODI) flow reached $56 billion (39.5 billion euros) in 2009. Yet Chinese ODI only accounted for 6 percent of the global ODI stock in 2009. Mostly limited to the downstream of global value chain in areas such as low-cost production, Chinese enterprises' ODI activities are often directed by the government, especially for those deals involving oil, minerals telecommunications, which are still required to remain under government oversight.

This suggests that Chinese enterprises have initiated the first step - to think globally but mainly act domestically. Some of them are struggling to act locally, but overall, most have yet to develop a transnational perspective with the corresponding business strategy to think locally and act globally. Such an approach is fundamental to sustain and thrive in international markets.

Having been accustomed to government direction, do Chinese enterprises have the necessary strategies to compete globally? When considering this question, Chinese executives generally present two arguments - they have strategies that are government-directed, and the strategies originating from their Western counterparts are not applicable to China. Neither of them hold much water.

With regard to the first argument, government-direction deserves some merit as a domestic strategy - the government concentrates resources to the selected enterprises, and tries to cultivate them into world-class players. However, government direction encourages Chinese enterprises to compete for resources mainly by leveraging their relationships with the government. Those bonds don't fit well with most foreign markets, as they are embedded in a completely different institutional environment where government is just one stakeholder with constrained power in shaping business decisions.

Moreover, with the government's protection, the chosen enterprises lack experience with market competition to develop their core competences, and the necessary managerial and governance techniques for going global. Chinese multinationals have to stretch beyond such reliance on government relationships to develop new skills to utilize a management with multiple stakeholders, as it is essential for business survival in global markets.

With regard to the second argument, imitation of any specific business strategy usually does not lead to a competitive advantage. But the fundamentals of strategic management transcend national borders, and they can be applied with appropriate adaptation to fit the local context. When Western enterprises first entered the Chinese market, many suffered from the same "silver bullet" confusion, and paid dearly to realize that an exact replication of their domestic strategies was unworkable.

They then started to invest their resources in gaining insights from the local environment, and hence Western management academia now cover Confucianism and guanxi, the exchanging of favors.

This is the evolution of globalization. Globalization does not mean imposing homogeneous solutions in a pluralistic world, regardless of their sources. It means having a global vision and adapting to local variations resiliently. The question for Chinese enterprises entering global markets is how much of an effort they are willing to spend to learn from foreign markets?

Chinese enterprises have been actively pursuing overseas acquisitions as a route to gain advanced technology, manufacturing processes and global brands. However, it is still questionable whether such big-ticket purchases will help them leapfrog the necessary stages of competency development. Explicit knowledge, such as process management, supply chain efficiency, foreign countries' laws and rules, is relatively easy to learn. It is much more difficult, however, to leverage these principles without appreciating the underlying values and cultures.

Cultural know-how is a prerequisite to grasping local market demand and a source of inspiration to innovate or diversify local services. There are several reasons why Chinese companies are not paying sufficient attention to learning about local markets.

Chinese enterprises have not realized how important it is to respond to local values while carrying the weight of government and national expectations. In order to reach a financial breakeven point as soon as possible, they prefer the safety of sticking to their domestic approaches in foreign markets, and many do not tolerate the constructive conflicts or occasional failures that are inevitable part of the learning process.

In addition to learning from full immersion in foreign markets, qualified human resource departments are also critical. China is already home to several world-class management schools, and repatriates a substantial number of Chinese graduates of overseas MBA programs every year.

While the managers of Chinese- and foreign-owned enterprises in China lament that they cannot secure managerial talent groomed with a global vision and international experience, many MBA graduates find opportunities in China that actually contribute their talent are hard to come by.

The pursuit of a MBA designation is typically motivated by an individual's career aspiration. The criteria and process by which future employers select and recruit new talent, however, substantially influence what and how job candidates learn in management schools. Many Chinese students are primarily interested in courses involving methods and best practices that can be readily applied to immediate business needs. The fundamental knowledge crucial to the honing of a global vision and the preparation for a creative mindset is not perceived as equally useful. The task-orientation reflects that Chinese enterprises are still placing greater emphasis on skills than abilities, and on operational efficiency than strategic effectiveness when selecting managers from the pool of raw talent.

Moreover, although networking is important in any market, Chinese MBA students emphasize it very heavily in regards to their future career paths. Executive MBA programs are even viewed by some Chinese executives as social clubs for creating new guanxi rather than learning opportunities. This tendency not only reflects that Chinese enterprises perceive networking or guanxi as managers' prior advantages, but also suggests that Chinese enterprises might not be as effective in identifying promising candidates, or developing individualized and long-term programs to cultivate the talent that can support their global expansion.

Chinese enterprises face a long road ahead in pursuing effective transnational management - thinking locally, acting globally, and innovating jointly. According to Sun Tzu, the classical Chinese strategist, "if you know yourself and the competitor, you will not lose the game". Before establishing their presence in the global marketplace, Chinese enterprises will need to upgrade their understanding of globalization, and then reevaluate what they know about themselves and what they should learn about others. They also need to appreciate the fact that a global vision and local insights are strategic objectives requiring great efforts and extensive investment of time to achieve. As a result, they will need to improve their managerial infrastructures, especially in strategic planning and human resource management, to facilitate long-term organizational learning.

Globalization has established much better global connectedness, such as Internet access, than ever before. Chinese enterprises may save themselves a lot of cost by learning from the experiences and mistakes their Western predecessors went through when entering foreign markets, including China.

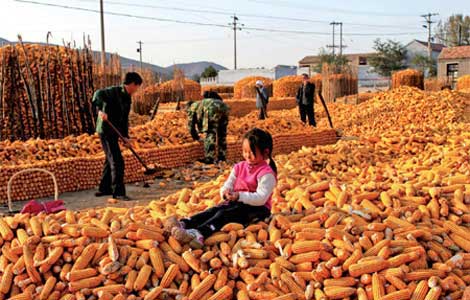

But there are no shortcuts, and setbacks are inevitable. No doubt there will be more Chinese enterprises on the Fortune Global 500 list, and China's ODI will keep rising. But China's labor and material costs are also soaring. Thus it is urgent for Chinese multinationals to cultivate their core competencies - the abilities to truly distinguish themselves from the other global players, before exhausting their low-cost advantage.

The author is a professor of international business at the Ivey Business School, University of Western Ontario, Canada. The opinions expressed in the article do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

E-paper

My Chinese Valentine

Local businesses are cashing in on a traditional love story involving a cow herder and a goddess

Outdoor success

Lifting the veil

Allure of mystery

Specials

Star journalist leaves legacy

Li Xing, China Daily's assistant editor-in-chief and veteran columnist, died of a cerebral hemorrhage on Aug 7 in Washington DC, US.

Sowing the seeds of doubt

The presence in China of multinationals such as Monsanto and Pioneer is sparking controversy

Lifting the veil

Beijing's Palace Museum, also known as the Forbidden City, is steeped in history, dreams and tears, which are perfectly reflected in design.