Understanding how China thinks

Updated: 2011-07-29 11:37

By Daria Berg and Mohammed Shafiullah (China Daily European Weekly)

Upholding harmony in the land is key to Chinese development

|

It was telling that Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao opted for culture over politics for the first stop of his recent visit to Britain. Speaking from the birthplace of William Shakespeare, he told of how literature and culture could act as a bridge between nations and implicitly chided leaders that sit at the negotiating table with little understanding of the history and culture of countries they are dealing with.

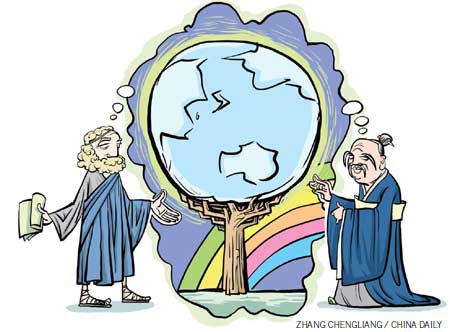

China and Europe have a lengthy history of miscommunication. If this gap of understanding is to be narrowed, European politicians and people must recognize how Chinese thought differs from the beliefs that are taken for granted in the West. Europe cannot seek to comprehend China without understanding China's past and its philosophical influence on Chinese psychology.

The exploration of just how far China and Europe are from "getting" each other has been carried out to great effect by two young Chinese artists known as "The Utopian Team". Utopia is Back was the title of an exhibition launched in Beijing by He Hai and Deng Dafei. It charted the artists' experiences during a three-month stay in Scotland and the birthplace of James Legge, one of Europe's first recognized sinologists.

Both He and Deng are members of China's Generation X: children born in the mid-1970s who grew up during Deng Xiaoping's era of reforms and witnessed the transformation of Chinese society into a land of super-sized economic growth and new consumer delights. China's Generation X has emerged as a new group of consumers with fresh visions of what constitutes the ideal society in the 21st century - the modern utopia.

The work of the Utopian Team serves as a useful case study for exploring how the concept of utopia is ingrained in the Chinese psyche and the collective memory from the past. By presenting the Chinese ideology of utopia to Europe, the artists reveal much about how the Chinese think and show that the contemporary Chinese vision of utopia derives from ancient ideals such as the Confucian search for harmony.

Utopia may be a Western concept that stems from a pun on the Greek words for "nowhere place" and "happy place". It denotes an ideal society in Thomas More's 16th-century book Utopia (1516), but the concept has a Chinese equivalent with roots in traditional Chinese culture.

China has been the land of many utopian visions from ancient to modern times and the search for utopia in China has spilt much ink and blood. The Confucian utopia of the Great Sharing (da tong) stems from the ancient Confucian classic The Book of Rites.

The idea of the realm of Supreme Harmony (tai ping) goes back to the ancient Taoist philosopher Zhuangzi (369-286 BC) who lived during the Warring States period (403-221 BC) before the first unification of China in 221 BC.

Another vision of utopia, the land of Huaxu, is a realm of perfect order and prosperity that China's legendary Yellow Emperor, the founder of Chinese civilization, was said to have reached in a dream; he subsequently strove to govern his empire on its model.

There have been many more visions of utopia throughout the centuries, from the Taiping rebels in the 1860s to the founding father of Republican China Sun Yat-sen, and the leader of New China Mao Zedong.

What binds together Chinese visions of utopia is the importance of upholding harmony in the land, an ideal that occupies center stage in Chinese President Hu Jintao's contemporary political doctrine of the "harmonious society".

Harmony is based on the ancient Chinese concept of zhong yong, the "Doctrine of the Mean", as expounded in the eponymous Confucian classic. Zhong yong, also translated as "midway thinking", advocates moderation and modesty with the aim of creating harmony in interpersonal relationships. It is the Chinese way of solving social conflicts.

