Reverse engineering

Updated: 2011-03-04 10:46

By Andrew Moody (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|

Ole Scheeren, the architect behind the CCTV tower (background), |

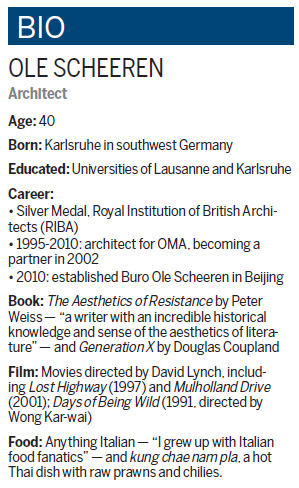

Leading German architect believes next stage is to project Chinese experience to Europe

German architect Ole Scheeren fervently disagrees with critics who dismiss much of the architecture in Beijing as being drab and of poor quality.

The view among many international architects is that a few modern landmark buildings do not make up for the mass of crumbling concrete estate, which ought perhaps to face an appointment with a bulldozer.

"I have a real weak spot for all the 1970s and 1980s buildings in this city, which I think have a beautiful kind of calmness, if not honesty, about them," he says.

It is a stance you would not necessarily expect Scheeren to take since he was the lead designer of not just a landmark building in the city but also probably the landmark building in the country.

|

The CCTV tower, completed in 2009 at a cost of 1 billion euros in the Central Business District (CBD), is among the strangest looking buildings anywhere in the world, consisting of two leaning towers that are connected at the top.

"I think it is important a city consists not only of a few so-called landmark buildings but also a generic mass and substance. I think it is incredibly important to the health of the city that you don't have to pay attention to everything," he says.

Scheeren, himself, has an unassuming sort of calm, like the older residential and commercial buildings he admires.

Our interview is in the offices of Buro Ole Scheeren, the new architecture practice he launched last year, in the trendy retail and commercial area complex of Jianwai SOHO.

He designed the CCTV tower while at the Dutch architecture firm OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture) but decided to branch out on his own.

The firm has one other partner, Eric Chang, an American architect who headed OMA's Beijing office, and employs 25.

Scheeren relocated to China seven years ago and he says having an architecture firm based in Beijing is a conscious move and could prove a platform from which to do European projects as well.

"Architecture used to be all about working from the West for the East. Then it was about going to the East to work for the East. The next stage for me is to project back the experience we have gained here and see what could happen in Europe if we could apply our knowledge from here," he says.

He believes what is happening in China architecturally could have an influence on projects across the world.

"There is obviously something of a reversal happening. Europe and America used to represent the progressive world but I think that is clearly shifting. There are many projects in which this country has taken quantum leaps in projects and the CCTV tower is only one of those," he says.

Some say many of the modern projects in China have nothing in common with traditional Chinese architecture such as the Forbidden City in the center of Beijing.

"Up to the early 1990s there was a referential system, where you would see a 30-story building with a Chinese-style roof on top. They are still around and they are sort of a Chinese post-modern," he says.

"I think, however, it was relatively soon realized that this was perhaps not a true sense of Chinese identity."

Scheeren, however, does not want to be specific about what does represent Chinese modernity in terms of architecture.

"I think there is still an open question and the answer is by no means final at this stage. I think an element of it is dedicated to progress and a future which surpasses the limits and boundaries of an entirely risk averse Western culture," he says.

Scheeren comes from a firmly European culture, however, and was brought up the son of an architect in Karlsruhe in southwest Germany.

This meant as a teenager he found himself on construction sites and working with models in his father's office.

Being the son of an architect made him question whether he should follow the same career.

"It certainly generated a moment when I thought I would never be an architect. I was fairly convinced I would do something else for a while. I think in a way I knew too much about the job," he says.

He says he had a "non-linear training" switching from formal education at the universities of Karlsruhe and Lausanne in Switzerland to bits of work experience.

"For a certain period I considered not even getting my degree. I remember applying for a scholarship in Germany and the committee looking at my CV and saying this makes absolutely no sense," he says.

It was during this period of relative drift he got his first experience of China when he went traveling for three months in his early 20s.

"I just wanted to go to the place in the world I knew the least about. I just went off into the middle of nowhere. I learned a whole lot about life and how things were not quite as I was taught in my European upbringing," he says.

He joined the Dutch firm OMA in 1995 and in 2002 became a partner and responsible for the firm's Asia work.

The CCTV tower came out of the Chinese government wanting innovative architecture as part of the design of the new CBD.

"Beijing had won the Olympics and there was a clear quest for what the future of this part of the world could look like," he recalls.

The design, which is seen as anti-skyscraper in that it is like a skyscraper bending over on itself, was informed by a number of influences.

"We took the whole skyscraper concept and bent it back on itself and created this technical metaphor of a circuit. Once the piece emerged it suddenly had a power in itself and there was this moment we looked at each other and said, 'This is it'."

Despite its odd external shape, all the floorplates within the building are perfectly rectangular. Only the facade slopes by six degrees which inside is barely noticeable.

Scheeren's firm is now working on an eclectic mix of projects including a tower in Kuala Lumpur, a 2,000-seat theater as well as a small-scale studio for an artist, both in Beijing.

Scheeren is keen to continue his work in Beijing, a sprawling city with a relatively low density of buildings.

"Beijing is a very specific and special city. It is very hard to find anywhere remotely like Beijing. It has many parts and it is about the people who inhabit it," he says.

But if the city becomes the capital of the largest economy in the world, how will it look in, say, 2050?

"We will see. Certainly some areas of the city will densify significantly. I think the CBD is still on its way. The city is not very constrained in that there is space around it and it is already starting to generate its own suburbia. Whatever the future, I hope to play a part in that happening."

E-paper

Pearl paradise

Dreams of a 'crazy' man turned out to be a real pearler for city

Literary beacon

Venice of china

Up to the mark

Specials

Power of profit

Western companies can learn from management practices of firms in emerging economies

Foreign-friendly skies

About a year ago, 48-year-old Roy Weinberg gave up his job with US Airways, moved to Shanghai and became a captain for China's Spring Airlines.

Plows, tough guys and real men

在这个时代,怎样才"够男人"? On the character "Man"