Keepin' it clean

Updated: 2014-06-04 07:00

By Mei Jia (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Pornography is illegal in China, a rule that extends to erotic literature, and e-publishers have to work hard to stay ahead of the booming underground market in provocative writing. Mei Jia reports.

E-publishing has meant new content is available on a daily basis for ferocious readers, but for Web-lit editors like Li Xiaoliang, the rapid pace of publishing means he must check hundreds of e-books a day to ensure they are free of "pornography" and other illegal content.

Li and his colleagues are assisted by computer programs to scan the books, but they still need to add new words or new combinations of words into the system every day to stay ahead of the porn writers.

It can be a fine line between art and porn, and the Chinese language includes many clever puns to make that line even trickier to detect. Li, who worked under the name Hu Shuo for Chuangshi Literature under Tencent Inc, believes he has refined his skills in detecting inappropriate online content over 10 years of experience.

"To us, content that violates Chinese laws and regulations and harms public moral values should be banned on our website," Li says. "In some complicated cases, all editors need to have a discussion to decide (what is inappropriate).

"But we know that generally, historical novels and hardcore sci-fi is safer than urban white-collar love stories. Because as writers develop their stories into a series, they have less potential to be porn than, say, stories featuring a male protagonist with a skill that helps him to attract almost every woman he meets."

Online literature boasted 274 million readers by the end of 2013, according to the latest report by the China Internet Network Information Center. More than 2 million registered writers upload millions of stories every day, the report says.

But there are concerns about widespread pornographic content in online literature, which can be accessed by children. Yang Chang, a judge of juvenile crime in a Beijing court, told China Central Television of a case in which four teenage boys raped a girl after reading porn online.

"Thirty years ago, literature editors had it much easier. The editors all knew that literary descriptions of the human body should stop at the parts above the chest, and descriptions of intimacy should go no further than kissing," according to veteran editor Liu Feng with Nanjing-based Yilin Press.

But ideas about what is and is not acceptable changed as Chinese society opened up and developed, adding to the difficulty in deciding what should and should not be allowed to be printed.

Though both Anquan.org and Chuangshi Literature have developed computer programs to help scrutinize information, inappropriate content will always find a way around the system.

A year ago, Anquan.org, an independent third-party website dedicated to safeguarding the Web environment, advertised for a Chief Web Porn Identification Officer, offering an annual salary of 200,000 yuan ($32,020).

The job hit news headlines thanks to one of the interview questions, in which the applicants were asked to analyze a sentence full of puns and sexual innuendoes.

"We're looking for someone who is familiar with not only the Chinese legal rules on pornography but also with internet companies' common practices in China and abroad," says Zhang Yi, director of marketing with Anquan.org.

They hope the chief officer will help establish standards for porn identification, and instruct their 2,000 identification officers who are zealous netizens who have volunteered to protect Internet safety, Zhang says. "But the post is still vacant. We haven't found someone who fits the bill."

However, to online writers, the line between pornography and art is simple.

Yang Hao, a Qingdao-based writer whose pen name is Sanjie Dashi, has attracted more than 100 million clicks to his humorous and history-based online stories.

"The writers' intention in creation tells us everything," Yang says.

"If something is written to arouse sexual interest, it's porn. If is written for fun, for simple pleasure and enjoyment, it's art."

Yang says that more Web porn in the form of online literature has surfaced over the past two years. "The industry is getting bigger and some covet the profit," he says.

"They don't love literature. They take shortcuts by writing porn just to earn money," he says.

Obscene literature sometimes gets 100 million clicks very quickly, he says.

With an overall annual income of 4 billion yuan, online literature has become a big business in a little more than a decade of development, the CNNIC report says.

Wide usage of smartphones and portable e-readers has spurred the boom, says an official surnamed Wang with the information section of the National Office Against Pornographic and Illegal Publications.

Wang adds that the office has strengthened its attacks against porn in cyberspace since 2009.

Most of the major online literature websites are able to apply a series of mechanisms to check pornographic and illegal content, "which is the basis and premise of our job", says Wu Wenhui, CEO of Tencent Literature.

The office launched an anti-porn movement called "Cleaning the Web 2014" from April to November to weed out the illegal content and keep them away from the reach of children, Wang says.

The Chinese-language Internet portal Sina.com was fined for having 20 books of lewd and pornographic online literature, which earned them 500,000 yuan of illegal income, the office announced.

Contact the writer at meijia@chinadaily.com.cn

Jin Haixing, Zou Ren and Wang Qiang contributed to this story.

'LIT PORN' IS BIG PROBLEM ONLINE

In China, pornography is illegal both online and offline. The penalties vary according to the level of offense, says Wang, an official at the National Office Against Pornographic and Illegal Publications, who declined to give his full name.

As part of a crackdown on cyber pornography, the government launched "Cleaning the Web 2014" campaign in April. Since then it received more than 30,000 complaints, according to Wang, who works in the information section of the department.

"The Interests of the underage consumers is well considered here," Wang tells China Daily of the focus on protecting children.

The office, with 27 members from other ministries, is set at the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television. An arm of the administration identifies pornographic material online and in print.

"Actually it is easy to detect porn because that's the information free of any artistic or scientific value," Wang says. "Average readers can do that."

The officials tasked with identifying such material need to classify it, too, because the most serious violations are taken as cases in criminal courts, while lighter offenses attract administrative punishments.

The identification is mainly based on Article 367 of the Chinese Criminal Law and two of its interpretations by the Supreme People's Court and Supreme People's Procuratorate respectively in 2004 and 2010, as well as the Regulation Identifying Lewd and Pornographic Publications by the SAPPRFT.

There are detailed rules, including those that involve sex with children or of the same sex, sexual violence and other depictions that a common reader or viewer may find disturbing. The office is open to offense reporting 24 hours a day and is present on the social media platform WeChat.

Pornographic content, among Web literature, accounts for a small portion online when compared to videos and other such elements. There could be 10 books in a hundred that are offensive, he says. But mostly underage people read literature on the Web, and online "lit porn" easily gets millions of hits, Wang adds.

Li Xiaoliang, veteran web editor of Chuangshi Literature under Tencent, says their readers are aged between 16 and 40. "The majority of the readers love to read fantasy that fulfills their dreams, but not the sexual content," Li says.

Readers have their own standards by which they judge books. Many love books with good plots and positive values, according to Wu Wenhui, CEO of Tencent Literature.

|

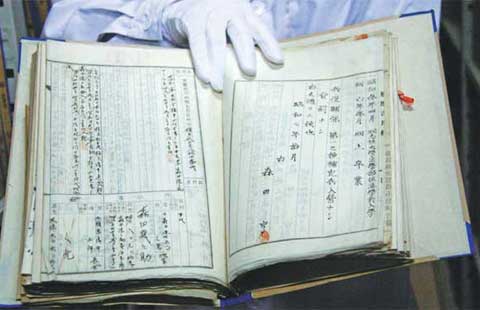

Wang Xiaoying / China Daily |

(China Daily 06/04/2014 page19)

Today's Top News

Brazil installs Chinese security systems for Cup

Spain's king abdicates to revive monarchy

FIFA probe into Qatar 2022 to report

Beijing to ease green card rules

Apps shine at Apple's WWDC

Brazil's goal is more than soccer

Abe, Hagel's accusations rejected

Yuan clearing bank to open in UK

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|