According to China's current leaders, a harmonious society puts people first. The People's Daily newspaper in China describes "harmonious society" as a scientific concept of development to help solve contradictions and conflicts in China's transformation period while maintaining social harmony, progress and stability.

Xiao Zhuoji, professor of the School of Economics of Peking University, explains: "In a harmonious society, the political environment is stable, the economy is prosperous, people live in peace and work in comfort and social welfare improves."

The idea of harmony also governs China's international relations, as Hu Jintao stressed during his visit to the US in January. China's Premier Wen Jiabao told Britain during his recent visit: "Tomorrow's China will be a more open, inclusive, culturally advanced and harmonious country."

The search for harmony extends not only to politics but to culture, too. China's State Councilor Liu Yandong notes that the concept of harmony regulates relations "among peoples, between individuals and society, among nationalities and states, among cultures and between humans and nature." She stressed the need to "promote multinational cultural communication under globalization".

This is where the Utopian Team comes to the fore. Through a combination of avant-garde art and a social consciousness they strive to promote cultural communication between China and Europe.

Like many of the new generation of writers, artists and intellectuals in China, He and Deng critique local culture, the impact of globalization and the spectacular transformation of urban life in China today. Their 2008 work "Family Museum Project" tackled social issues such as poverty and the plight of the migrant workers in Shanghai. More recently they rolled a huge ball of red thread through the streets of Guangzhou to symbolize the disorientation felt by new migrants in the city.

As part of the Utopia is Back project, He and Deng visited Scotland in 2009 to perform an artistic memorial to the Scottish missionary and pioneering 19th Century sinologist James Legge (1815-1897). Legge gained fame for his translations of the Chinese classics, such as The Doctrine of the Mean, into English. In 1876 he became the first professor of Chinese at Oxford University. His mission was to gain insight into Chinese thought while giving Europe a better understanding of the Chinese world.

The Utopian Team sought to reciprocate James Legge's journey to the East by embarking on their own journey to the West, building new bridges of understanding and opening new channels of cultural communication between China and Europe.

The Utopian Team's most spectacular performance event in Scotland was a parade through the streets of Legge's birthplace, the Scottish market town of Huntly in Aberdeenshire. The event dramatized both the celebration of intercultural communication and the pitfalls of cultural misunderstanding. The artists staged a symbolic funeral procession in memory of Legge, part mourning ritual, part carnival celebration.

By interweaving Chinese and European languages, symbols and imagery, the Utopian Team achieved an event that is perceived as a carnival by some, but a memorial event steeped in religion by others. Chinese calligraphy, traditional Chinese white funeral attire, and newspaper confetti as money of the underworld intermingled with the sounds of Scottish accents, bagpipes and Christian hymns.

The Utopian Team's artistic activities demonstrate that global communication requires us to strive for a profound understanding of each country's social and cultural contexts. He Hai notes: "Just as James Legge did in China, we tried to integrate completely into the life of Huntly - we were trying to change into local people."

Their work reminds us that reaching a societal utopia lies in bridging the communication gap between East and West; in tackling the social challenges that the new generation of China's citizens face; and in contributing to a truly harmonious society of the future.

About the authors:

Daria Berg is an associate professor of Chinese Studies at the School of Contemporary Chinese Studies and the China Policy Institute at the University of Nottingham.

Mohammed Shafiullah is Senior Lecturer in Psychology at the Division of Psychology and the Centre for Intercultural Research in Communication and Learning at De Montfort University in Leicester.

E-paper

Double vision

Prosperous Hangzhou banks on creative energies to bridge traditional and modern sectors

Minding matters

A touch of glass

No longer going by the book

Specials

Carrier set for maiden voyage

China is refitting an obsolete aircraft carrier bought from Ukraine for research and training purposes.

Pulling heart strings

The 5,000-year-old guqin holds a special place for both european and Chinese music lovers

Fit to a tea

Sixth-generation member of tea family brews up new ideas to modernize a time-honored business