Ring master

Updated: 2011-04-22 11:17

By Andrew Moody (China Daily European Weekly)

"While it might be directly comparable, it is interesting to read about the development of classical music in the United States in the 19th Century. There are very strong and interesting similarities. Local citizens, often wealthy people, became the patrons of orchestras because they wanted to bring something to the local environment and it became very commercial," he says.

|

"I think if you look ahead in 50 years' time this will be one of the most dynamically productive laboratories for culture of all kinds."

He says China is very different to emerging economies like India, where there is very little of a Western classical music tradition.

"One explanation is that India has such a rich musical tradition of its own which in a sense is like classical music with its virtuosi sitar players and dance tradition," he says.

"In China music has always been associated with temples or theater and while it had popular appeal, it didn't have much of an intellectual or spiritual appeal."

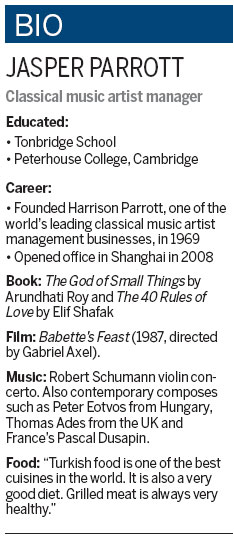

Parrott was born in Sweden but his father was British and his mother, Ellen (who is 100 this year), Norwegian and they all moved to the United Kingdom when he was four.

After Tonbridge School and Peterhouse, Cambridge (where his contemporaries among others included famous musical figures, the conductor Christopher Hogwood and early music director David Munrow), he started work in a travel agency.

He landed a position at Ibbs and Tillett, one of the leading classical music management businesses of that time before starting his own agency in London's Swinging 'Sixties. Such businesses traditionally just supplied artists for events but Parrott and his then partner Terry Harrison wanted to offer a more professional service, developing the careers of artists and commercially representing them, which appealed to younger performers.

"We had no offices and we all operated from our respective flats. The concept of the business was not just about cutting deals but supporting artists' recording activities and making sure they were present in most of the important markets," he says.

Western classical music in China dates back to the 19th century. The Shanghai Symphony Orchestra is the oldest classical orchestra in Asia and was formed in the 1870s and, although it originally played mainly to expatriate audiences, it also caught the imagination of Chinese people.

"I think classical music found a natural entry point and those people who were going to play a part in the modernization of China. They were people who were very much familiar with Western concepts of art and literature."

Western classical music took a big step back, however, during the "cultural revolution" (1966-1976).

"I am not an expert in the concepts behind the 'cultural revolution', such as they were, but I think it was about power and anything that was foreign was a bourgeois activity and must therefore be hostile to the interests of the people," he says.

"Western classical music, literature or anything like that were easy targets and so it was terrible. But it was also fantastic because there was enough tenacity, dedication and commitment from people who suffered to go on."

Parrott played a role in the revival of music when he first came to China in 1979 as part of a BBC program about the revival of classical music in the country.

By then many of China's greatest music teachers and musicians, who had been dispersed to the countryside, had returned to the cities.

"I came with Ashkenazy who did a series of masterclasses and conducted in a sort of barracks where there was a rehearsal hall. It was all very moving and extraordinary because they were bringing it all together again," he says.

He has since been involved in a number of landmark events on the music scene, including bringing one of the US' top orchestras, the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra, to China in the 1990s.

"They wanted to do a national tour and they wanted me to arrange it and it was a big challenge for us. The timing was perfect because it was before (then US president Bill) Clinton made his visit," he says.

"In those days there was no concert hall in Shanghai and the concerts here (in Beijing) took place in the Great Hall of the People, which is one of the worst places in the world to play classical music but it served its purpose well."

Parrott says the standards of China's orchestras are improving steadily over time.

"They don't yet rate much above the middle-level European, American or Japanese orchestras. When I first went to Japan many of the orchestras were quite modest but now they are very, very good," he says. "Most of the top orchestras in the world have one or two Chinese players in them now."

Parrott is one who believes classical music should be enjoyed and he is not one to complain about Chinese audiences being noisy with mobile phones having a tendency to go off at crucial quiet stages during a performance.

"It is true (that audiences can be noisy) but I think it is something to do with the way Chinese people view entertainment. I think artists like coming here. They feel a sort of visceral connection with their audiences," he says.

E-paper

Blowing in the wind

High-Flyers from around the world recently traveled to home of the kite for a very special event.

Image maker

Changing fortunes

Two motherlands

Specials

Models gear up car sales

Beauty helps steer buyers as market accelerates.

Urban breathing space

City park at heart of Changchun positions itself as top tourism attraction

On a roll

Auto hub Changchun also sets its sight on taking lead in railway sector