Welcome, new growth model

Updated: 2011-03-11 10:25

By Mark Williams (China Daily European Weekly)

|

Premier Wen Jiabao put price stability at the center of the government's concerns in his speech on March 5. So here is a question for deputies to the National People's Congress to ponder during their long hours in the Great Hall of the People. Why do so many families in China still struggle when prices of basic products rise?

The simple answer is that the incomes of many families do not stretch far beyond necessities. Especially with food prices rising rapidly over the past year, poor families are inevitably feeling squeezed. Though there are signs that inflation has not deteriorated in the last couple of months, it will be a while before the problem is totally eliminated.

The drought in northern China is raising questions, too, on how long grain supplies will last.

Besides, there is a great deal of concern, not just in China, over the soaring global price of oil. China is in a better position than most other countries to ride out that particular storm - though neighboring countries use half as much oil as China to produce a given amount of goods. But that is a testament not to Chinese efficiency but to the fact that its economy is hugely reliant on coal rather than oil.

It is not just oil prices that are high. The world price of soybeans, which China imports in vast quantities to process cooking oil and animal feed, has increased by more than half since the middle of last year. And global cotton prices are nearly three times what they were in mid-2010.

Still, it is not immediately clear why the level of inflation we are seeing today should be such a problem. Inflation of 4 or 5 percent is normal in many fast-growing emerging economies. In China, the average income increased more than 16 percent last year, much more than would be needed to compensate for the rise in prices. Stepping back, China's per capita GDP today is four times what it was a decade ago. Of course, consumers are never happy to see prices rise but there is still the question: Why are so many families struggling to make ends meet when incomes are rising fast?

The explanation lies partly in changing tastes and expectations. As we get richer, we get used to eating better food more often and are reluctant to change that habit. More important, though, is how little the lowest-income households have benefited from China's decade of supercharged growth.

The average income of the poorest families in Chinese cities has only doubled since 2000. That may sound reassuring until one realizes that food prices have increased by two-thirds during the same period. And when inflation is turning up primarily in the prices of food, as is the case today, these families are all the more vulnerable.

While the average family in China's towns and cities spends a quarter of its income on food, the poorest households spend close to half. So rising food prices hit the poorest households the hardest. Hence, it is not surprising that they are complaining.

What is to be done? Forget interest rates, even though this is the tool most people look first to curb inflation. Higher borrowing costs will not bring food prices down. That is not to say that interest rates should not be raised - for example, higher rates would encourage companies to make more considered investment decisions, increasing the efficiency with which loans are made. But one should not expect higher interest rates to make much of a difference to inflation.

The government floated a more promising idea a week before, suggesting that the level of subsidies to low-income households be linked to the rate of inflation. One may question whether allowing households to increase spending when inflation is rising would not just push prices higher. But that should not be a concern because now inflation is being primarily driven by problems with supply rather than overheating demand.

Surveys and sales figures show that households have reined in real spending as inflation has risen over the last few months. Consumer confidence is at an all-time low, which is hardly a sign of exuberant demand. So inflation-linked subsidies could help people struggling the most to cope with rising prices (and given the strength of the government budget, these are something the government can easily afford).

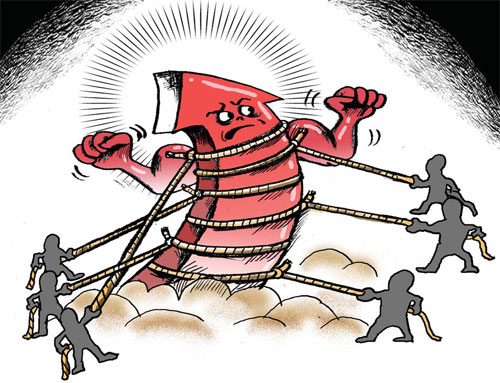

A proper-level currency revaluation would help, too, by making imported commodities cheaper. More generally, though, the problem lies in the skewed pattern of China's economic growth. Over the past decade, the wealthiest families have seen the strongest income gains. A disproportionate share of China's income is paid out as profits rather than wages, to the benefit of company owners and stock market investors rather than ordinary workers. Those at the bottom of the income distribution table have been left behind.

The 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2016) is built around a call to shift toward more domestically driven growth, supported by mass consumption and strong income growth. That change cannot come too soon.

The author is a senior China economist at Capital Economics, a London-based independent macroeconomic research consultancy.

E-paper

Sindberg leaves lasting legacy

China commemorates Danish hero's courage during Nanjing Massacres.

Preview of the coming issue

Crystal Clear

No more tears

Specials

NPC & CPPCC sessions

Lawmakers and political advisers gather in Beijing to discuss major issues.

Sentimental journey

Prince William and Kate Middleton returned to the place where they met and fell in love.

Rent your own island

Zhejiang Province charts plans to lease coastal islands for private investments