Strategy for brand-building success

Updated: 2011-05-27 10:58

By Mike Bastin (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|

Brand-building nowadays involves an increasing combination of many success factors, however far too many companies (especially Chinese companies) rush into the tactical details way too soon. For example, they focus on what they think are brand-building advertisements or logs or sponsorship deals; a very common trap. This article highlights the need for strategic thinking when building brands and examines one of the key elements in any brand-building strategy: The brand name.

Brand naming strategies vary from corporate branding through to individual product brand naming as well as many combinations in between. The following provides a summary of the common approaches:

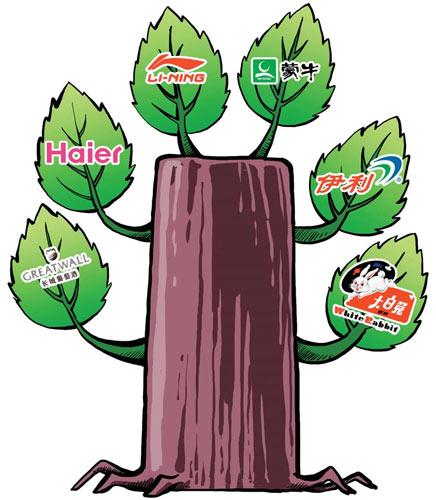

Corporate branding: Here the company chooses to promote its name only across all of its product brands. If the company's product brands are diversified then this form of brand strategy is also referred to as umbrella branding. Haier, Sony, McDonalds and Virgin all follow this approach. Despite Haier's diversification across household appliances from fridges to washing machines and air conditioners and their more recent move into mobile phones, they continue to pursue corporate branding. Of course the immediate advantage of this approach is speed and low cost, however long term this approach may lead to a lack of creative and critical thinking and severely inhibits repositioning, diversification and emotional differentiation. McDonalds now find it extremely hard to move away from the "hamburgers", "fast food" and "unhealthy" image, for example.

Unfortunately, this remains a defining feature of Chinese company brand strategy with Yili (one of China's leading dairy products producers from the Inner Mongolia autonomous region), Wahaha (Hangzhou-based soft drinks and fruit juice producer), TCL (Shenzhen-based consumer electronics producer), and Li Ning (Shanghai-based sports shoes, clothes producer), as well as Haier all pursuing corporate branding. While this may appear successful in China (but probably not for much longer) it certainly will not resonate with consumers outside China where the companies are still not that well known.

Product branding: This represents the complete opposite of corporate branding, where each individual product is given an exclusive brand name and little or attachment of the corporate name is promoted. Unilever and Proctor and Gambol both follow this approach with many world famous product brand names, such as P&G's Head Shoulders shampoo brand. One of the few examples of Chinese product branding is Da Bai Tu (which means "big white rabbit"), China's leading brand of sweet produced by Shanghai-based Guan Sheng Yuan Food Ltd.

Clearly, this approach will require more time and sustained, high levels of investment, however it offers unlimited product diversification and emotional differentiation opportunities. Chinese companies, or rather the senior management within these companies, need to resist the temptation of short-term gain that may result from corporate branding and invest long term in individual product brands. A cursory glance at P&G's diversified product portfolio supports such resistance.

Two-tier or double banding: This approach combines corporate and product branding where the company name and an individual product brand name are both promoted and displayed prominently. This is often the first step companies take when moving their strategy away from corporate to product branding. For example, Mengniu (one of China's largest dairy products producers, base in Inner Mongolia) continues to follow corporate branding but recently introduced a premium brand of milk with an exclusive product brand name, Telunsu. At the moment though Telunsu is promoted with the company name and not on its own such as Head and Shoulders. If this approach is taken then companies have to decide which is more important, the company name or the product name? When the product brand name is new it is often the company name that serves as more important role which is often referred to as source branding. Over time, however, the product brand name often becomes more familiar in which case the company name acts as a reminder only which is often referred to as endorsement branding.

China's leading car producer, Changchun-based First Automobile Works (FAW) can boast success here with their Hongqi (Red Flag) brand of business car, often the car used on official business by China's leaders. The FAW-Hongqi two-tier brand is also an example of how source branding often progresses naturally to endorsement branding over time.

Product-line or line-branding: Here products which are in the same product line appear under the same name, such as the different types of Coca Cola: Diet Coke (Coke Light), Cherry Coke, Lemon Coke, etc. This approach offers cost savings and speed over product branding and may be suitable where the product line consists of very similar product items, perhaps only differentiated by flavor or taste. Once again, however, such a lack of tangible differentiation may stifle product development. For example, many brand portfolios now consist of differing quality levels of the same product but can only achieve such perception in the mind of the consumer with a completely different name for each quality level presented.

