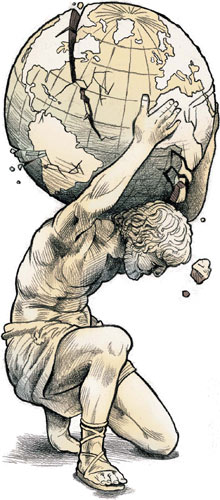

Tenuous hope for a eurozone recovery

Updated: 2011-04-22 10:36

By Ding Chun (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|

The quick answer is yes. The EU's economic self-interest and political will should combine to preserve the currency in spite of the difficulties ahead.

The EU sovereign debt crisis derived from the global financial crisis that divided Europe into northern and southern factions that are not completely based on geopolitics. The northern faction refers to countries that can become rescuers of the crisis: Germany, the Netherlands, Finland and France, which has a big say over EU decisions with its active role in the European economic integration despite its moderate economic performance.

The southern group refers to countries mainly located in southern Europe, including Greece and Spain, where the economic situation is fragile and in desperate need of help.

Not only are these southern European countries hindering the EU's economic recovery but they are also casting an ominous shadow over the global economic recovery. The debt crisis has evolved into a question of whether the eurozone is going to live or die and whether the EU's plans of integration should be carried out.

Although the 750-billion euro bailout plan in 2010 has prevented imminent danger, the sustainability of the sovereign debt hangs heavily over the prospects for economic and financial stability.

The EU is facing fundamental structural and governance flaws, such as the imbalance of fiscal and monetary policies and an imbalance in the levels of development of various countries. The short-term outlook for the southern countries is gloomy. The smaller economies, such as Greece and Ireland, are not going to recover anytime soon. For the larger economies, such as Spain, the sovereign debt crisis can blow up at any moment since their debt ratings are going downhill while financing costs are rising. In Portugal, the government has fallen from power.

The crisis has been exacerbated by a domino effect of debt. If Spain, the fourth largest economy in the eurozone which accounts for 12 percent of total GDP, were in trouble, the EU would find itself in a deeper hole.

But because the eurozone is in danger, the EU is discussing an emergency relief policy and a long-term solution to solve the sovereign debt crisis.

Looking at the crisis from the northern faction's perspective, if flaws in the financial system are not changed, southern countries will have to rely on the north for a long time. Germany's proposal calls for tougher fiscal discipline along with limited emergency financing at high interest rates. Countries with large deficits would be forced to make rapid and brutal adjustments. The plan lets southern countries contain the rapid increase in salaries, increase labor productivity, hike up the age of retirement, increase public income and decrease welfare expenses.

As Germany and other northern countries expand their scale of assistance to debt-riddled countries, they are also trying to keep the risk to them at a minimum. They have rejected European bonds, have insisted on relatively high lending interest rates and have demanded that Ireland and other countries cease what they call unjust and selfish measures, such as low corporate taxes.

These acts were meant to assuage the rage that has arisen among the public in the north that the north have done all the hard work through diligence while the south has slacked off. The acts were also meant to avoid any public opposition to the bailout plan. The efforts to enhance the EU's economic competitiveness, promote employment and consolidate and stabilize finances are called the Competitiveness Pact, which was first submitted by Germany and has gained approval from many northern countries, including France.

For the south, the pact is looked upon as economic suicide. Southern countries are hoping that the EU can issue united bonds in the eurozone, increase credit and establish a bailout system to lower financing costs for debt-ridden countries such as Greece and Ireland. They also want to avoid any further crises in Portugal and Spain.

Southern countries are endeavoring to gain from relatively low lending rates and avoid strict economic tightening agreements. They want to maintain a relatively low corporate tax rate in order to reduce the negative effects brought upon by tightening policies. After all, tightening policies are not good if countries want more public spending and an economic resurgence. They also want to keep public order during the crisis. The downfall of Portugal's government was the result of an indebted country clashing with its people. It is no surprise these southern countries are conservative and even against the strict Competitiveness Pact.

Despite major disagreements with the pact, leaders from both sides know that in order to stay afloat, they must maintain eurozone stability by helping indebted countries to overcome their current difficulties. Most of the sovereign debt is in the hands of banks in Germany, France, and the Netherlands. They are virtually in the same boat and they won't be able to afford the costs and responsibility if the European integration experiences a setback.

In March of this year, minor breakthroughs were achieved at an EU summit. A basket of bailout plans, such an agreement for the EU to extend credit from 250 billion euros to 440 billion euros, to carry out a bank stress test, and to establish a permanent bailout mechanism by 2013, were all hashed out in an effort to enhance the EU's competitiveness.

I believe these moves are steps in the right direction to alleviate the crisis. Non-eurozone countries such as Denmark, Poland and Bulgaria have recently said they hope to join the eurozone, which will boost confidence in the recovery at least in terms of market expectations. The moves also changed the attitudes of speculative investors.

For southern countries that are near crisis levels of debt (especially Portugal, which is in desperate need of 50 billion euros to 60 billion euros), the moves allow them some room to breathe. For northern countries, loosening lending conditions and slowing reform down are decent choices. If they insist on strict rescue conditions, the southern countries' economies could come crashing down again, which would lead to a eurozone breakdown. The aforementioned moves have in the short-term avoided economic crashes in southern countries and pushed long-term structural reform forward. They conform to the long-term goals set by 2020 and are real steps toward structural reform.

We should not expect the south to turn their economies around overnight. The gap in economic sustainability between the north and the south will be reduced temporarily, but over the long haul, the risk of sovereign debt crises reoccurring still remains if the fundamental flaws that contributed to the crisis - such as the lack of a unified fiscal policy and an insufficient welfare labor market system - are not fixed.

The author is the director of the Center for European Studies in Fudan University and the secretary-general of Chinese Society for EU Studies.

E-paper

Blowing in the wind

High-Flyers from around the world recently traveled to home of the kite for a very special event.

Image maker

Changing fortunes

Two motherlands

Specials

Models gear up car sales

Beauty helps steer buyers as market accelerates.

Urban breathing space

City park at heart of Changchun positions itself as top tourism attraction

On a roll

Auto hub Changchun also sets its sight on taking lead in railway sector