Peeking through time

Updated: 2014-02-27 07:31

By Deng Zhangyu in Jingzhou, Hubei (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

When a more than 2,100-year-old corpse was unearthed from a tomb in Jingzhou, Hubei province, his skin was moist and flexible. All his limbs could move. His blood vessels were clear to see as if he had only just died.

This well-preserved male corpse discovered in 1975 is now one of the most important features in the collection of the Jingzhou Museum, whose researchers were involved in the excavation.

According to a wooden tablet found in the tomb, he died in 167 BC at age 60. A jade seal found in his mouth indicated his name was "Sui".

Sui was a government official, equivalent to today's deputy mayor. He suffered numerous illnesses when he was alive. Sui was found inside the smallest of three coffins, each inside the other. Wooden figurines representing servants and horses and brown coins were also found in his tomb.

After being buried deep under the ground for two millennia, Sui's clothes, hair and nails had turned to dust, but his 32 teeth still remained white and strong.

Sui's body is considered better preserved than Lady Dai, a well-known female body found in 1971 at Changsha's Mawangdui, a Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) tomb found in the adjacent Hunan province. The discovery attracted worldwide attention. But why the ancient corpse was so well preserved is still a mystery.

In some experts' opinion, its preservation can be partly attributed to some accidental factors. When Sui's coffin was opened, reddish fluid flowed out. Studies found the liquid was a mix of herbs, cinnabar and water.

"The underground water level is high in Jingzhou. Year after year, water penetrated Sui's coffin and produced this magic fluid," says Wang Mingqin, director of Jingzhou Museum.

The liquid mix of water with herbs buried with the body, also found in Lady Dai's tomb, is thought to be a possible natural embalming fluid, which would explain the incredible preservation of Sui's body. The tomb next to Sui's was his wife's. But nothing was left there except for some remains of her clothes.

Sui's body attracts lots of visitors to the museum every year. Even during the Spring Festival, there are more than 1,000 visitors every day, many of whom are from outside Hubei, says Peng Hao, deputy director of the museum.

But the museum boasts much more than Sui's remains - it is also home to many treasures unearthed from countless tombs buried under the city, a stronghold in the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC) to the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220).

"Jingzhou is an ancient city famous for the culture of the powerful Chu Kingdom during the Spring and Autumn Period. The silk and wooden lacquer ware in our museum shows the wisdom of the Chu people, "says Wang.

One significant part of the collection is the silk found in a tomb from the Warring States Period (475-221 BC). In terms of variety and preservation, the silk found in the Mashan No 1 tomb gave people a big surprise.

According to workers who were on the spot in 1982 when the tomb was opened, the red and white colors on wooden figurines' faces were so vivid that they looked like they had just finished their makeup hours ago. However, they quickly started to rot once the tomb was opened.

Inside the tomb was a female corpse who was wrapped up by 35 layers of silk. Each layer was a different type of silk. Although the female corpse had decayed, the silk fabric was intact and bright in color. People call it an underground treasure house of silk.

The lightest and thinnest is a piece of gauze silk called luo. The patterns on the gauze were phoenixes and tigers. The skill to produce that kind of gauze is perhaps lost now, making the piece the only one of its kind.

Besides the silk and the corpse, the museum also has a notable collection of wooden lacquer ware. The collection accounts for 60 percent of all the wooden lacquer ware of the Chu Kingdom and Han Dynasty.

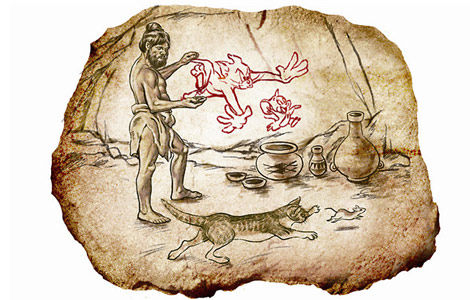

The most commonly found type of lacquer ware is a drum with two phoenixes standing on tigers. The phoenix is an emblem of the Chu people and can be found on many objects. Tigers are thought of as the king of nature as well as an emblem of their area.

Chu people had the phoenixes stand on the back of tigers to show that they were more powerful than nature and their enemy country, says Tao Ya, the museum's academic guide.

Usually, phoenixes have a pair of antlers on their backs. Milu deer were found in large numbers in this area at the time, and antlers were a metaphor for holiness, says Tao.

All these wooden objects were found in tombs buried deep under the soil. Their shapes were unique and they were exquisitely made. They were also symbols of the tomb occupants' social status: feudal nobles.

Unlike those found in other parts of China, which were mainly made of bronze, the relics in Jingzhou were made of wood to protect themselves from the high level of humidity in the area. That's also why so much wooden lacquer ware was so well preserved.

dengzhangyu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 02/27/2014 page22)

Today's Top News

Ukraine disbands riot police unit

Putin puts troops in W.Russia on alert in drill

Construction of China-Russia railway bridge starts

Turks stage protests demand PM's resignation

Forecast:China to lower growth rate

Italian new govt wins vote of confidence

Ukraine enters uncharted water

Li urges stronger S. China Sea ties

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|