Product-range or range-branding: Here a number of products across a broad product category are grouped together under the same brand name. Haier could consider, for example, introducing a range brand name for all of its household appliance products: fridges, washing machines and air conditioners.

In addition to brand name strategy and also of strategic importance is the meaning of the brand name chosen. The key issue here is whether the brand name should describe the product's functionality and/or use language that communicates some of the product benefits. The following provides a guide:

Descriptive brand names: These simply describe what function(s) the product actually fulfils, such as Agricultural Bank of China. Such names probably establish brand awareness more quickly and cheaply but lack creativity which may limit emotional differentiation. Business-to-business brands commonly adopt this naming approach, especially professional services companies such as legal and accountancy firms.

Associative brand names: These names use language which aims to communicate some product benefit, often emotional, such as Da Bai Tu (big white rabbit) a very successful Chinese brand of children's sweet. Nike, meaning the Greek goddess of victory, is also an example here. Wahaha, meaning "happy children", is also a good example of this approach. An excellent example of a foreign brand in China which uses this approach is Bambino Mio, the United Kingdom-based leading producer of cotton nappies. The name "Bambino Mio" means "my baby" is Italian, an excellent form of association given the stylish image most perceive the Italian language to have. This approach is demonstrably the growth area in brand naming, mainly because it enables much more innovative thinking and much-needed emotional positioning. Chinese firms need to take this approach much more seriously and make use of the rich source of associations that Chinese culture/history contains. While there are some examples, such as Great Wall (wine), there are many more opportunities here that could make use of China's famous mountains, rivers, festivals, etc.

Fictitious brand names: Language here has no real meaning at all and cannot be found in any dictionary, such as adidas and McDonalds. These names offer the advantage of ease of legal protection given their uniqueness, however considerable time and investment is then required to build brand awareness, brand image and brand association in the consumer's mind.

Finally, as more and more companies and their brands venture overseas it is also important to consider a brand name's meaning when entering countries which have a different language. Companies need to choose between a completely new name or some sort of translation or transliteration of the current brand name. Transliteration, which preserves the sound only, is often preferred as this requires little or no brand awareness building. Translation, preserving the meaning, is nearly always the case, however, when the name contains a real word, such as Apple is translated into the Chinese for "apple", or Ping Guo.

Some brand name representation may involves both translation and transliteration, for example Starbucks which is known as Xing-ba-ke, where Xing is the Chinese for "star" and ba-ke is a transliteration of "bucks". In China, therefore, Starbucks lose some of their positive association from the "bucks" (money) part of their brand name. While transliteration preserves the sounds only, it will always result in some form of meaning depending on the Chinese characters used. When entering China, therefore, companies with fictitious brand names (as perceived by the Chinese) need to move very quickly to ensure positive, associative transliteration. Successful examples include: Carrefour which has been transliterated into Jia-le-fu, which together approximates to "happy prosperous family". Coca-Cola also enjoys very positive representation with Kekou-kele which means roughly "happy, delicious taste", and the same is true of Subway with the transliteration Sai-bao-wei whose characters represent "better than 100 flavours".

Coca-Cola, however, did learn the hard way. When they first entered in China in 1928 many of the Chinese shopkeepers were quick to use any combination of characters which produced their exact transliteration "ko-ka-ko-la", they performed an exact transliteration unlike the current version. As a result, various versions, therefore, soon emerged for Coca-Cola's brand name is Chinese characters such as: "female horse flattened with wax" and "wax-flattened mare" and "bite the wax tadpole".

The above serves as a guide not just for Chinese companies on their path towards successful brand development but also to foreign companies aiming to build strong brands in the minds of Chinese consumers.

Having worked with Chinese companies, on all aspects of brand management, since the 1990s I foresee a very bright future for Chinese brands. The tide is definitely turning. It is time for the Chinese brand.

The author is visiting professor of brand management at China Agricultural University and teaches marketing and management at Tsinghua University.

E-paper

Thawing out

After a deep freeze in sales during the recession, China’s air conditioner makers are bouncing back

Preview of the coming issue

Cool Iron lady

Of good and evil

Specials

Memory lanes

Shanghai’s historic ALLEYS not just unique architecture but a way of life

Great expectations

Hong Kong-born singer songwriter rises to the top of the UK pops.

A diplomat of character

Belgian envoy draws on personal fascination to help build China ties.