Captured in charcoal

Updated: 2014-08-12 09:43

By Raymond Zhou and Huang Yiming(China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Making traditional portraits is not only a family business, it symbolizes a way of life for old Haikou. Han Cuiqiong is determined to stop it from slipping away in the rush toward modernity, as Raymond Zhou and Huang Yiming find out in Haikou.

In an age when photographs can be taken and zapped around the world in an instant, it seems antiquated to spend hours or days polishing a portrait.

But Han Cuiqiong, 60, never wavers in her evaluation of the unique art form known as charcoal sketching. She has spent 40 years honing it.

When the local government of Haikou, capital city of Hainan province, restored the old commercial hub of Zhongshan Road and turned it into a pedestrian-only street with boutiques and cafes but kept the old signage intact on the walls, it invited Han to move in. As an enticement, it waived her rent.

Han's presence adds a touch of local color. In the old days before photography became popular, people relied on charcoal sketching for portraits of family members, especially those who passed away. In the mid-1980s, there were as many as two dozen charcoal painters in this neighborhood. "We could produce 30 or 40 portraits a month," she recalls. "But nowadays it has dwindled to just a few."

Unlike Western sketch artists active in tourist hotspots, the kind of charcoal art Han specializes in does not require the object to sit for the session. "We generally rely on photos," she explains. And it takes two or three days to finish one portrait, and much longer if the client requires color instead of the usual black and white.

Sometimes, not even a photo is available as a reference. Han once had a customer from Taiwan who asked for a portrait of his mother, but all he could produce was a photograph of one of his maternal uncles. He described to Han the similarities and differences between the two, and she eventually sketched a charcoal portrait to his satisfaction.

Things started to change during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) when demand for Mao Zedong's portraits skyrocketed. "We did a lot of Mao portraits back then," she says, and this skill of drawing the likeness of famous people rather than ordinary people's ancestors or aging parents has come in handy in recent years. Celebrity portraits, such as ones of Confucius and Michael Jordan, are now in vogue and sell more briskly than family portraiture, she reveals.

Han picked up the skill from her father when she was 16. Her father, Han Guanping, started by painting backdrops for local theatrical companies. "We lived in a 20-square-meter room and would help my dad by adding color to the backdrop he was working on, which would take up a whole wall," she says. "There was a lot of laughter."

The elder Han spent 60 years in the profession. Before his death in 2005, he had seen his grandson, Ye Baolong, taking up the family business. Ye learned it from his mother. To broaden his horizons, Han Cuiqiong made him master all kinds of painting styles, including oil painting. "He is a much better painter than I am," she admits, but in the firmament of cultural Haikou she is a fixture and people specifically ask for her to personally do a piece.

Ye comes in all the time to help his mother, but makes money from selling mobile phones. "My mom can support herself by selling portraits and tourism souvenirs," he says. "But once the rent kicks in, there is no way we can sustain the business." The rent is rumored to be around 8,000 yuan ($1,290) a month by market value, much higher than the revenue trickling in.

"We know how difficult it is for a small business like Han's to survive. She will text me when she makes a good sale," says Zhao Aihua, deputy director of the organization responsible for preserving historical Haikou and waiving her rent. "Culture is not just about buildings, it is about the lifestyle. We choose to help Han because what she does represents a piece of local culture that will quickly evaporate if left to market forces."

Although barely 8 square meters in size, Han's storefront has attracted more than its fair share of attention and has taken on many functions that people hadn't anticipated. Other artists have come and asked her to display their works. It has become a gallery as well. There are scrolls of calligraphy and even one oil painting that add a modern twist.

When business was slow, Han coached her granddaughter in writing and drawing. It did not take long for other parents to ask her to teach their kids. The covered walkway on the historical street has thus turned into both a demonstration room and a classroom where children can pick up drawing and painting skills from an old master.

Han's store also functions as a club, attracting other artists and kindred spirits. But you don't have to be physically there to talk art and craft with her. She uses her iPhone to share her work and her ideas of charcoal sketching with friends who may live far beyond the island. "Oh, that's nothing," she says when asked about her dexterity with the new gadget. "I learned to draw on my cellphone many years ago."

Occasionally, Han laments that she did not learn other styles of painting, which could "fetch 10,000 yuan apiece", she says. But she is not bothered by the high efficiency of photography, not any more. "Have you noticed how fast photo portraits fade? Our charcoal paintings do not fade."

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn

|

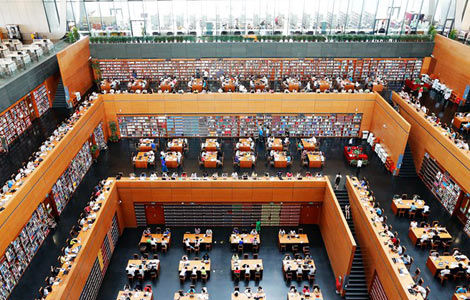

Young students learn charcoal art from Han Cuiqiong at her workshop in Haikou, Hainan province. Photos by Huang Yiming / China Daily |

|

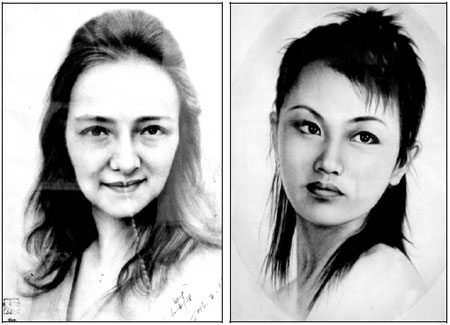

Charcoal portraits by Ye Baolong, Han Cuiqiong's son. Making charcoal paintings has been Han's family business for three generations. |

(China Daily 08/12/2014 page20)

Today's Top News

NATO to offer tailored support to Ukraine

Babies bob about in water at US's first baby spa

News website staff face extortion probe

China's meeting on 13th five-yr plan

Number of visitors to China drops

Export of mooncakes on the rise

Putin outlines ceasefire plan for Ukraine crisis

China paves way for sports investors

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|