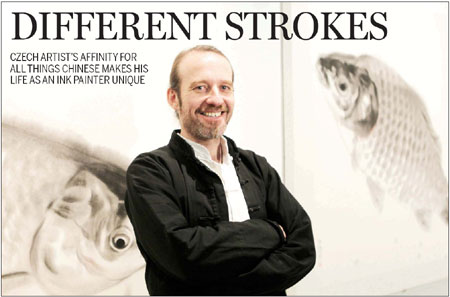

Different strokes

Updated: 2011-02-11 10:59

By Zhu Linyong (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|

Jiri Straka first came to China in 1991 to initially learn the |

Czech Artist's affinity for all things Chinese makes his life as an ink painter unique

Czech Sinologist and artist Jiri Straka says he has a "natural-born affinity with anything Chinese". But the 44-year-old has gone much further than simply being an aficionado of Chinese culture. Rather, he is "living the Chinese way? Always wearing traditional Chinese clothing and a pair of cloth shoes, the 44-year-old cuts an eye-catching figure.

Jaws dropped in 2002 during the 2nd Shenzhen international ink-art biennale, when the blue-eyed, long-haired artist grabbed a Chinese paint brush, dipped it into an inkpot, and worked barefoot on a broad sheet of rice paper on the ground.

Since 2000, Straka has done such live "performances" of ink painting at a Buddhist temple in Jilin province, on a sand beach in Guangdong province, and on the open ground just meters away from the Czech pavilion at the Shanghai Expo.

Eyebrows are also raised when people see this European man skillfully rub shoulders with local friends, from urban centers like Beijing and Shanghai to the small, remote town of Guiping in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region.

His most recent show, The Mundane World at Beijing's Today Art Museum, was his first solo exhibition of ink paintings in China. Straka was apparently comfortable with all the formalities, saying hello in the Chinese way to coming and going guests, toasting with baijiu (white liquor), and speaking fluent Mandarin with a slight Beijing accent.

Straka is settling down in the Chinese capital, which is quickly becoming an international metropolis, though he still spends part of each year in Prague.

"I've traveled and lived in a couple of Chinese cities over the decade," he says. "Beijing is my favorite."

Although he hates its polluted air and traffic congestion, Straka owns a house and rents a spacious factory-turned studio in the eastern suburbs of Beijing, living with his wife, Qin Kunying, a Han Chinese painter from the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, and their 9-year-old son.

Straka and Qin are busy building a Czech Chinese Art Center, covering a floor space of 2,000 square meters at Songzhuang, the country's major stronghold for bohemian artists.

Soon to open, the center "may serve as a cultural-exchange platform" with warm support from the Czech Embassy and artists back home according to Straka, adding: "I am becoming part of the fast-changing life of Beijing."

It has not been a hard decision to make but just something that came quite naturally, says the artist.

"I developed a strong love for Chinese art and culture as a little boy, but I cannot explain why," he says.

Born into a working-class family in Prague, Straka collected all things Chinese - a matchbox, sweet wrappers and tiny handicrafts imported from China in the 1970s. China loomed large in his imagination during his school years when he was an art major in print-making.

He first set foot on Chinese soil in 1991, coming for several months with other Czech students to learn some Chinese at Beijing Language and Culture University.

By then, Straka had been practicing Chinese ink painting for years. It all started after he was absorbed by a colorful catalog of paintings by master painter Qi Baishi from his father's bookshelf.

He attempted to copy works by the old masters at that time.

"It was merely for fun You cannot call the paintings by a teenager real art," says Straka, who received training at institutions such as the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing in both Chinese ink painting and Chinese painting restoration and conservation in the 1990s.

However, Straka's family and friends in Europe questioned his choice of ink painting as a prime medium for artistic creation.

They told him it was "ridiculous to waste time in a well-developed, old Oriental art" and suggested he should take up oil painting.

But Straka did not give up the medium. Instead, he began participating in major events in the field of ink art in Shenzhen, Shanghai, Beijing and Taipei.

His art changes constantly as he draws inspiration from his experiences around China.

His early ink art was about figures, similar to those found in ancient masterpieces.

But soon, bored by traditional subjects, he moved to paint poetic depictions of natural things such as trees, flowers, and the bamboo groves of southern China.

Six years ago, he began painting works with a philosophical touch after he was struck by the scene of piles of slaughtered animals at an open-air market in rural Guangxi. And his conversion to Tibetan Buddhism in recent years adds yet another dimension to his art.

In his meticulously crafted works - usually larger-than-life images, such as a blood-stained mosquito, a trembling dog, a predatory bird and its dying prey, a fish out of water - "one can sense an ironic detachment", says critic Hang Chunxiao.

"I mean to raise issues a bit remote from our daily living, such as the momentary and the eternal, and life and death", explains Straka.

The Czech artist acknowledges he is good at depicting motifs such animals, birds and insects in a symbolic manner.

His current challenge is in "struggling to find the right way to portray contemporary figures" with the so-called mogu huafa (boneless painting method), a thousand-year-old painting tradition that does not use resilient lines and forceful strokes like calligraphers do.

Still, Straka believes he can find a position as an ink artist in China.

"Straka has pushed the boundaries of Chinese ink art his ink art is not confined to the periphery of classic Chinese art but is a vanguard, conceptual art," points out Wu Hongliang, critic and curator for Straka's Beijing solo show.

The emergence of ink artists with international backgrounds such as Straka is an important phenomenon on the contemporary Chinese art scene, according to Wu.

"When looking into the future of Chinese ink art, we cannot ignore this unique type, created by foreign artists. They offer new directions to the century-old issue of bridging Western and Chinese art", says Wu.

E-paper

Pearl paradise

Dreams of a 'crazy' man turned out to be a real pearler for city

Literary beacon

Venice of china

Up to the mark

Specials

Power of profit

Western companies can learn from management practices of firms in emerging economies

Foreign-friendly skies

About a year ago, 48-year-old Roy Weinberg gave up his job with US Airways, moved to Shanghai and became a captain for China's Spring Airlines.

Plows, tough guys and real men

在这个时代,怎样才"够男人"? On the character "Man"